![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Dramatis Personae: Twelve Architect-Leaders

FROM ENGLAND TO NEW ENGLAND, the theories and values of the Arts and Crafts movement crossed the Atlantic, resonating with the men and women who contributed to an emerging Arts and Crafts sensibility in Boston. In England the movement was inspired by the views of John Ruskin and William Morris, and from an early date, their writings were published and read in the Massachusetts capital. At the turn of the twentieth century, when English architects were designing buildings that reflected Arts and Crafts themes, Boston architects stayed current with the work of their overseas colleagues and were receptive to English trends—trends that became the basis for the Arts and Crafts architecture in New England.

The Arts and Crafts movements in England and Boston took shape in different ways. In England the movement was promulgated by the formation of guilds, leading to the show sponsored by the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1888. The movement in Boston, on the other hand, began with the exhibition held in the spring of 1897.1 Perhaps the people in Boston first organized an exhibition rather than a guild because they understood that an exhibition would involve a finite time commitment. Then, too, the fact that the Boston exhibition was organized by a craftsman printer, Henry Lewis Johnson, and not an architect may have been relevant. Johnson was motivated by a desire to showcase the finest work then being produced by his fellow artisans. Yet as in England, architects in Boston were involved from the start, and ultimately they would promote the cause through a variety of activities. In 1897, when the prospectus for an exhibition of the Arts and Crafts was circulated, thirty-seven Bostonians signed on as endorsers. Among them were nine architects: Robert D. Andrews, Clarence H. Blackall, Francis W. Chandler, Charles A. Cummings, Bertram G. Goodhue, Alexander W. Longfellow Jr., R. Clipston Sturgis, C. Howard Walker, and H. Langford Warren.2

Johnson was an effective organizer, and much of the success of what became the nation’s first major Arts and Crafts exhibition must be attributed to him. At the same time, he was able to achieve what he did because of the widespread interest in the Arts and Crafts ideas that had taken hold in Boston by the late 1890s. Charles Eliot Norton, who taught fine arts courses at Harvard, had created an awareness of Arts and Crafts concerns and sympathy for the movement’s goals; and to a lesser extent, the architect Henry Hobson Richardson, who ran his practice in the Boston suburb of Brookline, contributed through his admiration of Morris and other English craftsmen. Also important were Boston’s institutions and organizations that brought the design community together: Harvard, MIT, the Museum of Fine Arts and its school, the Boston Society of Architects, and the Boston Architectural Club. In March of 1897, shortly before the exhibition opened, Candace Wheeler, president of the Associated Artists of New York, commented that an attempt had been made for several years to organize such an event in New York City. But she believed that Boston had “the best nucleus for industrial art work” because of its many schools.3

Advocacy for the craftsman was regularly expressed at the meetings of the Boston Society of Architects. At an 1893 meeting, Andrews presented a paper in which he spoke about the need to reunite architecture with artistic crafts.4 Two years later, he went further by declaring to his colleagues that the craftsman was a more vital man in art than the architect. Greek and Gothic buildings, he argued, were mainly the work of craftsmen, unlike the less admirable Roman and Renaissance buildings in which the architect was the “dominating power.”5 One may wonder how Andrews’s colleagues reacted when he told them that “the decline of art in any period was contemporaneous with the appearance of the architect.” This remarkable view did not seem to provoke any objections—at least any that were recorded. Whatever the case, Andrews’s desire to bring together the craftsman and architect was widely shared.

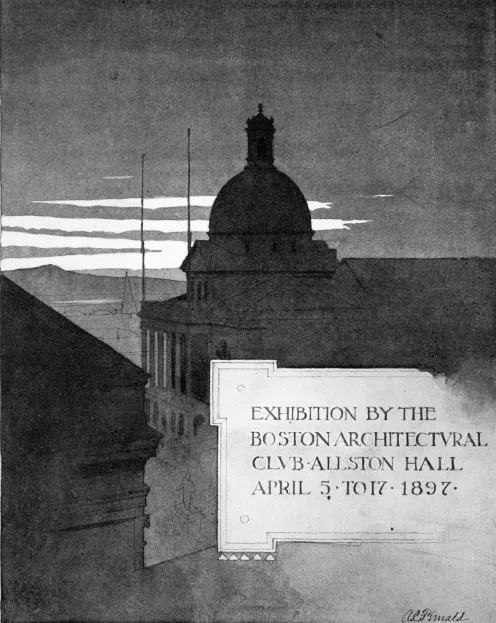

As for the logistical demands of organizing the Arts and Crafts exhibition, the architects provided Johnson with a successful model. Beginning in 1890, architectural exhibitions had been presented by the Boston Architectural Club, sometimes sponsored jointly with the Boston Society of Architects.6 When the Arts and Crafts exhibition opened to the public on April 5, 1897, the accompanying exhibition on architecture was organized by the club. Andrews chaired the exhibition committee and was assisted by a team that included architects George Edward Barton of Boston and Walter Cope of Philadelphia. On the catalogue cover was a wash drawing of the restored Massachusetts State House (fig. 1.1), designed by Charles Bulfinch and dating from 1795 to 1798, a recent preservation victory achieved mainly through the efforts of the architectural community.7

FIG. 1.1 Cover of Boston Architectural Club exhibition catalogue, wash drawing by A. C. Fernald, 1897.

Before the Arts and Crafts exhibition came to a close, a group of men and women met to consider whether to hold another exhibition and form a sponsoring organization.8 By June 1897, the Society of Arts and Crafts was chartered. The architects among the founders were Andrews, Barton, Longfellow, George Russell Shaw, Walker, and Warren. Founding craftsmen included Johnson, along with carvers Hugh Cairns, John Evans, and Johannes Kirchmayer, and the printer Daniel Berkeley Updike. Academic supporters included Charles Eliot Norton and Denman Ross, and patrons included Arthur Astor Carey and Samuel D. Warren II (not closely related to the architect, if related at all).9

Once the society was established, a governance structure was adopted. Members voted for individuals to serve on a council, and then the council elected its officers and made the decisions for the organization. Three tiers of membership were created: Apprentices, whose designation was soon changed to Craftsmen; Masters, who were distinguished designers; and Patrons, who were supporters and paid higher dues. Most of the architect members were promptly advanced from the level of Craftsman to Master, whereas most of the craftsmen never became Masters. By 1900 the society had opened a salesroom to display and sell its artisans’ work. In order to evaluate the entries and maintain a high standard, a jury was appointed. Among its thirteen members were the architects Longfellow, Shaw, Sturgis, Walker, and Warren. Ross also held a seat.10 The jury readily offered criticism and rejected work, which frustrated the craftsmen but enhanced the reputation of the organization. Within a few years, the society had attracted some of the nation’s most prominent craftsmen as members, including Henry Chapman Mercer from Doylestown, Pennsylvania; Adelaide Alsop Robineau from Syracuse, New York; and Artus and Anne Van Briggle from Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Nevertheless, most of the members who joined the Society of Arts and Crafts came from New England, and the organization reflected the region’s culture in many respects. To begin with, the way in which many of its leaders maintained close connections with England became a recognized characteristic of the society. Its mission, dedicated to promoting “mutually helpful relations” between architects and craftsmen, was written by Norton and directly derived from his friendship with Ruskin and Morris. Through the early twentieth century, the goal of bringing together architects and craftsmen continued to be supported by England’s Arts and Crafts leaders, and the Boston organization excelled in this effort as well. Indeed, in 1910 the English architect C. R. Ashbee wrote a letter on behalf of a countryman visiting Boston, asking the society’s salesroom manager to show the guest projects in which “the craftsmen actually work for and with the architects.”11

As the Society of Arts and Crafts flourished, it reflected the culture of Boston in other ways. For example, its leaders shared the desire to emphasize education. The society maintained a library, sponsored lectures, presented large and small exhibitions, and published the magazine Handicraft. Education to the society’s leaders meant the study of history, whether of architecture or the applied arts, following the lead of the region’s educational institutions. Less obvious, yet also a reflection of Boston’s character, was the orientation of the society’s leaders toward law and governance. To be sure, this interest became widespread in America during the Progressive Era. Yet a regard for the law permeated Boston’s professional and academic communities at the turn of the century. By this time, the members of the Boston Society of Architects revised their bylaws almost every year.12 In Cambridge, Harvard Law School was expanding and emerging as a nationally prominent institution. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. also generated interest in the law as he delivered public lectures and wrote about the workings of the courts and judges. Boston’s professionals mixed with each other. In fact, Holmes and his wife, as well as Boston attorney Louis D. Brandeis and his wife, visited the 1897 Arts and Crafts exhibition.13 When the leaders of the Society of Arts and Crafts established their jury in 1900, at least some of them would have been responding to the contemporary discourse on jurisprudence.

With the opening of the society’s salesroom that same year, the organization asserted its commitment to free enterprise. Carey, the second president of the society, hoped to advance the socialistic goals of Morris, but the society’s other leaders would not subscribe to this direction, and Carey resigned late in 1903. That November, Warren, in his role as the group’s third president, explained to the members, “The fact of William Morris’s socialism and the socialism of his friends has led both the friends of the arts and crafts movement and those who are indifferent to it to lay too much stress on socialism as connected with artistic production.”14 In the following year, the society moved its salesroom from 14 Somerset Street to 9 Park Street, and by 1905, it had become self-supporting. In Boston, the Arts and Crafts movement was tempered by an Emersonian emphasis on the individual. For the architects who served in leadership positions, the society was not a charity. It had to succeed, and it did succeed by developing a market for beautifully crafted products.

From 1897 through 1917, forty architects joined the Society of Arts and Crafts.15 Twelve of them moved into leadership roles, serving as officers and members of the governing council, members of committees, and members of the jury.16 All twelve became Masters, another indicator of their prominence in the organization. As practicing architects, they demonstrated their commitment to “mutually helpful relations,” collaborating with the artisan members of the society by embellishing their buildings with the craftsmen’s sculpture, carved wood, tile, and stained glass. Their buildings also were conservative, notable for their restraint. Several of the twelve architect-leaders had lived and trained in England. Several were educators and historians. In terms of their personalities, all twelve were self-confident and energetic. Short biographies of these twelve individuals document the roles they played in governing the Society of Arts and Crafts and highlight some of the more important buildings that they designed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

FIG. 1.2 Robert Day Andrews.

ROBERT DAY ANDREWS (1857–1928), a charter member of the Society of Arts and Crafts, served on its council and sat on the Workshops and Classes Committee (fig. 1.2).17 A graduate of Hartford High School in Connecticut, Andrews entered the office of Peabody and Stearns in 1874.18 During the 1875–76 academic year, he was a special student at MIT, and he then worked with other architects and traveled through Europe. When he returned to Boston in the early 1880s, he was hired by Richardson.19 Cheerful and entertaining, Bob Andrews was described as “always a brainy man.”20 From 1884 to 1890, he worked in partnership with the architect Herbert Jaques; they were then joined by A. Neal Rantoul, the firm becoming Andrews, Jaques, and Rantoul.

Andrews’s leadership in restoring Bulfinch’s Massachusetts State House (1896–98) was much admired, and this success led to his restoration, with H. Hilliard Smith, of the Bulfinch State House in Hartford, Connecticut (1918–20). Assisted by Sturgis and William Chapman, Andrews oversaw the design and construction of the wings added to the Massachusetts State House (1914–17). He designed a number of...