![]()

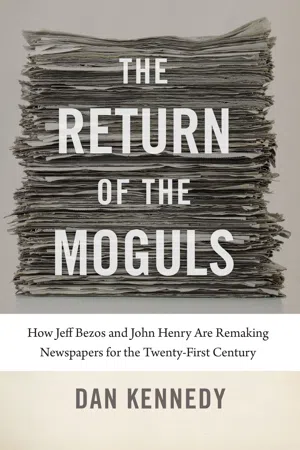

CHAPTER ONE

THE SWASHBUCKLER

Jeff Bezos Puts His Stamp on a Legendary Newspaper

THE NATION’S CAPITAL was still digging out from the two feet of snow that had fallen over the weekend.1 But inside the gleaming new headquarters of the Washington Post, a celebration was under way.

Among the speakers at the dedication festivities—held on Thursday, January 28, 2016—was Jason Rezaian, the Post reporter who had just been released by the Iranian government. “For much of the eighteen months I was in prison, my Iranian interrogators told me that the Washington Post did not exist. That no one knew of my plight. And that the United States government would not lift a finger for my release,” said Rezaian, pausing occasionally to keep his emotions in check. “Today I’m here in this room with the very people who proved the Iranians wrong in so many ways.”

Also speaking were publisher Frederick Ryan, executive editor Martin Baron, Secretary of State John Kerry, and the region’s top elected officials.2 But they were just the opening act. The main event was a short speech by the host of the party: Jeffrey Preston Bezos, founder and chief executive of the retail and technology behemoth Amazon, digital visionary, and, since October 1, 2013, owner of the Washington Post.3

It was Bezos who had purchased the storied newspaper from the heirs of Eugene Meyer and Katharine Graham for the bargain-basement price of $250 million. It was Bezos who had opened his checkbook so that the Post could reverse years of shrinkage in its reportorial ranks and journalistic ambitions. It was Bezos who had moved the Post from its hulking facility on 15th Street to its bright and shiny offices on K Street, overlooking Franklin Square.4 And it was Bezos who had flown Jason Rezaian and his family home from Germany on his private jet.5 Now it was time for Bezos—a largely unseen, unheard presence at the Post except among the paper’s top executives—to step to the podium.

Like Fred Ryan and Marty Baron, Bezos was wearing a lapel pin that announced #JasonIsFree, the Twitter hashtag that had, upon Rezaian’s release, replaced #FreeJason. “We couldn’t have a better guest of honor for our grand opening, Jason, because the fact that you’re our guest of honor means you’re here. So thank you,” Bezos began. Next he praised Secretary Kerry.

And then he turned his attention to the Post, combining boilerplate (“I am a huge fan of leaning into the future”), praise (“I’m incredibly proud of this team here at the Post”), and humility (“I’m still a newbie, and I’m learning”). For a speech that lasted just a little more than seven minutes, it was a bravura performance.

Bezos called himself “a fan of nostalgia,” but added, “It’s a little risky to let nostalgia transition into glamorizing the past. The past, the good old days, they take on a patina as time goes on. They become in our mind even better than they really were. And that can be paralyzing. It can lead to lack of action.” Next he invoked tradition, picking up on something Baron had said. “Important institutions like the Post have an essence, they have a heart, they have a core—what Marty called a soul,” Bezos said. “And if you wanted that to change, you’d be crazy. That’s part of what this place is, it’s part of what makes it so special. I’ve gotten a great sense of that in the last couple of years. I kind of somehow knew it a little bit from the outside even before I got here.”

And, finally, he offered some humor aimed at charging up the troops: “Even in the world of journalism, I think the Post is just a little more swashbuckling. There’s a little more swagger. There’s a tiny bit of badassness here at the Post.” Bezos paused while the audience laughed and applauded, then continued: “And that is pretty special. Without quality journalism, swashbuckling would just be dumb. Swashbuckling without professionalism leads to those epic-fail YouTube videos. It’s the quality journalism at the heart of everything. And then when you add that swagger and that swashbuckling, that’s making this place very, very special.”

The event closed with a digital ribbon-cutting that was even cheesier than it sounds, followed by a promotional video in which Marty Baron referred to the Post as “the new publication of record”—playing off a comment Bezos had made in November 2015 on CBS This Morning in which he said that “we’re working on becoming the new paper of record.”6 And it was over.

The vision Bezos outlined for his newspaper that day was simultaneously inspiring and entirely at odds with the wretched state of the news business. Of course, the Post is different—but in large measure because of Bezos’s vast personal wealth and his willingness to spend some of it on his newspaper. All was optimism and hope.

That said, people at the Post emphasized in conversations with me that Bezos was operating the paper as a business, not as an extravagant personal plaything. Although he had bolstered the newsroom, its staffing remained well below the level it had reached during the peak of the Graham era. But almost alone among owners of major newspapers, he had shown a willingness to invest now in the hope of reaching profitability in the future.

The Washington Post’s revival under Bezos is not just the story of one newspaper. Of far more significance is what it might tell us about prospects for the newspaper business as a whole. Thus everyone is watching Bezos closely to see whether he can apply the lessons he learned at Amazon to an entirely different—and arguably more difficult—challenge.

Bezos’s Post has invested an enormous amount of effort in building the paper’s digital audience. In 2014, Matthew Hindman, a professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University, identified a number of steps that newspapers should take to increase online traffic. Significantly, the Post has taken every one of them: it has boosted the speed of its website and of its various mobile apps; it has lavished attention on the design and layout of those digital platforms; it is developing personalized recommendation systems; it is publishing more content with frequent updates; it regularly tests different headlines and story treatments to see which attract more readers; it is fully engaged with social media; and it offers a considerable amount of multimedia content, with a heavy emphasis on video.7

Any newspaper can take those steps, though each of them may require more resources than a financially strapped owner can afford. In fact, the Post is utterly unique. Bezos is unimaginably wealthy; his net worth reached nearly $91 billion in July 2017, briefly making him the world’s richest person, ahead of Microsoft founder Bill Gates.8 Then there is the Post itself—a metropolitan newspaper that throughout its history had perhaps more in common with papers like the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, and the Philadelphia Inquirer than with truly national papers like the Times and the Wall Street Journal. By virtue of its being in Washington, though, the Post is the hometown newspaper for the federal government, which automatically gives it national cachet. Taking advantage of its location, Bezos has explicitly given the Post a national mandate, resolving many years of indecision over whether the paper should place greater emphasis on national or local news. Owners of large regional newspapers elsewhere don’t have that choice—it’s already been made for them.

Still, in broad strokes, the main strategies Bezos is pursuing are applicable to any newspaper: invest in journalism and technology with the understanding that a news organization’s consumers will not pay more for less; pursue both large-scale and elite audiences, a strategy that could be called mass and class; and maintain a relentless focus on journalistic excellence.

One of the most significant milestones of the Bezos era came in October 2015, when the Post moved ahead of the New York Times in digital traffic. According to the analytics firm comScore, the Post attracted 66.9 million unique visitors that month compared with 65.8 million for the Times—a 59 percent increase for the Post over the preceding year.9 And the good news continued. In February 2016, according to comScore, the Post received 890.1 million page views, beating not just the Times (721.3 million) but the traffic monster BuzzFeed (884 million) as well. The only American news site that attracted a larger audience than the Post was CNN.com, with more than 1.4 billion page views.10 As the Year of Trump wore on, traffic at both the Post and the Times continued to increase. In October 2016, for instance, the Post surged to 99.6 million unique visitors, but came in second among newspapers, behind the Times, which attracted 104.1 million. The Post slightly outpaced the Times in total page views, by about 1.19 billion to a little less than 1.15 billion.11 By the spring of 2017, with the election over, digital traffic at both papers had dropped slightly. In April, the Times recorded nearly 89.8 million unique visitors and the Post 78.7 million. Among news sites, they were outranked only by CNN.com, with 101.2 million.12

Not surprisingly, the Post’s growth in online readership has been accompanied by a steep drop in paid print circulation. As is the case with virtually all newspapers, the Post’s print edition has shrunk substantially over the years and will almost certainly continue to do so. In September 2015, the Post reported that its weekday circulation was about 432,000—just a little more than half of its peak, 832,000, which it reached in 1993. Sunday circulation, meanwhile, slid from 881,000 in 2008 to 572,000 in September 2015.13 Given the newspaper business’s continued reliance on print for most of its revenues, the Graham family clearly would have faced a difficult challenge if the decision hadn’t been made to sell the paper.

Indeed, under Graham family ownership, the size of the Post’s newsroom had been shrinking for years. Under Bezos, it has been growing. As of March 2016, the Post employed about 700 full-time journalists, an expansion of about 140 positions. That was approximately half the number employed by the New York Times, but it was enough to allow the Post to deploy reporters both nationally and internationally to a degree that had not been possible in recent years. By the end of 2016, with readership surging and the Post reporting a profit, the paper was planning to hire perhaps as many as sixty more journalists. In addition, from the time that Bezos bought the paper through April 2015, the number of engineers working alongside journalists in the newsroom grew from four to forty-seven—a total that continued to increase over the following year.14 Those engineers were involved in a dizzying array of projects, from designing the paper’s website and apps, to building tools for infographics and database reporting, to developing an in-house content-management system and analytics dashboard.

Then there were the intangibles. Bezos had the good sense to retain Marty Baron, hired by Katharine Weymouth, the last o...