eBook - ePub

The Rise of Democracy : Revolution, War and Transformations in International Politics since 1776

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise of Democracy : Revolution, War and Transformations in International Politics since 1776

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

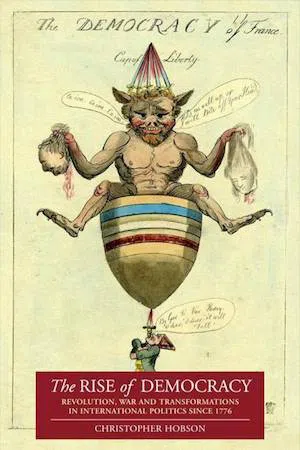

Little over 200 years ago, a quarter of a century of warfare with an 'outlaw state' brought the great powers of Europe to their knees. That state was the revolutionary democracy of France. Since then, there has been a remarkable transformation in the way democracy is understood and valued – today, it is the non-democractic states that are seen as rogue regimes. Now, Christopher Hobson explores democracy's remarkable rise from obscurity to centre stage in contemporary international relations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rise of Democracy : Revolution, War and Transformations in International Politics since 1776 by Christopher Hobson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION: BEYOND THE ‘END OF HISTORY’

We have suffered in the past from making democracy into a dogma, in the sense of thinking of it as something magical, exempt from the ordinary laws which govern human nature.

(Lindsay 1951: 7)

The exponents of liberal democracy make the mistake of ignoring the all-important fact that democracy is not something given once and for all, something as unvarying as a mathematical formula.

(Hogan 1938: 10)

INTRODUCTION

Little over 200 years ago, a quarter of a century of war fundamentally reshaped the European international order. That conflict was triggered by the advent of popular doctrines in revolutionary France, and fears that it might seek to export ‘all the wretchedness and horrors of a wild democracy’, as the British ambassador Lord Auckland described it at the time (quoted in MacLeod 1999: 44). In stark contrast, today ‘rogue regimes’ are defined by the fact that they are not democratic. In the intervening period a remarkable series of revisions took place in the way democracy was understood and valued in international society. In a relatively short space of time, popular sovereignty went from being a revolutionary and radical doctrine to becoming the foundation on which almost all states are based, while democratic government, long dismissed as archaic, unstable and completely inappropriate for modern times, came to be seen as a legitimate and desirable method of rule. This book examines these changes in the concept of democracy, and considers how these processes have interacted with the structure and functioning of international society. Put differently, this study is structured around the historical contrast between, on the one hand, the high degree of acceptance and legitimacy that democracy now holds, and on the other, the strongly negative perceptions that defined democracy when it reappeared in the late eighteenth century, which should have seemingly limited the possibilities of it becoming understood so positively.

The book seeks to throw new light on a central feature of the current international order, in which – according to Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen – democracy has become a ‘universal value’, having ‘achieved the status of being taken to be generally right’ (Sen 1999: 5). It explores the remarkable reversal that took place, accounting for democracy’s rise from obscurity to its position as a central component of state legitimacy. In contrast to the influential accounts of liberals, who too easily universalise democracy’s current meaning and suggest its ‘triumph’ was somehow inevitable, this book illustrates the opposite: just how unlikely this outcome was. Indeed, the success of these changes is reflected in the extent to which they go unquestioned today. This is hardly a new phenomenon, however. As the opening quotes from Hogan and Lindsay attest, there has been a longstanding tendency to reify, if not deify, democracy. Consequently, we often forget that its recent ascendance is not a natural or inevitable condition, but the result of political and sociological processes that have led to a certain set of ideas and institutions prevailing. In this regard, the book uses history as a resource for better understanding the contemporary challenges democracy faces, and in doing so, it develops a normative defence of democracy based on its uneven and contingent past. It reminds us that a world in which democracy is the dominant form of government is not the norm, but a historical anomaly, which in turn should promote a sense of humility.

DEMOCRACY VICTORIOUS?

When considering the standing of democracy in contemporary politics, a logical starting point is the end of the Cold War. With the collapse of the Berlin Wall, democracy was left alone and ascendant, having seen off the great twentieth-century challenges of fascism and communism. Francis Fukuyama famously heralded this as signalling the ‘end of history’, in so far as liberal democracy presented itself as the ideational endpoint for societies to move towards (Fukuyama 1989; Fukuyama 1992). While his thesis has been widely criticised for its excessive triumphalism, Fukuyama did verbalise a significant transition that was unfolding. As democratisation scholar Juan Linz noted at the time, ‘ideologically developed alternatives have discredited themselves and are exhausted leaving the field free for the democrats’ (Linz 1997: 404). In the early 1990s it certainly appeared that a new democratic era was dawning. As Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher recall, ‘the decade was marked by a strong sense of liberal democracy as a universally valid normative ideal. The remaining authoritarian regimes were in a phase of relative weakness as the tide of history appeared to be running against them’ (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014: 22). The ‘third wave’ of democratisation was reaching its peak: having traversed much of the globe from southern Europe across to Latin America and Asia, it was then spreading through eastern Europe and Africa. This represented a truly unprecedented expansion of democracy, reflecting that it had become an aspiration for people across the world and an important marker of state legitimacy.

A quarter of a century later and much of the initial bravado has since disappeared, but democracy – even if bruised and battered – remains ideationally in the ascent. Larry Diamond, a leading democratisation scholar, still regards it as being without peer: ‘no other broadly legitimate form of government exists today, and authoritarian regimes face profound challenges and contradictions that they cannot resolve without ultimately moving toward democracy’ (Diamond 2014: 8). This is reflected in the fact that few, if any, states openly repudiate the label, while most authoritarian governments tend to either claim to be democratic or suggest that they are progressing towards it (McFaul 2010: 37–41). Even China, widely seen to embody the most serious challenge to liberal democracy, does not directly deny the ideal, although it certainly does so in practice (Economist 2014a). In the speeches of world leaders, democracy is taken as a ‘natural’ state of affairs compared with the ‘distortions’ of dictatorship and other forms of authoritarian rule. Reflecting on the current state of affairs, Fukuyama’s position is now much more nuanced, but he maintains that ‘in the realm of ideas … liberal democracy still doesn’t have any real competitors. Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the ayatollahs’ Iran pay homage to democratic ideals even as they trample them in practice’ (Fukuyama 2014a).

The present ideational supremacy of democracy reflects both its institutional successes and the failures of its historic competitors. The spread of democracy across the world since the end of the Second World War is a remarkable achievement that is unlikely to suddenly disappear (Levitsky and Way 2015; Ulfelder 2015). Following the ‘third wave’ of democratisation from the 1970s through to the 1990s, and the subsequent Colour Revolutions and Arab Spring, different forms of democracies can now be found across all regions of the world. According to the most recent Freedom House report, 89 out of 195 states are considered ‘free’, collectively making up nearly 2.9 billion people or 40 percent of the world’s population (Freedom House 2015: 7). The vast majority of the world’s most stable and prosperous countries are democratic, suggesting that ‘there is a broad correlation among economic growth, social change, and the hegemony of liberal democratic ideology in the world today’ (Fukuyama 2012: 58). Democracy is seen to be uniquely capable of providing a wide range of domestic and international goods, from better protecting human rights and preventing famine, to behaving peacefully and following international law. These beliefs have helped inform the liberal ordering strategy the United States has pursued since 1945 in which the advancement of democracy has played a central role (T. Smith 1994; Ikenberry 2000).

The breadth of acceptance of democracy is further reflected in the increasingly prominent place it occupies in the programme of the United Nations (UN). While the UN may now closely align itself with democracy, this represents a marked change from the original charter, which is noticeably free of any references to it. This was updated by the 2005 World Summit outcome document, which included an explicit statement that ‘democracy is a universal value’ (United Nations General Assembly 2005: 30). It was followed by the UN secretary general’s guidance note on democracy, which proposed that

democracy, based on the rule of law, is ultimately a means to achieve international peace and security, economic and social progress and development, and respect for human rights – the three pillars of the United Nations mission as set forth in the Charter of the UN. (Ban 2009: 2)

Further examples can be found in the establishment of the UN Democracy Fund in 2005, which reflects the pivotal position that democracy now plays in post-conflict reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts, what has been dubbed the ‘New York consensus’ (Hassan and Hammond 2011: 534). These developments have been partly motivated by arguments from academics and think tanks that propose that the spread of democracy will help foster a more peaceful and prosperous international order (Parmar 2013; T. Smith 2007). Not only is democracy presented as a universal value, it is seen as having instrumental value in that it is seen to offer the best route to peace and prosperity. As such, democracy is supported and advanced for both ethical and practical reasons.

Performance legitimacy, a lack of peer competitors, and the nominal backing of the global hegemon have certainly provided strong foundations for the ideational dominance of democracy. Yet initial hopes that the end of the Cold War would mark the dawn of a new, and fundamentally better, era of international relations – defined by the spread of democracy – have failed to come to full fruition. Instead, the 1990s now appear as something of a liberal interregnum. This change of affairs has led Azar Gat to suggest that we have reached ‘the end of the end of history’ (Gat 2007). Democracy is increasingly questioned, as doubts about its normative value and institutional strength proliferate. These growing concerns have been reflected in a spate of recent books on the health of democracy and whether it is now in crisis (Coggan 2013; Dunn 2013; Kurlantzick 2013; Ringen 2013; Runciman 2013). Certainly the challenges democracy faces are manifest and they are real. A number of significant trends are pulling at the threads of democracy, threatening to slowly unravel it. The continued rise of non-democratic China, the resurgence of an increasingly authoritarian Russia, a United States weakened by political dysfunction at home and costly adventurism abroad, growing dissatisfaction and disengagement in many established democracies, the failed attempts to democratise Afghanistan and Iraq, the ‘third wave’ leading to a proliferation of ‘hybrid regimes’ rather than functioning democracies, and a growing backlash against democracy promotion efforts, are among the most obvious negative trends that are leading some to question democracy’s future.

It may seem strange to be publishing a book entitled The Rise of Democracy at a time when people are increasingly wondering if it is decline. Few can doubt that democracy’s standing has weakened since the early 1990s. This is hardly a surprise given the excessive optimism and confidence of that moment. Nonetheless, it is here that Fukuyama’s kernel of truth remains relevant: democracy still does not face a clearly defined ideological competitor in the way it previously did with fascism and communism. To date, increasing dissatisfaction with the way democracy works has manifested itself more in discontent and calls for better-functioning democracy. It has not yet led to widespread support for alternative political systems, although there is no reason to believe this cannot change. On the whole, Sheldon Wolin’s summary of the situation in 2004 remains largely accurate:

One of the most striking facts about the political world of the third millennium is the near-universal acclaim accorded democracy. It is invoked as the principal measure of legitimacy, as the standard for any new states wishing to gain entry into the comity of nations, as the justification for a pre-emptive war, and as the natural aspiration of peoples struggling anywhere for liberation from oppressive systems. Democracy has thus been given the status of a transhistorical and universal value. (Wolin 2004: 585)

This is not to deny the limitations and weaknesses of contemporary democracy, or the considerable challenges to it that presently exist, but to appreciate that there has been a remarkable consensus over its normative and political desirability in the post-Cold War world, and that the historical trend has been broadly in the direction of democracy, albeit not in any simplistic, unidirectional manner. Jørgen Møller and Svend-Erik Skaaning are ultimately justified in concluding that ‘the democratic zeitgeist, though less ebullient than … it was just after the Cold War ended, still reigns’ (Møller and Skaaning 2013: 106). In this context, what this book illustrates is that democracy is simultaneously more secure and more vulnerable than is commonly appreciated.

TOWARDS AN INTERNATIONAL HISTORY OF DEMOCRACY

Since we are all democrats (or so one may hope!), we tend to see democracy as the fulfilment of our political destiny and as the political system that will remain with us for the rest of human history. For what alternative is there to democracy?

(Ankersmit 2002: 10–11)

Is democracy’s time in the sun coming to an end? Or are the reports of its demise greatly exaggerated? It is here that returning to democracy’s past becomes such a productive and necessary exercise. On the one hand, doing so guards against a misplaced faith that democracy’s recent ascendency reflects some deeper Truth or answer to History. On the other hand, it also warns against excessive pessimism, given democracy’s remarkable resilience and its ability to provide comparatively convincing answers to some of humanity’s most challenging political questions. By returning to a time where democracy had yet to be endowed with the positive connotations that now shape it, this study seeks to counter the tendency to be ‘bewitched’ by this normatively powerful concept (Skinner 2002: 6). In this sense, it is a ‘history of the present’, which examines democracy’s past as a way of better understanding its current role in international politics and what its future may hold. Adopting such a perspective foregrounds the limitations and fragility of democracy, and cautions against the excessive confidence that has too often defined the dominant liberal account.

The book undertakes a macro-historical study of democracy’s conceptual development in modern international politics, considering how it emerged in relation to changing understandings of legitimacy and sovereignty. These principles are what help identify democracy as an international issue, as legitimacy and sovereignty are closely related phenomena that extend across and shape both the domestic and the international realms (Bukovansky 2002; Wight 1972). In considering these historically shifting and complex conceptual relationships, the study simultaneously provides a series of snapshots of the way democracy has been interpreted at different moments in time. Through examining the conceptual history of democracy, it will be seen that it has developed in close relation with the functioning of international politics (Fukuyama 2014b: 534–7). As a study by UNESCO reveals, the changing and contested nature of democracy is linked to the most basic issue that dominates the discipline of international relations (IR): ‘it is not only a problem of philosophy … it is a problem of war and peace’ (UNESCO 1951: 514).

The focus is primarily on moments of revolutionary upheaval and war, as these are times when the meanings of basic concepts undergo great change, and principles of legitimacy are challenged and revised. As Raymond Aron explains, ‘the phases of major wars – wars of religion, wars of revolution and of empire, wars of the twentieth century – have coincided with the challenging of the principle of legitimacy and of the organization of states’ (Aron 1966: 101). The study commences with the American Revolution. While clear precursors to the doctrine of popular sovereignty can be found, most notably in Britain (Morgan 1988), it was with the founding of the United States that it was explicitly introduced into, and interacted with, international politics. The majority of the study focuses on the period between the American Revolution and the end of the First World War, by which time popular sovereignty was embedded in international society, and democratic government had come to be recognised as a legitimate form of constitution. What would follow was a contest that raged until 1989, which Philip Bobbitt terms ‘the long war’, between different forms of domestic constitutions – democracy, communism and fascism – ultimately leading to the widespread acceptance of democracy as the most legitimate form of government (Bobbitt 2002). Underpinning these observations, and the book as a whole, is a conception of international society, as questions about legitimate forms of statehood and domestic governance, which frame much of this investigation, only make sense within some kind of interpretative community where shared assumptions, norms and beliefs exist. These theoretical assumptions are outlined in more detail in the next chapter.

In considering democracy’s conceptual development, it can be seen that historically democracy has meant two things: a form of state, what is commonly referred to as popular sovereignty, and a form of government, a set of domestic governing institutions, how democracy is now generally understood. Employing Kant’s distinction between forma imperii (state form) and forma regiminis (government form), it is argued that to properly appreciate democracy’s conceptual development and emergence in international society both meanings must be tracked. In ancient Greece, where the origins of modern democracy lie, dēmokratia was a direct form of rule where the people both constituted the polity and exercised power. Popular sovereignty and democratic rule existed together. When democracy reappeared in modern politics, these two dimensions were disaggregated. Popular sovereignty was separate from democratic institutions, and preceded it. The former was able to receive far greater and quicker acceptance in international society because it was more limited: the location of sovereignty was challenged, but its nature was left untouched. Furthermore, popular sovereignty did not necessarily entail a certain set of domestic institutions: it may point towards democracy, but it need not. One need only recall Hobbes’s theory or the fascist regimes of the twentieth century for important examples of where consent-based notions of sovereignty did not entail popular rule. As a form of government, democracy struggled against a diachronic structure that strongly advised against it. Nonetheless, through a series of conceptual revisions, ridding it of the negative connotations that had plagued it for so long, democracy came to be regarded as a legitimate form of domestic constitution. Once this occurred, the nature of the contestation shifted, with much of the twentieth century being defined by a battle between different domestic regime types. With communism following fascism into the dustbin of history, democracy was left standing alone at the end of the twentieth century, but most of the conceptual innovations that laid the foundations for this outcome had finished being laid almost a century earlier.

The account provided is one that emphasises the historical contingency of democracy, deta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Beyond the ‘End of History’

- 2 Thucydidean Themes: Democracy in International Relations

- 3 Fear and Faith: The Founding of the United States

- 4 The Crucible of Democracy: The French Revolution

- 5 Reaction, Revolution and Empire: The Nineteenth Century

- 6 The Wilsonian Revolution: World War One

- 7 From the Brink to ‘Triumph’: The Twentieth Century

- 8 Conclusion: Democracy and Humility

- Bibliography

- Index