I.Law – Justice and Art as Interface

‘The call for justice’ is a phrase that has a nice feel to it, or an almost inescapable positive connotation. Yet historically and practically speaking, almost all calls for justice have been experienced by many as annoying, at first. The reasons are simple. Calls for justice imply the change of an existing order, they imply accusations, they demand the uncovering of what had been disguised, they seek that people and other legal subjects or persons, are held accountable – they will not let bygones be bygones. In a sense, these calls connote a principle, stubborn, relentless ‘no’. The annoyance concerns all parties, moreover, from those who do not want to be bothered with things that happened in the past to those seeking justice by returning to that past. It may even be the case that people who seek justice feel annoyed with themselves. Yet, their ultimate goal is to find a confirmation that things can be put in order, be restored, that the pain that has been inflicted and the damage that has been done may at least be acknowledged, perhaps compensated, or sufficiently repaired. Eventually, those who seek justice seek a ‘yes’.

Should the call for justice be answered, this answer will have to come from a system of law. In this context, it is unfortunate that the terms of justice and law are often used interchangeably if not confused. Still, in origin, they are distinct. Justice, in this study, concerns what people consider or feel to be just or unjust.2 Law concerns the vast array of officially acknowledged competences, rights, obligations and prohibitions that people are supposed to live by. The relation between the two has preoccupied many, from ordinary citizens to prominent philosophers and legal scholars. Some, especially in the last century, have argued that there is no intrinsic relation. The law is a practical instrument that keeps an existing order intact, whilst the issue of whether laws are just is purely a matter of subjective assessments and interests. To them, law is an ordo ordinans: an order that keeps something else in order. Its justness is only a legal concern in so far as laws are based on the proper ground and applied justly.3 Many more have argued that any legal system that claims to safeguard justice should answer to standards of fairness, equity and justness formulated both from within and outside of the system of law. Here, the question is how law should answer to principles of morals or ethics.4 Instead of separating the two or trying to frame one in terms of the other, this study considers the relation between law and justice as the meeting of two spheres. It is a meeting that takes place time and again, in our case, through the interface of art.

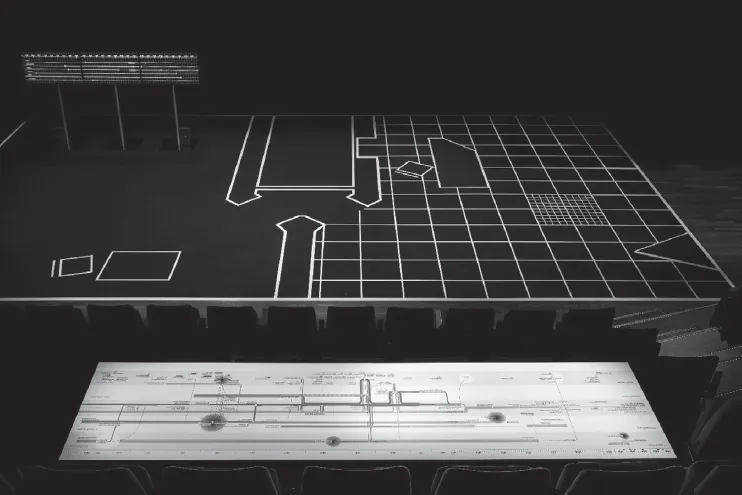

Art is an umbrella term here. In the interdisciplinary field in which this study inscribes itself, Law and Literature is the commonly known combination. Yet the field has expanded considerably in the last decades in addressing much more than just literary works. In our case we will consider a performance (chapter two), a couple of theatre plays (chapter three), a few novels (chapters four, six and seven), an essay (chapter four) and two poems, but also an etching and maps (chapter five), contemporary works of art that concern themselves with turning suburban grass turf into ‘edible estates’ (chapter six) and a movie (chapter eight). A couple of times the work of the independent London-based research group Forensic Architecture will be of relevance. The group gathers architects, artists, coders and scholars of all sorts, including legal ones, to work together against powers that want to obscure a truth. To this order, the group moves both inside and outside of the art world and when operating inside it, they make a form of art that perhaps readers would not immediately recognise as such. For instance, one case they investigated was the murder of Halit Yozgat in Kassel, Germany, in 2006.5 On the basis of its research, the group made a video entitled 77sqm 9:26min.6 The video was exhibited differently in several exhibitions, such as the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London, or at BAK, Utrecht, in October 2018. In both cases, the digital model representing the ground plan of the space in which the murder took place, and that is presented in the video, was projected on the floor, on a 1:1 scale.7 The photograph below gives an impression of what this looked like at BAK:

Figure 1.1 Forensic Architecture, 77sqm_9:26min (2017)

Installation with three-channel video, 25:54 min, reenactment video, 15:14 min, carpet with floor plan, and diagram, installation view Forensic Justice at BAK, ‘basis voor actuele kunst’, Utrecht, 2018–19, photograph: Tom Janssen

Perhaps one of the first questions a reader might have is: How should I read this? Well, one should read it, in part, as a report on the investigation into Halit Yozgat’s murder. In the next chapter we will explore in more depth why the reflection on art’s mediality is of relevance. Truth does not simply show itself, in either a system of law or in a realm of justice. The question of how truth is shown by specific media is thus of relevance. The media used by Forensic Architecture, here, invite the viewer not to enjoy a smart solution, but to start searching together, if only to check things, and to do so performatively. We see the floor plan of the internet café owned by Yozgat. This is not something to only be looked at; anyone can walk in it. It is an icon of the ability to check things or connect to them, and this checking and connecting relies on the audience’s ability to follow the process of research. This process is represented here in the foreground on the white tableau. It is purposefully placed in the space of the audience, as one can see from the shadows of the chairs. The tableau places the investigation into the wider context of the NSU Complex (on which more in chapter three). It may be clear that this is another kind of art than, for instance, the often mentioned fourteenth-century fresco in the Palazzo Publico in the fair city of Siena, entitled Good and Bad Government, by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. In the case of Forensic Architecture, research was involved, for instance into the acoustics of the space, in an attempt to find out whether someone could or could not have heard gun shots. The case itself was connected to a much larger investigation into an underground political-criminal network called NSU, and its possible connections to secret services. All in all, this is not so much a form of art that is to be enjoyed or judged or only interpreted; rather, this is a form of art that instigates public participation. As a consequence, to many, works like this are admirable, while to many others they are annoying.

As this example shows, the meeting of the spheres of law and justice – in their connoting different kinds of power and following different kinds of logics – is either provoked or made palpable, sensible, imaginable and hopefully productive through art. Again, most of these qualifications, just like ‘a call for justice’, have a nice feel to them. Still, the very meeting itself is often, or even mostly, also annoying. Forensic Architecture’s work may annoy because it is also art. And the now canonical nineteenth-century English author George Eliot was annoying in her own times (as were most of the realist painters people now highly valued, by the way). One of the reasons that art can be annoying in its connecting law and justice is that any call for justice is always, in a sense, out of date: it ought to have already been answered. Or, the call for justice addresses bygones that should have already been corrected. Through art’s interface unresolved issues of justice are made into something of the present and the future. That is, they are made to persist. It is this persistence that connotes justice’s claim towards universality, despite its subjective origins. Yet although the appeal to universality is needed because most unresolved injustices cannot be solved by the parties directly concerned, art’s interface is not intrinsically a universal one. Rather, art offers a meeting space, filled with frictions, of alternative possibilities.

Both the annoying force implied by art’s interface of alternative possibilities and justice’s appeal to universality can be traced when a disturbing case goes unresolved. One such a paradigmatic case is the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 on 17 July 2014, in the eastern part of Ukraine. As far as current evidence suggests, high-ranking Russian military officers and Ukrainian separatists were the culprits of this crime. The loss of lives, most of them Dutch, had traumatic effects on those involved both directly and indirectly. It had traumatic effects for a nation.8 Up until now, the only work of art operative with regard to this case (and by implication the only interface) is a memorial site that was opened in July 2017. This memorial site consists of 298 trees planted in the shape of a crossed ribbon, one tree for each of the victims. The ribbon is surrounded by sunflowers that act as an index to the fields blossoming during the month of July in the Ukraine. At the heart of these two rings there is an amphitheatre with the names of the victims.9 The obvious aim of this site is to keep those who have passed away alive, in and through memory. Yet, the site is also a work of art that embodies a call for justice, in the double sense this term connotes in English: law and justice.

As for the call to law, in 2017 the countries gathered in the Joint Investigation Team (The Netherlands, Belgium, Australia, Malaysia and Ukraine) decided that the case was to be dealt with by a Dutch court, according to Dutch law. In one sense, then, the memorial site from 2017 called forth the legal handling of the case that started on 9 March 2020.10 Still, even if the culprits ever appear in court, the issue remains whether law is able to do full justice, when law is considered as that which satisfies a general sense of justice. First of all, in the realm of justice there are many parties involved with different interests; it is as much a realm of consensus as of dissensus.11 This is where the appeal to universality quickly reveals its limitations. The question is, moreover, whether demands for justice can ever be answered fully by means of law. In relation to this, the memorial is much more than simply a matter of collective memory or an appeal to law. It is also a site that embodies the impossibility of ever closing this case. It embodies an ongoing call for justice that exceeds the limits of law.

The MH17 case also illustrates how the meeting of the spheres of law and justice is related to two distinct forms of power. By studying the confrontation between the two forms of power at stake in the cases that follow, I will use a distinction made by the Jewish-Dutch philosopher Benedict de Spinoza: potestas and potentia.12 Power, or potestas, connotes the organisation of societies by means of the rule of power, or the rule of law. Potentia refers to the empowering abilities of beings and things to exist and realise themselves on the basis of their desires, including their desires for justice.13 The two relate to one another first of all in terms of their inverse directionality: potestas exerts itself in a top-down manner, and potentia acts from the bottom up. Furthermore, there is a difference in scale. The space of the potential will be more forceful, in the end, than the domain of sheer power. The space of the potential is always excessive; it exceeds anything. Analogously, when Hannah Arendt posited natality at the heart of politics, as something that all human beings embody, this connoted the potential of a new beginning. Consequently, as political philosopher Charles Barbour noted, for Arendt ‘action is never localised in a single sphere or realm, but enigmatically conditions and threatens every such a realm’.14 Action is political action, then, that can threaten an existing order, and as such illu...