- 574 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theory of Transformations in Steels

About this book

Written by the leading authority in the field of solid-state phase transformations, Theory of Transformations in Steels is the first book to provide readers with a complete discussion of the theory of transformations in steel.

- Offers comprehensive treatment of solid-state transformations, covering the vast number in steels

- Serves as a single source for almost any aspect of the subject

- Features discussion of physical properties, thermodynamics, diffusion, and kinetics

- Covers ferrites, martensite, cementite, carbides, nitrides, substitutionally-alloyed precipitates, and pearlite

- Contains a thoroughly researched and comprehensive list of references as further and recommended reading

With its broad and deep coverage of the subject, this work aims at inspiring research within the field of materials science and metallurgy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1Crystal structures and mechanisms

1.1 Allotropes of Iron

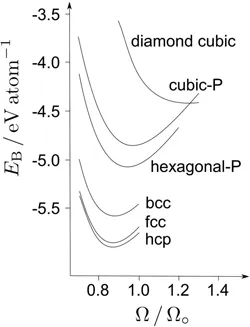

Why do metals adopt the crystal structures that they do? This no longer is a curiosity because the metallic state is so well understood that it is possible to select, from a calculation of the cohesive energies of trial structures, that which should be the most stable. Figure 1.1 shows the cohesive energy as a function of the density and crystal structure. Of all the test structures, hexagonal close-packed (hcp) iron is found to have the highest cohesion and therefore should represent the most stable form. This contradicts experience, but the calculations do not account for the ferromagnetism of body-centred cubic iron (ferrite), which would make it more stable than the hcp form. There are in fact magnetic transitions in each of the allotropes of iron, details of which are reserved for Chapter 2.

Figure 1.1 Plot of cohesive energy for 0K and 0Pa pressure versus the normalised volume per atom for a variety of crystal structures of iron. is the binding energy per atom in the crystal relative to that of a free atom. Hexagonal-P and Cubic-P are primitive structures; like the diamond cubic form, they do not exist on earth. Adapted with permission from [1]. Copyrighted by the American Physical Society.

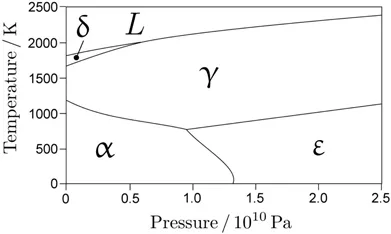

Only three allotropes of iron occur in nature, in bulk form; Figure 1.2 shows the phase diagram for pure iron. Each point on a boundary between the phase fields represents an equilibrium state in which two phases can coexist. The triple point where the three boundaries intersect represents an equilibrium between all three co-existing phases. It is seen that in pure iron, the hexagonal close-packed form is stable only at high pressures, consistent with its high density.

There are two further allotropes which can be created in the form of thin films. Face-centred tetragonal iron can be prepared by coherently depositing iron as a thin film on a plane of a substrate such as copper with which the iron has a mismatch. The atoms in the first deposited layer replicate the positions of those on the substrate. A few monolayers can be forced into coherency in the plane of the substrate with a corresponding distortion normal to the substrate. This gives the deposit a face-centred tetragonal structure which in the absence of any mismatch would be face-centred cubic [2, 3]. Eventually, as the film thickens during the deposition process to beyond about ten monolayers (on copper), the structure relaxes to the low-energy bcc form, a process accompanied by the formation of dislocation defects which accommodate the misfit with the substrate.

Growing iron on a misfitting surface of a face-centred cubic substrate similarly causes a distortion along the surface normal, giving trigonal iron [4].1 Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms that has a hexagonal structure with a lattice parameter of 0.245nm. The crystal is seldom perfect, often containing holes. Compounds used in its manufacture provide a source of iron atoms that can attach themselves to the edges of these holes, building up into monoatomic layers that are suspended in the graphene films. These “free-standing” single-atom-thick two-dimensional arrays of iron form a square lattice with a parameter 0.265 nm [5]. This particular structure has been suggested to be a consequence of lattice matching with the “armchair” configuration of carbon atoms at the graphene edges where the bonding between the iron and carbon atoms is stronger than when the iron attaches to the “zig-zag” edges of the graphene [5]. The largest stable monolayer of iron on holes in graphene is found to be about 3nm2 in area.

Figure 1.2 Temperature versus pressure equilibrium phase diagram for pure iron, based on assessed thermodynamic data. The triple point temperature and pressure are 490∘C and 11GPa respectively. , and refer to ferrite, austenite and -iron respectively. δ is simply the higher temperature designation of . Diagram courtesy of Shaumik Lenka, calculated using the database ‘TCFE8’, and ThermoCalc version 2015b.

Table 1.1 lists some transformation temperatures and thermodynamic data for the natural allotropes of iron. The free energy changes during the solid-state transformations are really quite small, even when compared with the energy associated with the magnetic disordering of ferrite. In a way, this is a reflection of the fact that their crystal structures are not all that different (Figure 1.3). For example, assuming a hard-sphere model, the crystal structure of austenite and -iron can be generated by stacking close-packed layers of iron atoms in such a way that each successive layer sits in the depressions of the underlying layer. There are in each layer, two types of depressions, so the close-packed layers can be stacked either in the sequence or . The former sequence, which has a stacking period of three, generates the austenite structure, whereas the latter gives the hcp structure of -iron with a stacking period of two. The best comparison of the relative densities of the phases is made at the triple point where the allotropes are in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Author

- Acronyms etc.

- Nomenclature

- Chapter 1 Crystal structures and mechanisms

- Chapter 2 Thermodynamics

- Chapter 3 Diffusion

- Chapter 4 Ferrite by reconstructive transformation

- Chapter 5 Martensite

- Chapter 6 Bainite

- Chapter 7 Widmanstätten ferrite

- Chapter 8 Cementite

- Chapter 9 Other Fe-C carbides

- Chapter 10 Nitrides

- Chapter 11 Substitutionally alloyed precipitates

- Chapter 12 Pearlite

- Chapter 13 Aspects of kinetic theory

- Author index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Theory of Transformations in Steels by Harshad K. D. H. Bhadeshia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Mechanics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.