- 468 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Public Policy Analysis, the most widely cited book on the subject, provides students with a comprehensive methodology of policy analysis. It starts from the premise that policy analysis is an applied social science discipline designed for solving practical problems facing public and nonprofit organizations. This thoroughly revised sixth edition contains a number of important updates:

- Each chapter includes an all-new "big ideas" case study in policy analysis to stimulate student interest in timely and important problems.

- The dedicated chapter on evidence-based policy and the role of field experiments has been thoroughly rewritten and expanded.

- New sections on important developments in the field have been added, including using scientific evidence in public policymaking, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and "big data."

- Data sets to apply analytical techniques are included online as IBM SPSS 23.0 files and are convertible to Excel, Stata, and R statistical software programs to suit a variety of course needs and teaching styles.

- All-new PowerPoint slides are included to make instructor preparation easier than ever before.

Designed to prepare students from a variety of academic backgrounds to conduct policy analysis on their own, without requiring a background in microeconomics, Public Policy Analysis, Sixth Edition helps students develop the practical skills needed to communicate findings through memos, position papers, and other forms of structured analytical writing. The text engages students by challenging them to critically analyze the arguments of policy practitioners as well as political scientists, economists, and political philosophers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Part

I

Methodology of Policy Analysis

Chapter

1

The Process of Policy Analysis

- Learning Objectives

- Introduction

- Methodology of Policy Inquiry

- Multidisciplinary Policy Analysis

- Forms of Policy Analysis

- The Practice of Policy Analysis

- Critical Thinking and Public Policy

- Chapter Summary

- Review Questions

- Demonstration Exercises

- Bibliography

- Case 1.1 The Goeller Scorecard and Technological Change

- Case 1.2 Using Influence Diagrams and Decision Trees to Structure Problems of Energy and Highway Safety Policy

- Case 1.3 Mapping International Security and Energy Crises

Learning Objectives

- Define and illustrate phases of policy analysis

- Distinguish four strategies of policy analysis

- Contrast reconstructed logic and logic-in-use

- Distinguish prospective and retrospective policy analysis

- Distinguish problem structuring and problem solving

- Describe the structure of a policy argument and its elements

- Understand the role of argument mapping in critical thinking

- Interpret scorecards, spreadsheets, influence diagrams, decision trees, and argument maps

Introduction

Methodology of Policy Inquiry

Multidisciplinary Policy Analysis

Policy-Relevant Knowledge

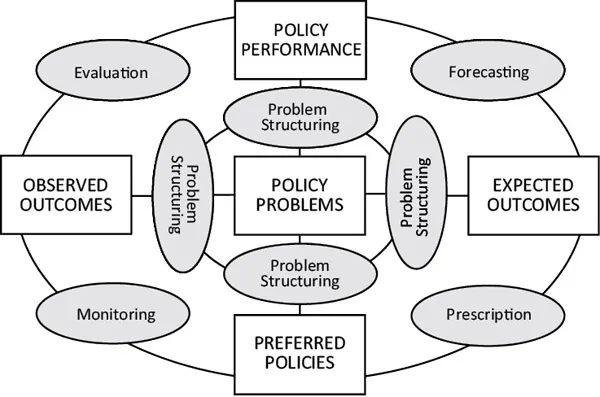

- Policy problems. What is the problem for which a potential solution is sought? Is global warming a man-made consequence of vehicle emissions, or a consequence of periodic fluctuations in the temperature of the atmosphere? What alternatives are available to mitigate global warming? What are the potential outcomes of these alternatives and what is their value or utility?

- Expected policy outcomes. What are the expected outcomes of policies designed to reduce future harmful emissions? Because periodic natural fluctuations are difficult if not impossible to control, what is the likelihood that emissions can be reduced by raising the price of gasoline and diesel fuel or requiring that aircraft use biofuels?

- Preferred policies. Which policies should be chosen, considering not only their expected outcomes in reducing harmful emissions, but the value of reduced emissions in terms of monetary costs and benefits? Should environmental justice be valued along with economic efficiency?

- Observed policy outcomes. What policy outcomes are observed, as distinguished from the outcomes expected before the adoption of a preferred policy? Did a preferred policy actually result in reduced emissions, or did decreases in world petroleum production and consequent increases in gasoline prices and reduced driving also reduce emissions?

- Policy performance. To what extent has policy performance been achieved, as defined by valued policy outcomes signaling the reduction of global warming through emissions controls? To what extent has the policy achieved other measures of policy performance, for example the reduction of costs of carbon emissions and global warming to future generations?

Multidisciplinary Policy Analysis

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Methodology of Policy Analysis

- Part II Methods of Policy Analysis

- Part III Methods of Policy Communication

- Appendix 1 Policy Issue Papers

- Appendix 2 Executive Summaries

- Appendix 3 Policy Memoranda

- Appendix 4 Planning Oral Briefings

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app