![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Are Bacteria Sentient?

At first I thought cells were just rudimentary pieces, like bricks; now I realize each cell is a universe. Without cells there would be nothing.

KONCHOK

Bacteria of all sorts, some appearing as big as grapes, dance and spin on the pale cinderblock walls of the Dharamsala classroom. The monks and nuns stop and point and exclaim. Something has changed; the room shifts.

We forget about the afternoon heat pressing down on us and stare excitedly at the bacteria projected in real time from the microscope slide onto the wall before us.

Was this what it was like for the original microbe hunters—Leeuwenhoek, Spallanzani, Hooke, and their ilk—when they first uncovered this astonishing world centuries ago? Imagine the thrill and the fear of discovering that so many zillions of creatures existed everywhere, all around us, all the time. It must have been almost beyond belief.

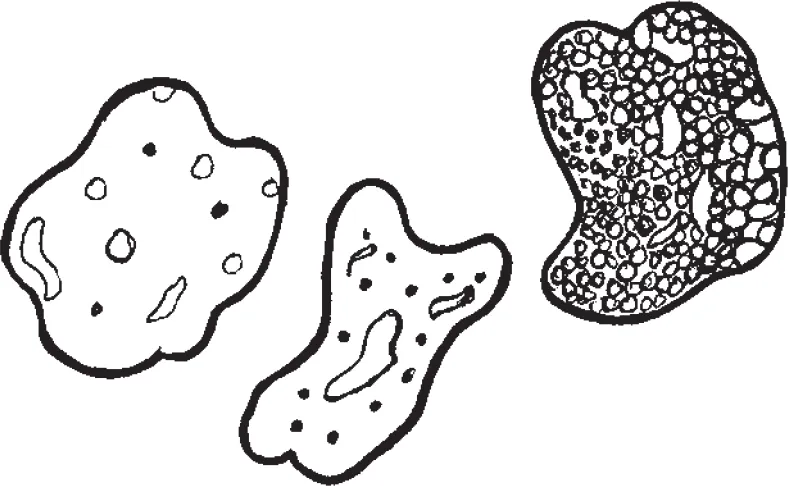

These particular Dharamsala bacteria, these single-celled “beasties” as Leeuwenhoek called them, were grown by the monks and nuns in the class (some of the drawings of the bacteria Konchok made that day are in figure 1.1). They swabbed the beasties from doorknobs or fingernails and nurtured them on bacterial food plates whipped up from cornstarch we found in the campus kitchen.

One of those microbe hunters, Robert Hooke, coined the word “cell” in 1665; when he saw those tiny walled spaces in the tissue of cork that he was the first to ever see, they reminded him of the cells monks live in.

FIGURE 1.1 Konchok’s sketches of the first bacteria he ever saw, projected from the microscope onto the classroom wall in Dharamsala.

In our group discussing whether bacteria are sentient beings, we had two opinions; we were split. Before the experiment, I myself was thinking, “Bacteria are not sentient.”

But when we saw the images and the bacteria moving toward food on the wall, then I thought this was real. I thought they could be sentient. Before this, I thought just because they move and find food, this doesn’t mean they have to be sentient. But in the microscope, it looked like the cells had a purpose. After our experiments, we monks talked a lot. I thought: Maybe these bacteria have senses, maybe even emotions. They “feel” where food is. Maybe they are sentient.

This was the first lab experiment we ever did; we saw the bacteria on the wall.

Most of us got it then—what scientists do. In actually doing it, not just saying it, many monks changed their minds.

Back in my monastery, the monks always ask, “How do you do experiments? How do you use the equipment?” In our own philosophy, we debate on what Buddha taught, we explore the logic of texts and rationality.

When you say scientists hypothesize, experiment, analyze, monks say “how?”

When we did this experiment, things made sense. This became strong evidence. We had some negative ideas taught to us about science, but that experiment clarified some doubts about science.

Some monks didn’t believe in science. But when we did this experiment, we saw this with our own eyes, a kind of truth. Not only that, the evidence really inspired us a lot. That experiment motivated us to learn more science and explore more.

Our goal is to create a lens, literally and metaphorically, through which information is experienced in a rich context. The monks and nuns learn about cells and the cell theory—that cells are the fundamental unit of all life—and they learn this in the larger context of the themes of biology and of how scientists ask questions and approach problems.

Why should Tibetan monastics care about cells? How is it related to their lives and experience? This is where the question of bacterial sentience comes in; it engages a core Buddhist concept. Buddhism teaches that sentient beings are aware creatures, such as humans and other animals. Compassion should be shown to all sentient beings, and any such being can be reincarnated as any other. So, if bacteria are indeed sentient beings: (a) any person might be reincarnated as one, (b) any bacterium might be reincarnated as a human, and (c) we should show compassion to all bacteria. At first, many of us Western scientists might dismiss out of hand as trivial, silly, or irrelevant, the question of whether bacteria are sentient. But as we’ll see, such an attitude is, and was historically, perhaps to our ultimate detriment.

The monks and nuns, then, have a vested interest in exploring the question of whether bacteria are indeed sentient. And we have established a culturally relevant lens through which to teach cell biology. In order to answer the sentience question, other questions, at the heart of cell biology, must be addressed: What are cells and of what are they made? How do cells sense, translate, and respond?

We wrestle and walk with these questions six hours a day for eight days with discussion and laboratory experimentation. Science is about experiments. The bacteria sentience question is the monks and nuns’ door into experiments.

BACTERIA ARE a powerful model system. A model system is an organism studied in order to ask fundamental biological questions. All living things are made of cells, and the basic constituents of cells have been conserved throughout evolution. Questions relevant to more complex organisms like humans can often be addressed in relatively simple organisms such as bacteria, flies, or yeast. These creatures also are cheaper to work with, are easier to maintain, have short life cycles, and garner fewer ethical concerns than “higher” organisms more similar to and engaged with humans, such as chimpanzees or dogs.

Experiments on animals such as mammals also, of course, occur in the West. And the question of which model systems to use, or whether to use any at all, resonates especially with Buddhists, who show compassion to all sentient beings.

FIGURE 1.2 A typical human cell on the left and a typical bacterial cell on the right.

The monks and nuns are not comfortable conducting experiments with anything living—unless it is plants, which they do not consider sentient, or something like bacteria, the sentience of which is the question under investigation. The monastics would not kill any organisms, but do, in our Dharamsala classes, study organisms that are already dead.

So our choice of bacteria as a model system to explore in Dharamsala is effective, because studying bacteria demonstrates the power of experimentation and the importance of model systems without introducing, at least initially, the problem of studying sentient beings.

Those bacterial cells dancing on the wall (and at first seemingly so different from our own cells) are in many ways very similar to human cells. Figure 1.2 shows a typical human cell on the left and a typical bacterial cell on the right (not drawn to scale). And because they are ubiquitous, easy to access, and grow quickly, and their maintenance and study is cheap, bacteria are excellent for asking fundamental questions about cells—even with limited supplies in a makeshift lab in the foothills of the Himalayas.

During my study of Western science, I realized that it promoted my knowledge and wisdom, and developed my insight. Simultaneously, it has given me the desire to learn more and made me more inquisitive in whatever activities I do.

In fact, desire and grasping, craving, wanting more is usually considered something undesirable, something to be given up in Buddhism. But knowledge is an exception to that rule; learning new things is an activity that one should engage in all one’s life.

In some circumstances the Buddhist concepts of nonvirtue, ethics, and sin restrained me somewhat in accepting some of the scientific explanations and methods. For instance, in Buddhism you do not kill sentient beings or make them suffer; and as a monk, I took a vow to remain celibate and not to kill, steal, or lie. But in the laboratory, science students are required to design and perform experiments using animal-based model systems. Dissecting these formerly living beings and interacting with them is one of the most effective methods of achieving many scientific goals, that is, examining firsthand their anatomy and learning much about the causes of birth and death. I have found it personally difficult to perform dissections and manipulation using real animal models. Essentially, all animals are our kin, possible past or future versions of our own reincarnation, so making them suffer makes us suffer.

When I took introductory biology at Emory, we used zebra fish in experiments in the laboratory. It was interesting to observe and play with the different stages of zebra fish development, but Buddhists believe that dissecting and using an animal or insect for experiments is nonvirtuous and unethical.

The Buddha encouraged his disciples to have respect for all life forms and not to unnecessarily damage or destroy any living thing.

“Should scientists use animals in research?”

The Dalai Lama answers in what I have come to learn is his classic style. He echoes Buddha’s teachings: respect all sentient beings, and do not intentionally harm or destroy them. But, the Dalai Lama also says, we must examine each case carefully and balance the issues at play. What if experiments on ten mice could potentially save the lives of thousands of humans?

This question about animal research comes from a student at a teaching of the Dalai Lama’s I am attending at a Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamsala. These villages in India adopt and raise Tibetan children who escaped, often without their parents, from their home country and help transition them into society. Thousands of such children escaped in the latter half of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, but the route became more dangerous and often fatal as a result of more active Chinese military intervention after the unrest in Tibet in 2008. One of the young Tibetan students asks the question.

I am struggling to follow the translation of the question and the Dalai Lama’s answer through earphones plugged into a transistor radio, like the kind I used to sneak into my junior high classes to listen to college basketball tournament games in the 1970s.

I try to focus on the Dalai Lama’s response, but my legs went numb an hour previously. I was shown through a side door by the Dalai Lama’s sister to sit on the stage where he would talk. This sounded good, until I saw I would be sitting on a floor mat cross-legged for the next three hours—a less-than-exciting prospect for an inflexible six-and-a-half-foot-tall American.

We had wound our way up to the village in a tiny car on one of Dharamsala’s unimaginably narrow roads on which cows, buses, trucks, innumerable motorcycles, and pedestrians—locals and truth seekers of every stripe—perform their daily death-defying waltzes (as I move forward toward you, you simultaneously move toward me into the space I just vacated, and vice versa). If you mess up, it’s a very long way down the mountain. Also, don’t forget, just to add more spice to the adventure, you have to keep track of the fact that Indians drive on the left-hand side of the road.

When the Dalai Lama escaped from Tibet over the Himalayas in 1959, the prime minister of India at the time, Jawaharlal Nehru, offered him—and all the other exiled Tibetans in the years since—different communities and resources to maintain their culture. Dharamsala, where we initiated our project teaching science to monastics, became the home for the Tibetan government in exile. Other lands in southern India, where we now teach in three large monastic universities, were established as refugee communities.

WE CHALLENGE the monks and nuns in our class to explore how they might “ask” the bacterial cells themselves to address the sentience question.

The monastics struggle first with a definition for “sentience.” Does it mean merely “the capacity to sense,” or does it imply some higher level of awareness? Tibetan Buddhism holds that plants are not sentient. Are bacteria different from plants? Might science have one definition for “sentience” and Buddhism another?

We settle on a set of experiments that will at minimum address the question of whether bacteria can sense. The monks will grow bacteria and, while observing them under the microscope, will add different chemicals, one per experiment, to one side of the microscope slide to see if the bacteria show any clear change in movement away from or toward the chemical. They will use chemicals that are predicted to attract, such as sugar, as well as some predicted to repel, such as acid.

We make the bacteria-food plates, and the monks and nuns swab different surfaces to pick up bacteria and then transfer them to the plates. In Dharamsala’s very warm summer temperatures, the bacteria grow quickly, and soon our makeshift laboratory smells like a neglected locker room.

Western science says each species lives in a certain kind of environment—fit for itself. An ant fits his environment. He needs food; in order to get food, he has to run out, to search for it.

In Buddhism we say all sentient beings are like our parents or brothers. The question of killing in science is different; it’s more of an ethical than a religious problem.

Buddhists say that an ant is a life, a sentient being. It is not good to take life. It’s very negative. In Buddhism, an ant from many thousands of years ago could have been our relation.

In terms of evolution, you could say all animals are brothers, as ants use many of the same genes and proteins that we have to do similar things. But we also believe animals have the same senses and emotions that we do—fear, hope. All sentient bein...