![]()

1 A New England Forest History

The trees that dominate New England’s landscape grow slowly in relation to the span of our own lives, and we see them as permanent and unchanging, a cherished natural constant in times when change is rapid and all too apparent. But a forest is anything but static, and the forests of New England tell two important, intertwining stories of change: one story of the forests’ natural processes, and another of their response to being alternately used and disregarded by people throughout history. This chapter describes the interplay between ecological forces and human activities that have shaped the New England forest, an understanding of which is essential for anyone approaching the complexities of forest management.

It is a mistake to believe that leaving the forest alone will ensure that it will stay as it is. The forest changes visibly and dramatically during strong winds, ice storms, outbreaks of disease and insects, and forest fires. Even between such sudden events, and even without human disturbance, the forest is dynamic because the woods change slowly but incessantly through succession. Succession is the constant process by which plants take over an area, change conditions of soil moisture, of fertility, and especially of light, then wane as they are replaced by other plant species that find the new conditions more favorable. (Forest succession is the term applied to this process as it occurs among tree species.) In addition to the changes in soil fertility and environmental conditions effected by the vegetation on a site, other factors such as climate, soil type, weather trends, and levels of seed production determine which plants will follow others in succession. Trees do not produce equal amounts of seed each year, and those that produce a good crop when weather conditions are favorable will have a better chance to take hold on a suitable site.

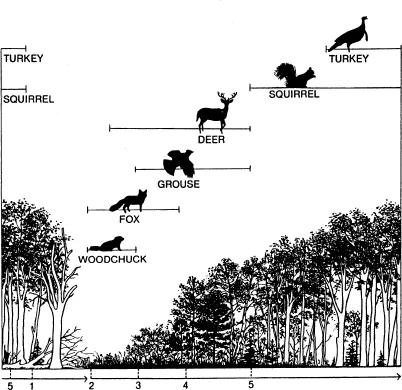

Fig. 1. A generalized pattern of forest succession in New England including animals typical of each successional stage. After a major disturbance in a forest (1), a site may be reclaimed by small plants (2). Then, over perhaps a century or more, the site might be occupied by a series of shrubs (3), sun-loving trees (4), and trees able to regenerate in shade (5). A disturbance could occur at any point in the progression, setting the vegetation back to some earlier stage of succession.

But the factors that direct succession, the interactions among them, and the precise ways in which they effect change in the forest have not all been identified, nor are they fully understood. Elements of chance (such as weather) are also part of the process, so succession is both complex and, to some extent, unpredictable. However, generalized and simplified patterns of succession can be described; an example is given in figure 1. Following a major disturbance, such as extensive windthrow (uprooting of trees by wind), fire, or land clearing, a moist upland area with fertile soil might first be claimed by grasses and brush, then by various sun-loving tree species such as aspen, gray and white birch, cherry, and pines. As their seedlings grow, these species eventually shade the once-cleared area, making it inhospitable for other seedlings of their own species. If the shade is not heavy, shrubs and trees with an ability to withstand some shade, such as oak, ash, and red maple, might form an understory, depending on available seed sources and soil conditions. An understory is a layer of small plants, shrubs, or small trees that establishes itself beneath the canopy of the tallest trees, which is the overstory. If little sunlight pierces the overstory, only small plants, and tree species able to survive in heavy shade, such as sugar maple, beech, spruce, and hemlock, can establish themselves on the forest floor. As the overstory eventually dies of old age or other causes, the understory will take advantage of the light, moisture, and nutrients previously claimed by the overstory, increase its growth rate, and succeed the old forest. Where there once may have been pine, aspen, cherry, or oak, there is now sugar maple, beech, spruce, or hemlock. If no major disturbance occurs, the forest will eventually be dominated by species that can regenerate in their own shade. Hypothetically, such species could succeed themselves for many generations; however, a disturbance in some form, such as a forest fire, wind, disease, or insect infestation, almost always occurs before this sequence can run its full course.

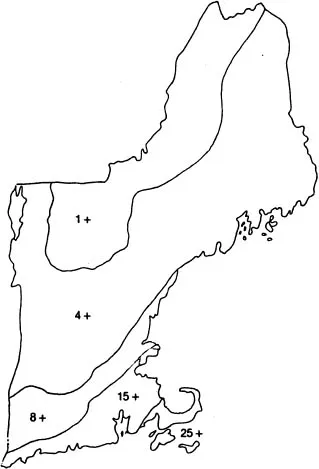

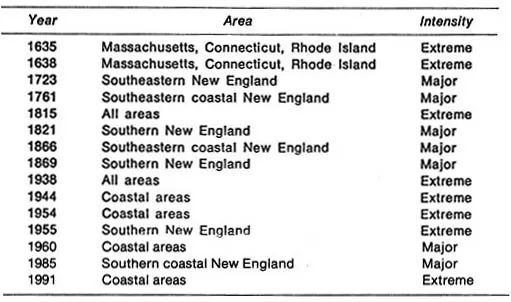

For instance, hurricanes have battered New England’s forests regularly. Figure 2 shows that severe storms have occurred frequently in much of the region. Table 1 lists the major hurricanes that have struck various parts of the region over a 320-year period.

It is important to remember that the succession pattern illustrated in figure 1 is a generalization of one path that succession might follow on a particular type of site. When the last glacier retreated from New England around ten thousand years ago, it left highly varied terrain and soils. Since plant and tree species are each adapted to particular soils, sites, and environmental conditions, the pattern of succession will vary from site to site.

Long before humans dwelt in New England, the dynamics of succession were operating; the typical succession was from small plants to shrubs, to sun-loving trees, to species able to survive in the understory. At some point a catastrophe would interrupt the process. During less violent disturbances small gaps were created in the overstory, and where sunlight was let in to the forest floor the understory was released or the less shade-tolerant species were invited to gain a foothold. During the most extreme disturbances large areas of the forest were burned up or blown down, returning the site to some early stage of succession: sun-loving trees, shrubs, or grasses.

Fig. 2. Numbers of hurricanes in New England from 1635 to 1991. (Adapted from E. P. Stevens, “Historical-Developmental Method of Determining Forest Transition” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1955).

All parts of a biological system are connected; as forest vegetation changes through the process of succession, other members of the forest community are affected. Because different vegetation provides food and cover for different animals, alterations in the plant and tree composition of the forest mean that wildlife habitat changes too. If a successional stage that includes a major source of food or shelter for an animal disappears or flourishes, that species’ population will tend to dwindle or increase, respectively (see fig. 1). For instance, deer depend largely on young forest and the shrubby edges of open areas for food; to the extent that such areas are unavailable, the deer population will be limited.

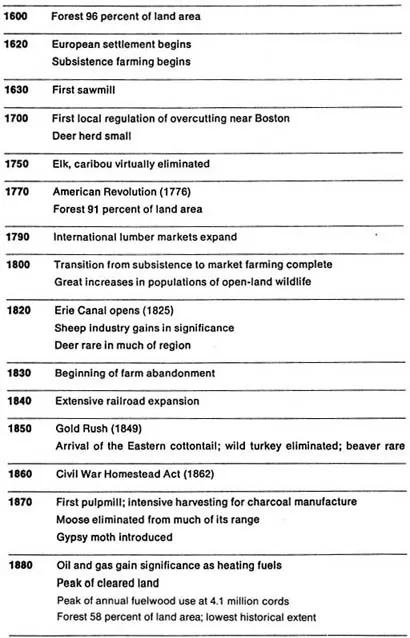

While change through natural disturbance and succession is one thread permeating the history of our forests, direct human influence is the second. The relatively brief history of land use in New England, summarized in figure 3, shows that the appearance, extent, and even the species composition of today’s forests have been affected by human use. Before the arrival of European settlers, woodland Indians cleared land near rivers and major inland lakes for food production. Because the Indian population was never large, most of the New England forest was unaffected by these practices. Except for wetlands, a few barren mountaintops, and major river valleys cleared by the Indians, the primeval forest dominated the region. Elk, caribou, mountain lion, and timber wolves populated this forest. Animals such as deer, grouse, hare, skunk, and quail were largely confined to the cleared land near Indian settlements and to early successional forests that had resulted from natural disturbances.

When European settlement of the region began in the mid-1600s wood was the household fuel. Near settlements, overcutting of the forests for fuel and lumber began early, and by 1700 some communities had enacted ordinances to regulate cutting.

Fuelwood harvesting has been significant and continuous from the time of colonial settlement until the present day, varying in this century with the price of oil. Another practice that has been maintained from the 1600s to the present is highgrading—taking only the best trees in a stand. This practice, followed for three centuries, has had a profound effect on the New England forest: each harvest of the biggest and best-formed trees further lowered the quality of the forest that remained. Even in remote areas of New England highgrading started early. The best trees—especially white pines—were cut, and floated down rivers to sawmills. England had already overcut its own forests, and the great timber wealth of New England proved to be strategically important. England was able to maintain naval superiority with the help of oak timbers and pine masts originating in the New England forests. The Broad Arrow Acts of 1691 and later ruled that all pines greater than twenty-five inches in diameter were the king’s property, to be reserved as masts for the Royal Navy. These laws were a major source of irritation to the colonists, who ignored the edicts and even set a few fires to deny the king his trees.

Table 1 Major Hurricanes in New England, 1635–1991

Sources: G. E. Dunn and B. I. Miller, Atlantic Hurricanes (Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press) © 1960 and 1964. Reprinted by permission; Harvard Forest, Petersham, MA.

Fig. 3. Summary of New England forest history from 1600 to present, by decade.

Elk and caribou, true wilderness animals, disappeared from New England as forest clearing began. Market hunting soon depleted wild turkey populations, and the beaver was rapidly extirpated from southern New England when its pelt became a medium of exchange in the colonies. As the beaver dwindled, so did the otter, mink, and muskrat for which beaver ponds are an important habitat element.

The heavy cutting of overstory trees allowed more sunlight to reach the ground, stimulating the growth of shrubs, herbaceous plants, sunloving trees, and sprouts from stumps. The result was a sudden change in wildlife habitat conditions. Species preferring the conditions offered by mature forests suffered, while animals like deer, which need brushy field-forest edges, flourished. In turn, the deer (and the settlers’ livestock) were food for the timber wolf, which multiplied far beyond its presettlement numbers and became the subject of intensive eradication attempts funded with large percentages of local taxes.

Following the American Revolution, land clearing in all but the remote and difficult areas accelerated as subsistence farms grew to commercial size to feed growing manufacturing centers to the south and east. The New England farmers toiled to remove the annual crop of stones from the land, depositing them in thousands of miles of walls that twentieth-century New Englanders cherish (frontispiece). In addition, increasing amounts of wood were needed as raw material for industry, and to provide charcoal for manufacturing processes such as iron smelting. Parts of the Massachusetts and Connecticut forest were cut repeatedly to supply charcoal and fuel from oak and chestnut sprouts that grew vigorously from stumps (fig. 49). This legacy of evenaged sprout hardwoods is still visible in today’s woods. Potash and pearl ash for fertilizer and glassmaking were produced by piling and burning unmerchantable timber during land clearing. When steam engines appeared, large sections of Vermont and New Hampshire forests were cut to fuel their boilers. At the end of the 1700s, international markets for New England lumber had been opened, adding to the drain on the forest. By 1840, much of the New England landscape was like a photographic negative of itself before settlement: not a thick forest punctuated by small openings, but a shorn landscape with scattered tufts of trees. Sixteen million acres of forest had been cut to run factories, make steam, charcoal, and potash, or simply to clear the land for farming and a growing sheep industry. In 1880, an estimated 42 percent of New England was open, with significant forest cover persisting only in the region’s high elevations and northern reaches.

Gone was the forested habitat of the wild turkey, which depended on large blocks of undisturbed hardwoods. The moose, portions of whose range in the spruce and fir forests had been decimated, was pushed from all but the northernmost reaches of the region. Although young forest and brushy forest edges are important food sources for deer, these animals also depend on some tall forest for cover, and especially on softwoods for winter shelter. Lacking cover and under heavy pressure from hunters, deer were pushed from many parts of New England by the mid-1800s. At the same time, the loss for woodland wildlife was a gain for animals of open land. Skunk and woodchuck populations exploded, and, by mid-century, the gray fox and cottontail rabbit had extended their natural ranges northward from the mid-Atlantic region into the now-open landscape of New England.

Continuing industrialization, the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the California gold rush in mid-century, the advent of the railroads, and offers of free western land to Civil War veterans began a long, steady agricultural decline and a period of large-scale land abandonment in most of New England. The higher wages and fancy life-style of the cities, tales of mining fortunes to be made, and the fertility of western farmland proved irresistible to those who had struggled with the rocky, thin soils on the hill farms of New England. The farmers went west; grains, meat, and wool came east on the railroads and through the Erie Canal to be sold at prices too low for competition from New England farms. Abandoned roads, cellar holes, lilac bushes, apple trees, and sometimes a potentially dangerous shallow well are all that remain of some of these farms. Deed descriptions often became vague and unclear when land changed hands during the remainder of the 1800s, and when many of the competent land surveyors followed the farmers west. Prospective buyers of woodland today are often presented with poor property descriptions which have been perpetuated since the time of farm abandonment.

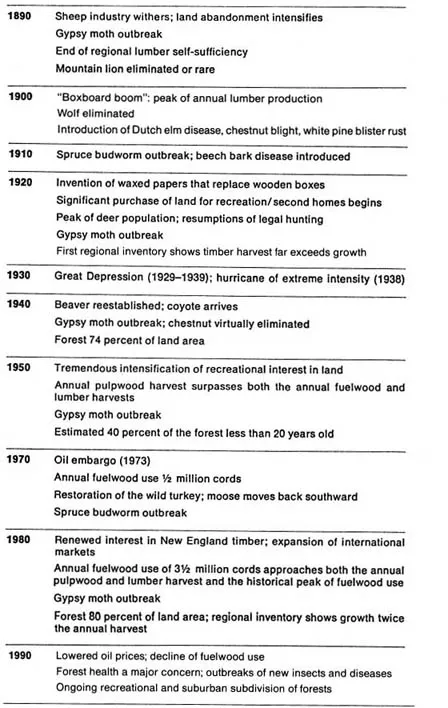

Fig. 4. White pine claiming an abandoned pasture.

Large-scale land abandonment restored the dominance of natural processes in the New England woods. Forests quickly took over the abandoned land, eventually regaining eight of the sixteen million acres cleared. Depending on the location within the region, seeds of pine, spruce, red cedar, or fir, which were able to penetrate the sod and take root in the soil beneath, established almost pure conifer stands in fields and pastures (fig. 4). The trees gradually formed a closed canopy, stifling the grasses and shrubs by cutting off their sunlight.

Much wildlife rebounded with the forest. The most notable comeback was that of the deer, although this was not always accomplished without the assistance of restocking. In 1878, seventeen deer were brought from New York State to Vermont to restore the species; today Vermont supports one of the highest deer densities in New Eng...