This is a test

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

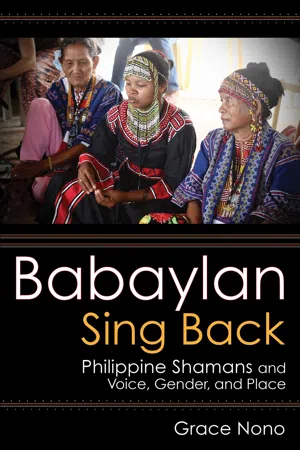

Babaylan Sing Back depicts the embodied voices of Native Philippine ritual specialists popularly known as babaylan. These ritual specialists are widely believed to have perished during colonial times, or to survive on the margins in the present-day. They are either persecuted as witches and purveyors of superstition, or valorized as symbols of gender equality and anticolonial resistance.

Drawing on fieldwork in the Philippines and in the Philippine diaspora, Grace Nono's deep engagement with the song and speech of a number of living ritual specialists demonstrates Native historical agency in the 500th year anniversary of the contact between the people of the Philippine Islands and the European colonizers.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Babaylan Sing Back by Grace Nono in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

WHO SINGS?

A Baylan’s Embodied Voice and Its Relations

It is 1989. I am in the mountains at the boundary of Agusan del Sur, Davao del Norte, and Bukidnon. Fresh out of college, where I read books about the babaylan’s demise, I am having an unexpected encounter with a living Native ritual specialist referred to by the Manobo as baylan. Keeping my bewilderment to myself, I come face to face with Laco, a tall, slender man with deep voice and dark eyes, his countenance more recessed than that of the convivial datu (chief) who warmly welcomes the group of literacy teachers I am traveling with.1 An hour or so later, my companions and I head downhill to the next village where we will spend the evening. I, who, until then, have heard only Western and westernized songs from school, church, radio, and television, listen for the first time to an oral chant by a mother named Baunsoy whose lilting voice moves me deeply.

Traveling back to the lowlands I feel inspired but also confused and angry. Why have voices like Laco’s and Baunsoy’s been hidden from my generation and perhaps from generations past? What conspiracy is it that has been suppressing such voices from rising to our ears? I will spend the next decades finding ways to further listen to the voices of ritual specialists, many of whom are oral singers.

Sixteen years and several ritual specialist encounters later, I find myself at the edge of the back seat of a motorcycle, hugging my seventy-eight-year-old mother in front of me as we move along an old winding logging road toward the innermost parts of our home province, Agusan del Sur.2 We try to keep our balance as the driver swerves or obstinately moves forward in response to the challenges posed by the slippery ditches and mud pools. Awaiting us at our destination is an event that many Filipinos like ourselves do not believe happens in the modern age: a panumanan (ritual) officiated by a baylan (Agusan-Manobo ritual specialist). Practices like these are widely thought to have perished during the Spanish and American colonial periods, a notion welcomed by those who see Indigenous pre-Christian and pre-Islamic practices—labeled paganism by the orthodoxies that have tried to eradicate or convert Native populations—as, at best, deficient and, at worst, a road to hell. Such a view is equally embraced by agents of the modern nation who have relegated such practices to the past or to the realm of ignorance and superstition. In contrast to these detractors are those who lament the alleged disappearance of these traditions, particularly the predominantly women priests who led them, who have become idealized as protofeminists and/or as land-based symbols of anticolonial resistance. Both camps generally agree that the woman my mother and I are about to meet either no longer exists or exists without a voice to make a difference.

My mother struggles to remain stable on the seat in front of me. I keep stopping her aged body from tilting as the fragile vehicle bumps and sways. Raised during the middle years of the American colonial period, when Indigenous ways were actively suppressed following campaigns by the Spanish, she, too, grew up unaware of the baylan. It is only a year after this trip when she finds out that there have been mamuhatbuhat ritual specialists among her aunts and uncles in Camiguin, and seven years after her death when the Kamiguin tribe itself, is declared ingidenous.

At sundown, we arrive in barangay Panagangan in the town of La Paz and are warmly welcomed by the baylan’s brother in-law, Jose, and his wife Florencia. Both Jose and Florencia are Agusan-Manobo pastors of the local Free Methodist Church, and my mother’s former students. We have come at their invitation after my inquiry if I may be allowed to listen to a baylan’s voice in ritual to know how ritual participants listen to and understand this voice. Although opposed to baylan practice, pastors Jose and Florencia lend their secular expertise as Agusan-Manobo language experts to my study. I am to rely on them for the transcriptions and translations to kuntoon (modern) Manobo, Visayan (one of Mindanao’s lingua francas), and English of the old Manobo utterances of the baylan and the abyan (the baylan’s spirit companion, helper). Pastor Jose himself was once a baylan before he became a pastor so it was not too long ago when he, himself, sang what was believed to be the voice of his abyan. Also welcoming us upon our arrival is the baylan’s niece, young woman Robilyn.

My mother and I meet the baylan. Her name is Lordina “Undin” Potenciano. Quietly observant, she seems to be both with us and not with us; present, yet in a world beside ours. Her composure—like those of other ritual specialists I have met—is not projected or displayed. Unlike the outwardly heroic depictions of the babaylan in books, films, television, and the Internet, here is a ritual specialist who gives concentrated care to arranging beads for ritual rather than to arranging blatant political resistance. Undin introduces herself to us through a tod-om (song).3

Mgo uda paliman kad udaPadongog kad man mayonsadPigdangkagan ko hipag digDawdangolan aw dodogi kayAman aboy ka nu tiLimuk pinintu tiajun ni mgoUda aw nolinugoyAw natinayod on nighibayandugTugaman ta no mangoyag no songlitanMakayogoy on no timpo din aw inggadPad ilingon no mga uda inggadPad ilingon nu igpanawsangkuabAd kakuli insondad ad kapuy-ajat anoy adManiajun anoy on man manim-Bang to tugaman ku no pintuInggad pad itingon nu igduyagidAd kakuli insondad ad kapuyajatTo kona kay no iyan on aw konaNo iyan on narambaja to GinuoNog pamintod to kadigoy to ingodnonTo domyog to yugnabanon noTahomon ku nalinugoyA da man najon-od su inggadPad ilingon nu inawa inawaKay ogkamiling to inajun kuNo potong no iyanandaMan iyan iyananda manOgtabang to dajawag ku noPotong no iyanda man iyanIyan nanda man ogtabang toDajawag ku no potong iyan nandaMan miglimbutung to kahungan ku noPintu kagona ku no linimukNo aboy ka nud dinaan koWada ogkayawangan di wadaKalinugoy nasimuyag nasimuyagOn pagtini-ajunay noy no inggadPad ilingon nu ko kani mig-timamanwa on to kanoy no kahunganMigtumbilaan ku inanoy on nasim-buyag koy on nigbaliwaan on buyanNigbayluhan on payagkajun noAdu ka nu dinaan inawagTo buyan to kanig panimbanagSilat si panagkajun igkapana-Wodsawod ku si dadaya kugOyogon si yuha kug anugunonTo kagona ku no pintu aw dangatOn to kaway no ogtumbilanganSu matuod man iyan awKalinimuk nanda kahungan taKo pintu nan da to kagona taNo kinuyang kid ogmakagtey pang-Idap buyawan sayapiNogkatapnoy na adu ka nu dinaand-adka nud mgo iyanKo iyan kow on mogpasibu iyanKow on mupuangod to kagonaKu no pintu nakayogob kadTukib kad takokos on no limukKabos on no pa-iyak adu kaNu dinaan aboy ka nudMonsanga aw dodogi kay noBukyad bangkulis ka ko iyanKad mayonsag dig dangkagan no hipagNo dawdongulan no makatapnoyTo kanay no tumbilangan aduKa nud dinaan aboy kaNud mon sanga sambajonTo Magbabaja adu ka nudMonsonga su inggad pad ilingonNu igduyagid ad kakuli igsondadAd to kapuyajat konad noAguwantahonon to kanay no kagonaKanay nogtumbilangan su hintawoPad tog pangidap hintawo padTogpa makuli manNaan to wada ti-ajun taTo wadad on timbang ta no wadadMag pangidap wadad mag ogmakanga-aMaginona nanda mag tumbilangA to tuyugan no nalindog bayoyNo natangkajang iyan onMagbayagadan ku ko kani kayKani kay abyan ku kani iyanOn man ogpaigu iyan da magAjangatan ku man.

Hear now, my friend.

Now listen carefully.My brother-in-law [Jose] requested for me, and reallyI am requested a lot.So you,Lady [Grace], we havenot seeneach other before.It is a veryrare time, evenas I amnow suffering from too manydifficulties and brought to much hardship.No matter howhard I have tried to workas a womanI still have a very difficulttime. I am destined for difficulties.If not forthe Creator who controlsmy life, who directs human beings,who guides humanity,I thought I woulddie. And evenif you say that “this is your way”this is really the way my lifeis. My onlyhelp is my friend,the spirit.My ultimatehelperis my spirit friend. S/he is theonly one who protects me, sucha woman like meand reallythere is no other way except tobe separated frommy husband. Evenif you saw meat home, in our lifeat home, we ha...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Who Sings?

- 2. Shifting Voices and Malleable Bodies

- 3. Song Travels

- Afterword

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index