![]()

1

“A CHANGE IS GONNA COME”

1964 AND THE BATTLE LINES OF TODAY

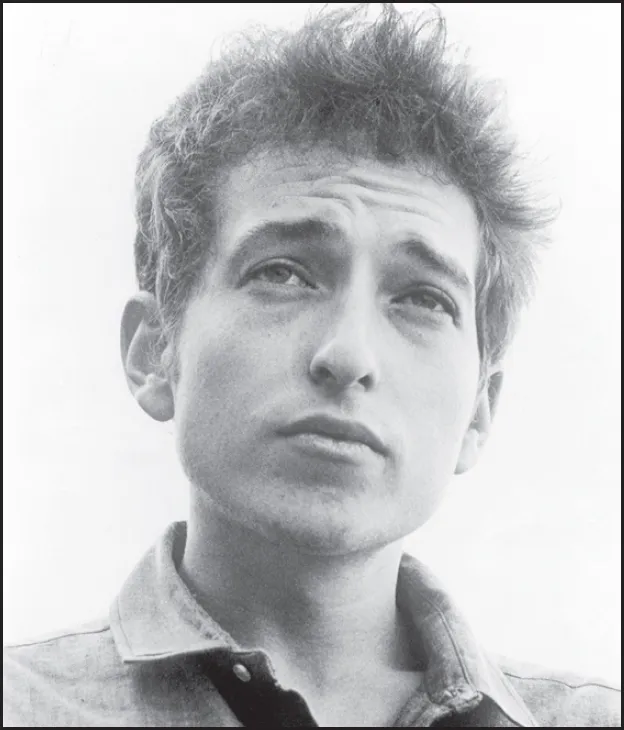

Bob Dylan

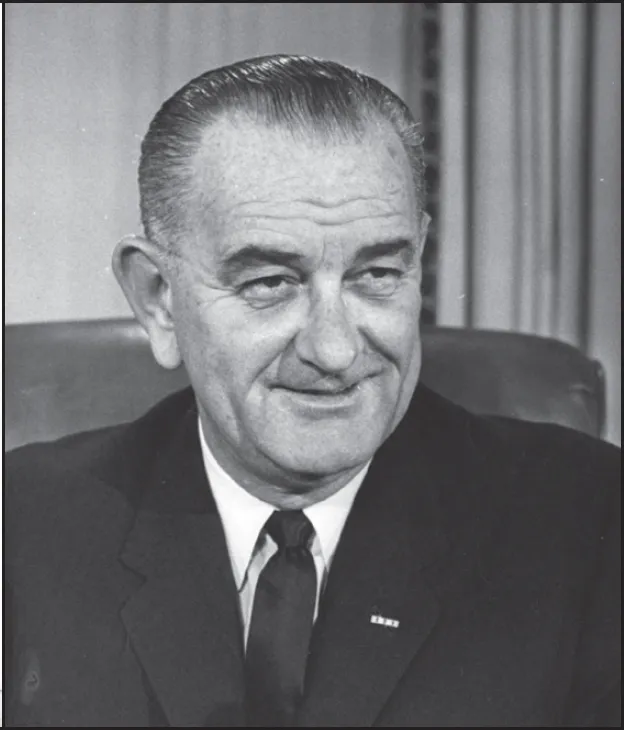

Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

The chance won’t come again . . .

For the loser now will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’.

—Bob Dylan, “The Times They

Are a-Changin’1

![]()

SAM COOKE’S HOPEFUL MESSAGE in his 1964 song “A Change Is Gonna Come”—that change had been far too slow, but he knew it would come—was timely.2 Change, massive change, was about to come at a stunning pace. It was in that year that what we think of as “the sixties” arrived. “The differences between 1963 and 1969 were dramatic,” as Kurt Andersen notes in his 2020 book, Evil Geniuses: “The clothes, the hair, the sound, the language, the feelings—and the changes happened insanely fast.”3

In the chapters that follow, I argue that 1964 was the key year in the shaping of modern America. It launched the most intense, meaningful, and—on balance—positive period of change in American history. Moreover, the changes that occurred then still define the political, social, cultural, and economic battle lines along which Americans contend today. The “culture wars” that have been so prominent in the divisions of the nation since the 1980s center largely on the remarkable transformations that began in 1964. To appreciate what is at stake in the political and cultural conflicts of the 2020s, it is essential to understand the pivotal year explored in this book.

But history is not mathematics. Decades in culture, politics, and attitudes often don’t match calendar numbers. What comes to mind when we hear “the sixties” went from the closing days of 1963 well into the early 1970s. Similarly, a year in history doesn’t necessarily equate to 365 or 366 calendar days. Nineteen sixty-four, or what I call in this book the “Long 1964,” began in late 1963 with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the arrival in America, albeit not yet in person, of the Beatles in November and December 1963. It continued through the summer and early fall of 1965, with Lyndon B. Johnson’s major escalation of the American war in Vietnam, the release of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” and “Like a Rolling Stone,” the Voting Rights Act, the Watts uprising, and key portions of Johnson’s Great Society legislation. When I refer to 1964 in what follows, it should be understood as shorthand for that extended period.

Here’s a useful way to look at how that time relates to now:

Nineteen sixty-four was a time of righting wrongs. Today, one of the two major political parties is fully dedicated to wronging rights—reversing the progress initiated in the period I explore here. The once Grand Old Party has defined itself as both anti- and ante-1964.

One of the prominent battle lines in the politically inspired culture wars emerged in 2019 when the New York Times introduced “The 1619 Project,” which identified the introduction of slavery into the English colonies in North America four centuries ago as one of the defining moments shaping American history. Opponents swiftly countered with arguments supporting the traditional view that Enlightenment ideals underlying the Declaration of Independence in 1776 are central to the meaning of America, and the question became a culture-war litmus test.4 In fact, 1619/1776 is not an either/or choice. Americans have always been, in a variety of ways, in historian Michael Kammen’s accurate designation, a “people of paradox.”5 Surely, the greatest of all American paradoxes is that, from the start, the new land of freedom was also a land of enslavement. Much of American history can be seen as a tension between these two facts. Those who have attacked the 1619 Project have conveniently ignored that, in her introduction to it, Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote, “the year 1619 is as important to the American story as 1776. [emphasis added]”6 That assertion should not be controversial.

The paradox that is the United States took bodily form in Thomas Jefferson. He enunciated the radical vision, with its majestic ideals of freedom and equality, but failed miserably to live up to those ideals. Yet the promise of America has rightly inspired even those people who have been excluded from it. African American poet Langston Hughes may have said it best in 1936: “America never was America to me / And yet I swear this oath— / America will be!”7

It was in the Long 1964 that the full promise of 1776 was for the first time opened to those for whom the legacy of 1619 had for so long defined America. Through the Twenty-fourth Amendment outlawing the poll tax, the Civil Rights Act banning racial discrimination, and the Voting Rights Act opening the vote to all, the United States for the first time became a full democracy.8 As of this writing in 2021, the Republican Party is engaged in an all-out assault on that democracy. While the radical right seeks to make political capital out of insisting that 1776 is what America is all about, they are plainly on the side of returning the nation to its 1619 inheritance as was in place prior to 1964.

Zeitgeist:

A Dylan-Johnson Duet

History is punctuated by discontinuities that alter its trajectory. The key to the occurrence of such watershed moments is less the leaders than a sociopolitical environment that is receptive to change. Though Lyndon Johnson’s vision and ability to get things done in Congress were clearly important in the change that occurred in 1964, more essential was that Johnson found himself, to use an evolutionary metaphor, in an environmental niche for which progressive approaches were adaptive. That is apparent in the dramatic cultural change that took place during the same period.

On January 13, 1964, Columbia Records released Bob Dylan’s third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’. It seems to have gone unnoticed, both then and since, but the messages in Johnson’s State of the Union speech in which he declared war on poverty and Dylan’s song that provided the album’s title in the first two weeks of 1964 were, while drastically different in tone and approach, parallel in the thrust of what they were saying about the times.

When Dylan sang about the chance not coming again and the loser later becoming the winner because the times were a-changin’,9 he could have been channeling the new president. These words almost exactly reflect how Lyndon Johnson saw the situation and the opportunity he had to change America for the better. Dylan and Johnson—the poet and the president—almost seemed to be singing a duet. This synchronicity was, of course, entirely unplanned. Dylan had written the song in September and October 1963, while JFK was still alive, and he was reflecting the sense of hope that Kennedy had provided but not fulfilled and, even more, the bold actions of civil rights workers.

The sort of convergence that happened with Dylan and Johnson is usually referred to as mere coincidence. Coincidence it certainly was, but was it mere? When two things coincide chronologically, it may be meaningless, or it may reflect something meaningful about that time. When Dylan’s friend Tony Glover picked up a typed copy of the song’s lyrics in Dylan’s apartment in September 1963 and read aloud the line, “Come senators, congressmen, please heed the call,” he asked, “What’s this shit, man?” Dylan shrugged his shoulders and responded, “Well, you know, it seems to be what the people like to hear.”10 Precisely. Such a coincidence of a musician’s words with the arguments of an activist president suggests that something was “in the air.” And one of the things in the air—or “blowin’ in the wind”—in 1964 was a desire to improve the conditions of society’s “losers.”

This interpretation is important when considering Bob Dylan’s work. While he was deemed the voice of protest, the spokesman for his generation who, as Zora Neale Hurston said of her protagonist in her 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, put the “right words tuh our thoughts,”11 Dylan has long denied that he had any such intention. Always fiercely refusing to be pigeonholed and frequently reinventing himself, he reacted against the embrace in which the civil rights and antiwar movements tried to hold him.12 “The left tried to lionize him,” Pete Seeger wrote in a letter to his father in 1967; “he reacted violently against this, saying fuck you to them all.”13 Dylan’s answer to the claims that he was the leading voice of protest may have been contained in a song on his next album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, which was released seven months later, in August 1964: “It Ain’t Me Babe.”14

It is difficult to believe that Dylan was not authentic when he wrote the powerful words of protest and social justice contained in so many of his songs in 1963 and ’64. But if we look at the songs and their reception as reflections of the spirit of the time, Dylan’s purposes and sincerity don’t matter. He was a major voice of his generation, even if he didn’t want that role. And, speaking of sincerity, the same is the case with LBJ’s words at this time. He wanted to uplift the downtrodden, but regardless of his candor or lack thereof, the enthusiasm with which many Americans greeted his calls for fundamental change indicates that, like Dylan, Johnson was voicing sentiments that were “in the air” and “what people want[ed] to hear” in 1964. This odd couple calling for changing times in January 1964 would have had a hard time singing in harmony, but growing numbers of those who formed their audiences were eager to harmonize with them. If the duet of Bob Dylan and Lyndon Johnson were to be given a name, the most appropriate one would be Zeitgeist.

One part of Lyndon Johnson might have wanted to sing along with the sentiments in another song on Dylan’s January album, the powerfully antiwar ballad “With God on Our Side.”15 To do so, though, would have required LBJ to overcome his manhood insecurities, and, as I’ll discuss later in the book, that wasn’t in the cards. It was over the issues addressed in “With God on Our Side” and the question of the Vietnam War that the duo of Dylan and Johnson split apart. The majority coalition of Americans that came together in 1964 in support of the ideal of “for the loser now will be later to win” would be torn apart over the war. One result would be that the big winner in 1964, Johnson, would be “later to lose.”16 Another consequence would be a shortened life span for the spirit of the times of 1964.

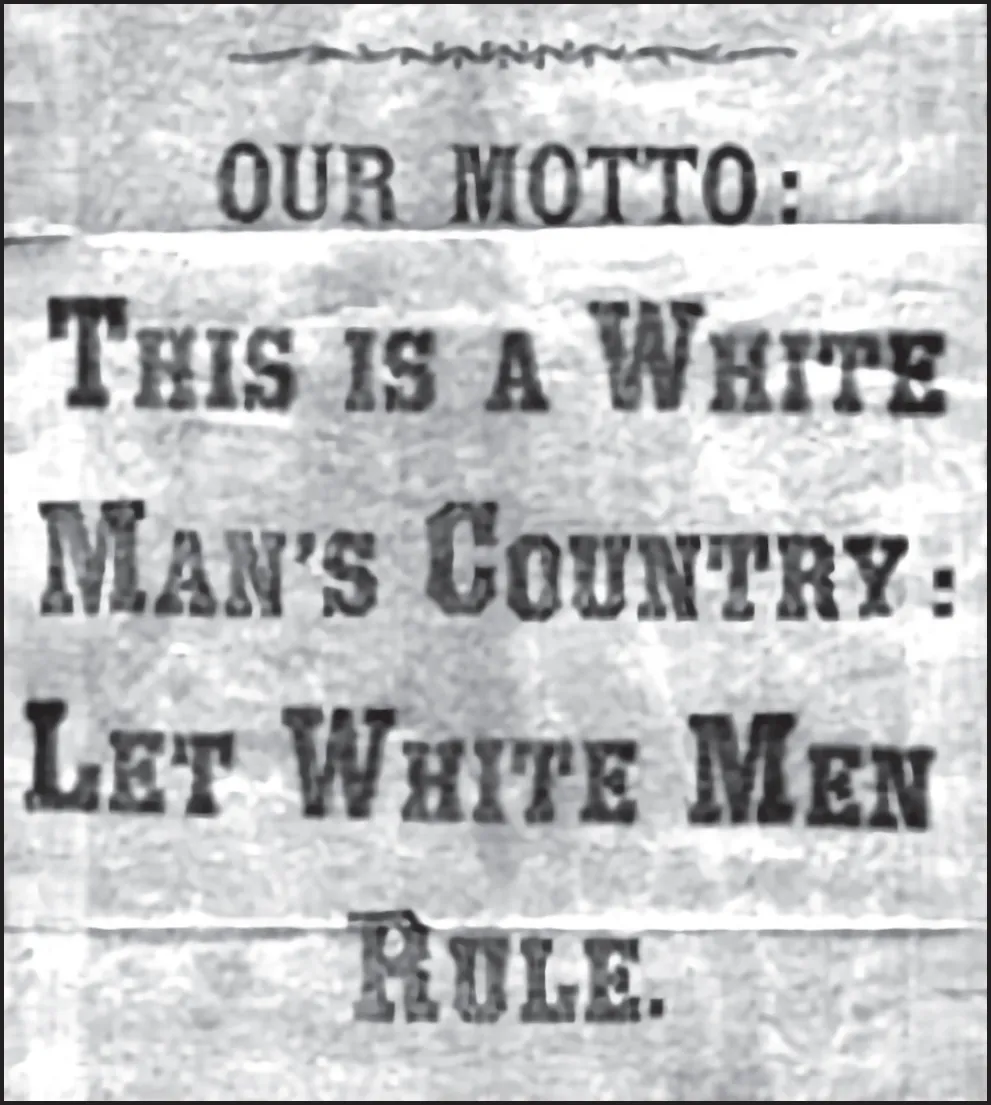

The motto of the 1868 Democratic presidential ticket on the above poster directly raised the basic issue of American history: The question of whether America can and will be a free, diverse, inclusive democracy or “a white man’s country” has been with what became the United States since 1607, when English settlers arrived in a land already occupied by people who had skin of a color different from theirs.

It was central at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, in the virulent sectional disputes of the 1850s and the enslavers’ rebellion, during Reconstruction and the “restoration” of white rule in the South, through the Jim Crow era, and in the civil rights and women’s movements, and it is fundamental to the bitter confrontation today between progressives who advocate for the continued advance toward the ideals of America and those who are regressive—the sort of people Russian writer and artist Svetlana Boym categorizes as “restorative nostalgics.”17 They seek, British journalist Nick Bryant says in When America Stopped Being Great, “refuge in a misremembered past.”18 They want, as Anne Applebaum puts it in Twilight of Democracy, “the car...