![]()

Chapter 1

Sports in Early America

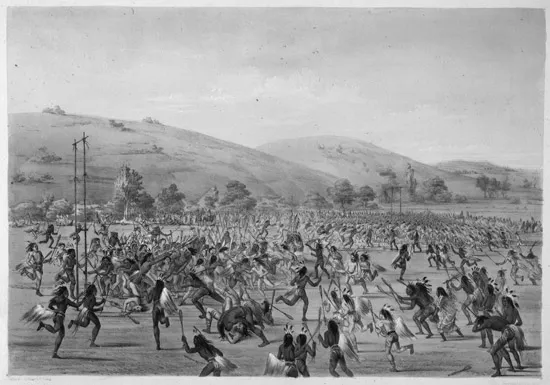

Choctaw athletes competing in a centuries-old Native American ball game, as depicted by artist George Catlin in the 1840s.

Learning Objectives

- 1.1 Discuss the different functions that sports served in Native American, European, and African cultures as well as the forces that shaped the sporting cultures that emerged in the early American Republic.

- 1.2 Explain how the ball games played by natives of North America and Mesoamerica reflected the worldviews of their participants.

- 1.3 Outline the components of European “festive culture” and the role they played in European societies.

- 1.4 Describe the aspects of European and African cultures that migrants attempted to reproduce in the Americas, along with the functions they served.

- 1.5 Summarize the characteristics of New England’s “lawful sport,” and explain how and why “lawful sport” differed from other forms of sport practiced in the Americas in the colonial era.

- 1.6 Articulate the ways that religious and political ideas impeded the development of sport in the early years of the American Republic.

In September of 1889, at a spot high in the Appalachian Mountains, two groups of Cherokee Indians squared off against each other in a ball game. At the appointed time, young men representing the rival communities of Wolf Town and Big Cove lined up face-to-face, wielding elaborately carved ball sticks and wearing eagle feathers tightly bound into their hair. Hundreds of spectators ringed the ball ground, which ran beside a river and was marked at either end with a pair of upright poles that served as goals. To one side lay closely guarded piles of the goods that players and spectators had wagered on their teams. As the players eyed each other, an elder urged them to play with honor, and to keep their composure when faced with injuries or setbacks. Then he tossed out the ball, and the players exploded into action.

“Instantly twenty pairs of ball sticks clatter together in the air, as their owners spring to catch the ball in its descent,” anthropologist James Mooney wrote in an appropriately breathless account of the contest.

In the scramble it usually happens that the ball falls to the ground, when it is picked up by one more active than the rest. Frequently, however, a man will succeed in catching it between his ball sticks as it falls, and, disengaging himself from the rest, starts to run with it to the goal; but before he has gone a dozen yards they are upon him, and the whole crowd goes down together, rolling and tumbling over each other in the dust, straining and tugging for possession of the ball, until one of the players manages to extricate himself from the struggling heap and starts off with the ball. At once the others spring to their feet and, throwing away their ball sticks, run to intercept him or to prevent his capture, their black hair streaming out behind and their naked bodies glistening in the sun as they run. The scene is constantly changing. Now the players are all together at the lower end of the field, when suddenly, with a powerful throw, a player sends the ball high over the heads of the spectators and into the bushes beyond. Before there is time to realize it, here they come with a grand sweep and a burst of short, sharp Cherokee exclamations, charging right into the crowd, knocking men and women to right and left and stumbling over dogs and babies in their frantic efforts to get at the ball.1

The centuries-old Native American ball game, which the Cherokee called “anetso” and French missionaries gave the name “la crosse,” touched on many aspects of Cherokee culture. The strength, speed, agility, and daring that the participants displayed were the same qualities required in hunting and warfare. The excitement of competition, as well as the elaborate ceremonies that preceded the games, drew communities together. The game was also intimately intertwined with Cherokee religion. Cherokee legends told of games played by animals and gods. Players prepared for a match both physically and spiritually, with the help of a conjurer who guided them through time-honored rituals and called on powerful spirits to assist them in the game. As a result, the games became far more than exciting distractions from everyday affairs; they also served as powerful affirmations of community, identity, and worldview.

Outside Cherokee lands, in the burgeoning cities that increasingly marked the North American landscape, a very different kind of game held sway. Like anetso, “base ball” was played with balls and sticks. It too was an exciting game that displayed strength, speed, and daring and drew communities together. But it was only a few decades old. Its rules had been shaped not by centuries of play, but by an official committee charged with standardizing the game. Most of the fans who flocked to the newly built ballparks had migrated to the city from the countryside, or immigrated from abroad, and they often had little to connect them besides their support for the local team. Perhaps most significant, at its top levels baseball had become a commercial enterprise, much like the countless other business endeavors that were rapidly turning the United States into one of the world’s most industrialized nations. The ballparks to which urban dwellers so eagerly flocked had been built in anticipation of profits from ticket sales. The newspapers that published enthusiastic accounts of the games sought to draw readers and increase circulation. The players, most of whom had roots in Europe or Africa as well as North America, were professionals, tied to their teams not by kinship or community, but by salaries and contracts.

The new game spoke to the changes that had transformed the North American continent since the arrival of European explorers set off a massive, worldwide migration that left few corners of the globe untouched. Starting in the 1500s, a flood of Europeans and Africans—the latter generally brought against their will—overwhelmed the native populations of North and South America as well as the islands that ringed the Caribbean Sea. Propelled by the imperatives of commerce and Christianity, the new arrivals established colonial societies across the continents. In the temperate southern regions, colonialism was fueled by the profits from large-scale agriculture—sugarcane in the Caribbean and South America; cattle ranching in South America and Mexico; and cotton, rice, and tobacco in the southernmost colonies of North America. Further north, colonists established family farms and a small-scale manufacturing sector that would eventually help spark the Industrial Revolution.

As the inhabitants of these new worlds built new societies, they also shaped new sports, drawing on the circumstances in which they found themselves as well as on their rich range of sporting traditions. Considering the sporting traditions on which inhabitants of the future United States drew, as well as the processes by which they shaped their games, helps illustrate some of the many ways that sports can be linked to culture as well as the broad range of cultures that contributed to the sports we know today.

The North American Ball Game

While natives of eastern North America enjoyed many different kinds of games and competitions, none held as much significance as the ball game. The game, played from Huron and Iroquois territory in the north to Creek and Choctaw lands in the south, varied from community to community, depending on tradition and circumstances. Players might wield one stick or two, teams might have fewer than a dozen members or more than a hundred, ball fields could vary from 300 yards to half a mile in length. But no matter what the rules, young men—and sometimes young women—grew up carving sticks, tossing balls, and dreaming of someday representing their communities. Stories of the game were woven throughout Native American legends: telling, for example, of the day a powerful spirit presented the Fox people with a stick and a buckskin ball and taught them how to play, or of the time that kindness to a bat and a flying squirrel helped the creatures of the air win a game from the creatures of the earth.

Ball games often took place at times of spiritual significance, such as the end of harvest, and were frequently held to honor or solicit the deities who had taught humans how to play. They were accompanied by elaborate rituals. Among the Cherokee, for example, preparations for a game began weeks in advance. Players linked themselves with speed, flight, and keen vision by weaving bat wings through their sticks and gathering eagle feathers to tie into their hair. Community members began to gather goods for wagers and plan the ceremonies that would precede the event. These preparations reached a peak the night before the game, when each town took part in an all-night dance, and the players embarked on a 24-hour fast. With fires burning, musicians playing, and babies sleeping in the bushes, men, women, and children danced and chanted. During the dance, and again the next morning, each team made several ceremonial journeys to a nearby river, where the conjurers performed their final rituals.

Most ball games were played between individual communities, which often nurtured longtime rivalries. But because of their close connections with natural and spiritual forces, games were also linked to larger events. Games could be used to formally mend relationships or settle disputes among feuding communities. Like ritual dances, they could also be employed in efforts to influence the weather, or help heal the sick. In the fall of 1636, for example, Huron communities living around Lake Huron were ravaged by influenza, one of the many deadly diseases that Europeans brought to the New World. French Jesuit missionaries reported that one renowned Huron conjurer “had declared that the whole country was sick; and he had prescribed a remedy, namely, a game of crosse, for its recovery. This order had been published throughout all the villages, the Captains had set about having it executed, and the young people had not spared their arms.”2

The Mesoamerican Ball Game

Further to the south, in areas that would become known as Mexico and South America, traditional games and entertainments included yet another kind of ball play. In a tradition thousands of years old, athletes of the Aztec, Mayan, and other Mesoamerican empires competed on specially built courts, striving to send a heavy rubber ball through a stone ring. As with other traditional games, rules varied from community to community, but players were generally forbidden to use their hands, feet, or head, and instead propelled the ball with their hips, thighs, and shoulders. The largest and wealthiest empires had created elaborate, urbanized societies, and these cultures gave rise to highly skilled corps of specialized athletes, who performed for royalty and other elites. These players could compete for hours without allowing the ball to touch the ground. The game required tremendous strength and ability, and idealized images of strong, young ballplayers appeared throughout Mesoamerican art, indicating the high regard in which these athletes were held.3

The Mesoamerican game was also closely tied to Mesoamerican religion. Ball games frequently appeared in legends: most notably in Mayan accounts of a pair of gods known as the Hero Twins. According to the legend, the Twins descended into the underworld, rescued the Lord of Corn by defeating the Lord of Death in a ball game, and then ascended to the sky. Mesoamerican religious beliefs cast the world as an ongoing struggle between the opposites of day and night, good and evil, and life and death—a contest neatly encapsulated by competition between two groups of ballplayers. This link between the games and the balance of cosmic forces could make the stakes for ball games especially high. Mesoamerican beliefs held that human sacrifices played a key role in keeping the gods happy and the cosmos in balance. As a result, players who lost a game might also lose their lives.

European Sporting Traditions

The Europeans who arrived in the Americas carried their own sporting traditions. European Christianity drew sharp distinctions between material and spiritual worlds, and European sports bore little religious significance. Many traditional games and entertainments had in fact emerged from the continent’s pre-Christian era and were often frowned upon by Christian authorities. But sports and games played important roles in European societies, and many colonial-era migrants sought to reproduce European traditions in their new settings.

One function sports served in Europe was to distinguish the upper from the lower classes. Sports that required costly investments in land or animals became ways for elites to cement bonds among themselves and display their superior wealth and abilities to commoners, who were frequently prohibited from engaging in such exalted activities. In England, the limited forest land belonged to the landed gentry, and hunting stags or foxes was a favorite sport of kings and noblemen (common Englishmen rarely had the chance to hunt, and those who journeyed to the colonies generally had to learn hunting skills from Native Americans). Horse racing, another elite pursuit, took place at specially built tracks attended exclusively by wealthy patrons. In Spain, where many families earned their wealth from cattle raising, the well-to-do were also avid hunters, and public festivities frequently centered on the display of upper-class horsemanship (the Spanish word for “gentleman,” caballero, translates literally as “horseman”). As part of these events, which often took place in a town’s public square, elaborately garbed noblemen engaged in cattle-roping exhibitions, in mounted mock combat, and in bullfights—the original bullfighters were noblemen who fought on horseback.4

European commoners, on the other hand, pursued their sporting activities as part of what historian Richard Holt has termed a “festive culture” that prevailed across Europe during the medieval era.5 This culture underscored the social bonds that organized communal life, and offered participants a brief means of escape from the hard work that dominated their daily activities. European villagers invariably concluded their harvest season with a festival of thanks accompanied by hearty eating, drinking, dancing, and game playing. In addition, the Christian calendar offered numerous opportunities for communities to stop work in order to honor patron saints, celebrate major events in the life of Christ, and commemorate numerous other saints and martyrs. Some of these...