![]()

1

Language

I HAVE A FRIEND who says that studying the psychology of language is a waste of time. He expounds this idea very eloquently and at great length. He says it in nice, beautifully enunciated – if rather loud – sentences to anyone who will listen (and often to people who won’t). I think this irony is wasted on him.

One of his reasons for his belief is that he thinks there’s nothing special about language. We learn language as we learn any other skill: we learn to speak like we might learn to ride a bike. It makes use of the same psychological resources and processes as everything else we do. For him there’s no difference between speaking a sentence and navigating our way home.

I think he wants things both ways, because when I put the alternative to him – that there is something special about language, that maybe we don’t learn it like we learn other things, and maybe it doesn’t use the same psychological processes as everything else – he says that in that case it’s just a special case, and therefore not very interesting either.

Using language is one of the most impressive things we do. I find only vision comes close. We routinely produce utterances of amazing complexity and originality. Think back to the last few things you’ve said; have you ever said exactly those things before? Probably not, and probably no one else has either (although I am assuming you haven’t just said “hello”). Our use of language is creative. We combine words and sentence structures in novel ways all the time, and we make these combinations incredibly quickly and with amazing accuracy. We can do this combination in speech or writing. We can also decode what other people say – we listen and read, and extract the meaning and intended message, again apparently effortlessly. All this combining and decoding is for a purpose: communication. It enables me to have a thought and ensure that you have exactly the same thought.

Language is also important. We spend a lot of time using it or even just thinking in it. Most of us have a running voice in the head telling us what to do and what we’re thinking, and it’s easy to think of that voice as being the core of our being. The complexity of modern life is unthinkable without language: how could we have designed and built cars, computers, and atom smashers without it? How could we maintain such close, personal relationships without it? Indeed, it’s difficult to imagine being human without language.

Perhaps unwittingly, my conversations with my friend touch upon three of the most interesting issues in the modern study of language. First, how do we actually do language? What are the processes involved in speaking, writing, listening, and reading? Second, how do children acquire language? They’re not born talking, but they soon are chattering away, if not at first quite like adults. Third, to what extent does acquiring and using language depend on knowledge and mechanisms specific to language?

This book is about the psychology of language. I find the “psychology of language” to be a bit of a mouthful, and what on earth do you call people who do it? Psychologists of language? In the sixties and seventies there was a perfectly good word, “psycholinguistics”, with the people who did psycholinguistics called psycholinguists. For reasons I’ve never understood these words became unfashionable about the same time as flares stopped being widely available. I don’t think these events were linked, but perhaps if “psycholinguistics” can be brought back into fashion, even flares stand a chance again.

“Psycholinguistics” and “psycholinguists”: I’m going to use these words. Perhaps they will be deservedly revived. Perhaps I’ll have started a fashion.

■ What is language?

Type “language definition” in to your favourite search engine. Here’s one I’ve adapted from www.thefreedictionary.com, according to which language is

- the communication of thoughts and feelings through a system of arbitrary signs such as voice sounds or gestures

- such a system including its rules for combining its components such as words

- such a system as used by a nation or people.

This definition covers the most important aspects of what language is, but it’s worth considering these points in more detail.

First, language is primarily a system for communication: its main purpose is to transfer information from one person to another. I think I’d add to this point that the communication is intended. Animals communicate to each other – for example a blackbird singing communicates that a male is resident in a territory and available to females – but it’s far from obvious that there is always a deliberate intention to convey that information. In contrast, when we talk, we intend to convey specific information. This is not to say that everything we communicate is intentional: I might say something foolish and thereby communicate my ignorance, but this is a side effect of what I say rather than its main effect, and certainly language didn’t arise to convey side effects. It is also not to say that the only function of language is strictly intentional communication: we often use language for social bonding, as a means of emotional expression (“darnation!”, and sometimes perhaps a little stronger), and even for play (telling puns and jokes). And language seems to play a central role in guiding and perhaps even determining our thoughts.

Second, language is a system of words and rules for combining them. Words mean something; they are signs that stand for something. “Cat”, “chase”, “rat”, “truth”, “kick”, and “big” all refer to objects in the world, events, ideas, actions, or properties of things. We know thousands of words: we know their meanings, and what they look and sound like. All this knowledge is stored in a huge mental dictionary we call the lexicon. But language is clearly much more than a list of words; we combine words together to form sentences, and sentences convey complex meanings about the relation between things: essentially, who did what to whom. But we don’t just combine words in any old fashion; like computer languages, we can combine words only in particular ways. We can say “the cat chases the rat” or “the rat chases the cat,” but not “the cat rat the chases” or “the the chases cat rat”. That is we know some rules that enable us to combine words together in particular ways. We call these rules the syntactic rules (sometimes just the syntax) of the language. What is more, word order is vitally important (in languages such as English at least): “the cat chases the rat” means something different from “the rat chases the cat.” It is our ability to use rules to combine words that gives language its immense power, and that enables us to convey a huge (infinite, in fact) number of ideas.

The distinction between the lexicon and syntax is an important one in psycholinguistics. If syntax makes you think of grammar, you’re right: we use the word grammar in a more general way to describe the complete set of rules that describe a language, primarily the syntax, how words can be made up, and even what sorts of sounds are permitted and how they are combined in a particular language. Be warned, though, that “grammar” is unfortunately one of those words that can mean what we want it to mean; sometimes it’s used almost synonymously with “syntax”, sometimes as the more general term to refer to the complete set of rules for a language. No wonder psycholinguistics is hard.

Third, the relation between the meaning and appearance or sound of words is arbitrary: you can’t tell what a word means just by hearing it; you have to know it. Of course there are a few words that sound rather like what they depict (such words are called onomatopoeic) – but there are just a few, and even then the meaning isn’t completely predictable. “Whisper” sounds a bit like the sound of whispering, but perhaps “sisper” would have done just as well. Knowing how “hermeneutical” is pronounced tells you nothing about what it means.

Fourth, although we have defined language in the abstract, there are many specific languages in the world. We say that English, French, Russian, and Igbo (a Nigerian language) are all different languages, but they are nevertheless all types of language: they all use words and syntactic rules to form messages.

■ How do languages differ?

A motif of this book is how bad I am at language and languages. I’m not proud of this fact; it’s just the way it is. Indeed, I think I should have your sympathy for reasons that will become apparent later. It’s perhaps odd that someone so bad at language should carry out research into language, but perhaps there’s something in the adage about psychologists really just being interested in their own particular problems. Being hopeless at foreign (to me) languages, I had to ask members of my linguistically diverse psychology department how they would say the following in their own languages (I could manage the first):

The cat on the mat chased the giant rat. (English)

Le chat qui était sur le tapis a couru après le rat géant. (French)

Die Katze auf der Matte jagte die gigantische Ratte. (German)

Il gatto sullo stoino inseguiva il topo gigante. (Italian)

De kat op de mat joeg op de gigantische rat. (Dutch)

Pisica de pe pres a sarit la sobolanul gigantic. (Romanian)

Kot ktȯry był na macie, gonił ogromnego szczura. (Polish)

A macska a szőnyegen kergette az óriás patkányt. (Hungarian) Matto-no ue-no neko-ga ookina nezumi-o oikaketa. (Japanese)

I think I know what’s going on in the French, Dutch, and German translations. It is fairly obvious that there are similarities between them and English, and I remember enough school French to be able to work out the rest. Italian looks a bit more different to me but is still recognisable. Polish, Hungarian, and Japanese are very different and unrecognisable to me; for all I know, my colleagues could be pulling my leg and causing me to write unwitting obscenities. I apologise if they have.

There are differences other than just the vocabulary (“cat”, “chat”, and “Katze” all mean the same thing). In German what is called the case of the noun and the form of the verb are much more important than in English; the form of nouns and verbs changes by a process called inflection to reflect their grammatical role – for example whether something is the subject or the object of the sentence – the thing doing the action or the thing having the action done to it. (There are other cases: I still remember nominative, accusative, vocative, genitive, and dative from my Latin lessons.) We do this a bit in English, when for example we use “she” as the subject of the sentence and “her” as the object, but nowhere near as much as in heavily inflected languages, of which German is one. If you know any Latin, you will realise that Latin is extremely heavily inflected, so much so that word order is relatively unimportant. To satisfy my nostalgia for being 12 again, here are the inflected cases of a Latin word, stella (“star”):

| stella – the star | stellae – the stars (nominative case) |

| stella – o star | stellae – o stars (vocative) |

| stellam – the star | stellas – the stars (accusative, for direct objects) |

| stellae – of the star | stellarum – of the stars (genitive) |

| stellae – to the star | stellis – to the stars (dative) |

| stella – from the star | stellis – from the stars (ablative) |

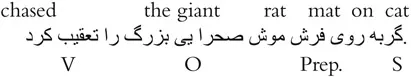

My Latin teacher made us learn these by repeating as quickly and as loudly as possible: stla, stla, stlam; stlae, stlae, stla – and the plurals. Japanese constructs its sentences very differently: I’m told the best translation is “mat on cat big rat chased”; notice how in Japanese also the verb comes at the end of the sentence. Turkish, like Finnish, Japanese, and Swahili, runs words modifying each other together, making it what is called an agglutinative language. Here is an example:

Ögretemediklerimizdenmisiniz? – Are you the one who we failed to teach?

(Where Ögret = to teach, emedik = failed, lerimiz = we, den = are you, misiniz = the one who). In agglutinative languages each unit in a word expresses a particular grammatical meaning in a very clear way.

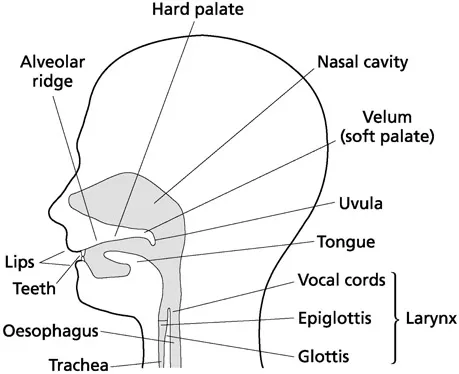

The sounds different languages use can differ, too. To an English speaker, the properly pronounced “ch” sound in the Scottish “loch” and German “Bach” sounds slightly odd; that’s because it’s not a sound used in “normal” English. Technically, it’s called a voiceless velar fricative because of the way it’s made and the vocal tract being constricted as air is pushed out through it, and English doesn’t use voiceless velar fricatives (see Figure 1.1 for a diagram of the articulatory apparatus). Arabic sounds different to English speakers because it makes use of pharyngeal sounds, where the root of the tongue is raised to the pharynx at the back of the mouth – and, of course, English sounds different to Arabic speakers because English doesn’t make use of pharyngeal sounds. Some African languages, such as Bantu and Khoisan, make use of loud click sounds as consonants. Japanese doesn’t make a distinction between the “l” and “r” sounds, which is why Japanese people learning English have difficulty in producing these sounds correctly. “L” and “r” are called liquid sounds; Irish Gaelic has ten liquids, and of course native English speakers would have difficulty learning all these distinctions. The list of differences in sounds between languages is clearly going to be enormous, and has obvious consequences for adult speakers trying to learn a new language.

Figure 1.1 The structure of the human vocal tract

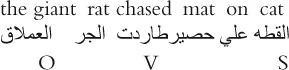

I also asked a colleague in Iran for a translation; here are the results in Farsi and Arabic, along with Greek, Japanese, and Chinese (ahead). These don’t even use the same script, or method of writing. What’s more Farsi, Arabic, and Hebrew are written from right to left.

Greek

Η γάτα στο χαλί κυνήγησε τον γιγάντιο αρουραίο.

Japanese

マットの上の猫が大きなネズミを追 いかけた。

Chinese

| 那只大老鼠 | 在毯子上 | 被 | 猫 | 追赶。 |

| (The giant rat) | (On the mat) | (Passive expression) | (The cat) | (Chased) |

Translation to Farsi

orbe(cat) rouye(on) farsh(mat) moush-e sahraie-ye(rat) bozorg(the giant) ra taghib kard(chased)

Translation to Arabic

Al-ghetta(cat) ala(on) hasir(mat) taradat(chased) Al-jerza al-amlagh(the giant rat)

Translation to Hebrew

תוקנאה הדלוחה ירחא ץדר חיטשה לא לותוחה

H′ chatul al h′ shatiach radaf acharey h′ chulda h′ anakit

So languages clearly differ in many ways: the words they use (the vocabulary), the preferred order of words, the syntactic rules they use, the extent to and way in which they inflect words to mark grammatical role, the way grammatical units are combined, the sounds they use, ...