![]()

Part 1

Why the Purpose Gap?

Razor wire covers the horizon

I can see the wire cutters

To find a way through

A journey said to be impossible

I would need to bleed.

To get to the other side

Cut the wire

Hold open the small hole

To help others pass without incident

To collectively remove the horizon

Returning a landscape

Removing artificial barriers

To its natural wonder

And finding freedom.

![]()

Chapter 1

Conditions

Daring to Dream

In 2018, between May and the end of June, more than 2,300 children were separated from their families at the U.S. border.1 Family separation was not the act of a few bad politicians. It was an explicit U.S. strategy described as deterrence—the same strategy the military uses, where the punishment of certain actions will be so severe that people choose not to engage in them. The message is clear: If you come here with your family, we will break your family, break your spirit, break your will to find meaning and purpose in this country. Children have been held behind chain-link fences and, in one case, under a bridge,2 sleeping on concrete floors away from their families. All of this is punishment for wanting a better life and daring to seek it out. The purpose of these families’ journey, of bringing these innocent children on it, was to find a better life among us, their neighbors. And in response we stole their lives and purpose. Brown Latinx/o/a and Latin American children, like my family, have been denied a life of flourishing. In fact, we are collectively and actively deterring them from pursuing their purpose.

I watched the news like the rest of the country, witnessing pastors and faith leaders, many of them my friends and colleagues, go to play, pray, worship, and break bread with those on both sides of the border. Not one of those nights did I sleep with dry eyes. Their sacrifice, their faith, and their love for their children were not unlike my own. Gilberto Ramos, a fifteen-year-old boy, travelled to the United States to get his mother’s epilepsy medicine and find a better life. He was found dead in the Texas desert, recognizable by the white rosary that his mother draped around his neck and a phone number written on his belt.3 What separated these young people from my own family’s experience was the distance of just a few generations on this side of the border.

When I was in seminary, I spent time offering spiritual care visiting adults who were awaiting deportation, often separated from their families, and even more tragically, whose families did not know their location. When I arrived at the facility, I would sit in the parking lot, praying to God for strength because I felt personally responsible for stealing their many purposes. I gripped my own rosary, a gift from my grandma that I still carry with me. These were my friends who had hopes and dreams for themselves and their children, who came here to close the purpose gap for their own children. Their children’s view of the world would be shaped by this harrowing violence.

There is a program in my hometown of Salinas, California, where a local pastor and priest take children to federal prisons all over the state to visit their incarcerated parents. These children get to “play” with their parents under armed guard and in view of razor-wire fences. How can these young people imagine their purpose in life? For Black and Brown children across this country, we have stolen the purpose of the next generation. The children look lovingly at their parents. Happiness overflows when these young people reunite with their family members. Accompanying this meeting is a guard with a shotgun in hand, ugly physical barriers, and the volunteer who was their sole means of seeing their loved one. Can anyone doubt that this scene will forever shape that child’s imagination about what is possible? American adults have declared war on America’s children, committing violence over the question of who has a purpose and who does not. The denial of the sacredness of every child is a sin we have committed collectively. To close the purpose gap for all children and people on this planet requires that we repent and undo the systems that judge some lives worthy of freedom and others not.

Those who do not see their connection to these young people caged like animals are blind to the oppression and violence committed against Black and Brown children. Those who say, “They are not my children,” “It is not my problem,” or “My community has our own problems,” are traumatizing their own children as well. It is a moral injury that will last for generations. Those who choose to break the cycles of violence will look back at this generation and say, “I can’t believe my family let that happen.”

Others of us can neither ignore nor explain away this trauma because we live it. We inherit this generational trauma. We feel in our bones and our skin the attempted genocide of indigenous people on this continent and Jewish people on another, the violence of apartheid and slavery, the lasting effects of Jim Crow, and the abuse and murder of generations of Black bodies through policing and mass incarceration. They are the sum of our history, which creates horizons within which there is no imagining a better world, only surviving this one.

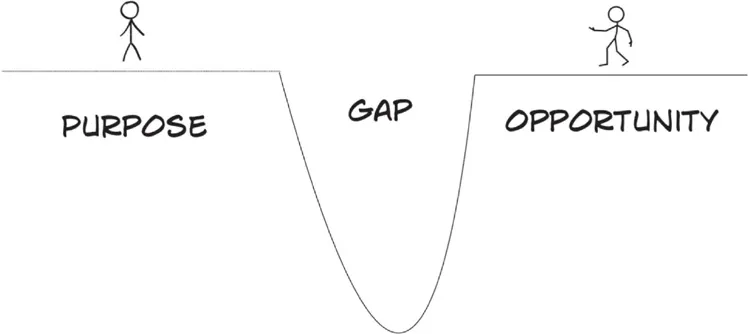

When our children are not free to imagine, they live in fear of the future. There is no celebration of their potential. On a drive home from an extracurricular activity, my son said to me, “I wish I wasn’t Latino because then I would be safe.” Parents, educators, social workers, and pastors alike remind children that we love them, not just because it is the right thing to do, but because the world sends these innocent children the opposite message. We have to be realistic about the ways our children of color behave in a certain way around police, to explain the violence against other children who look like them, and to prepare them for a world that has tried to eradicate or enslave them. Closing the purpose gap is about these conversations. These are conversations about purpose and meaning. What does it mean to discern purpose as a person of color? Does God call us to live a life of meaning and purpose? Does God allow us to imagine lives beyond the cages designed to capture our dreams, to snatch our lives’ many purposes, to incarcerate our imagination about our own self-worth? This is what we mean by the term “purpose gap.” There is a deep chasm between the children who get to dream freely and the children whose purpose must be shaped within a nightmare, between Pharaoh and Pilate on the one hand, and Moses and Jesus on the other, tattooed by death even before coming into this world.

There are truths that our collective bodies know and hold. A pain expressed in a word, a shout, a whisper, a hand gesture, or a look that does not need translation. Closing the purpose gap is about working through and exploring the wisdom and practices from our communities that might give the next generation a chance to dream with less fear and to dream of the realization of freedom. For example, I work at home with my children using a mixture of practices that deepen their sense of self. This work is accompanied by the ancestors, the community, and, of course, their parents, who love them beyond all things. I teach my children how to perform rituals, say prayers, and practice traditions that have been handed down over generations to ensure their survival and connect them to the above and beyond.

As I outlined in the introduction, intimate moments with our own communities and in spaces designed for our thriving do exist. They include neighborhood playgrounds, fields, worship spaces, historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, tribal colleges, and the like. Yet with these exceptions, we largely spend our time responding to dominant white, Anglo, Protestant, patriarchal, cis-gendered, able-bodied, neuro-homogenous, heteronormative, and anthropocentric categories of existence. A gap exists between the dominant culture’s ability to create meaning and purpose and my own. A misperception confronts us, saying that the only knowledge creators are the descendants of the dominating, colonizing, and violent forces. To assert our wisdom and knowledge, especially to say that our lives are divine and equal, is to demand life in the face of death. There will be resistance. If we are to liberate ourselves, we must demand our freedom and the right to dream, the right to have a purpose in this lifetime.

We have constructed and designed worlds around this myth of white supremacy and Western superiority. It is as though our society is part of a science fiction novel in which the author created a world reflective solely of his own white, male experience. Not a single day goes by in which whiteness, patriarchy, and colonization do not affect my life. In the grocery store, labels in the produce section provide a helpful reminder that people like me plant and harvest the food while privileged white families reap the benefits. From the dishes, to the coffee, to the clothes, the cars, the roads, the buildings, the systems and structures, rules and regulations, laws and legal structures—within all of these I will, at some point in my day, encounter whiteness as it subjugates, oppresses, and celebrates its victory. There is no denying it exists, because it surrounds us.

On the other hand, we exist everywhere too. The wisdom of my ancestors guides me and leads me. The love of our tías, mothers, and abuelas guides us to lives of meaning and purpose. Their example proves why I need to author this book in a hue, a tone, and a color that reflects the love of the divine. Next time someone of my hue or tone, or our brothers and sisters, primos and primas, look for literature to help find meaning and purpose, they will have in this book something that reflects both their reality and their beauty. If, as I have argued elsewhere,4 vocation is the call to life, then I claim here that external conditions have as much to do with one finding one’s purpose as does one’s internal discernment. To understand the purpose gap, one need only the vocational literature, the theology of vocation, and the self-help genre to see it was not intended for us.

Those from marginalized and minoritized communities must begin with our material reality. White, upper-middle-class scholars typically author works in the fields of vocation, meaning, purpose, and related disciplines in self-help and psychological well-being. That is not to say that the writing coming from my colleagues Dorothy Bass,5 David Cunningham,6 Kathleen Cahalan,7 Dori Baker and Joyce Mercer,8 Diana Butler Bass,9 Parker Palmer,10 and David Brooks,11 or the great collection William Placher12 pulled together in exploring the vocational writings of Martin Luther, George Fox, Walter Rauschenbusch, Søren Kierkegaard, and the like, are necessarily wrong or bad. It does not mean that we cannot go back to definitions as set forth by Thomas Merton,13 Dorothy Day,14 or the like. It is not to dismiss Rick Warren’s popular The Purpose Driven Life, because there is deep value in knowing that our purpose exists beyond our own desires. However, when Warren writes, “You were made of God, not vice versa, and life is about letting God use you for his purposes, not your using him for your own purpose,” I cringe.15 For young children of color who are locked up against their will, whose lives are cut short, who never have a shot, this was not God’s nor should be society’s plan for the innocent. They should not be used and abused. Suffering children are not in God’s plan, and if it is, that is not a God worth believing in.

White authors write from a particular place that could not be farther from the fields in which I grew up, a fact none of them would argue, for the backgrounds and cultural vantage points of white authors often go unaccounted. In a slightly comical story, I was set to present with several scholars on the topic of meaning. One of them, a preeminent scholar and middle-aged white woman, asked me what I was going to talk about. I told her about my work on meaning and purpose. She asked if I knew her work and the work of one of her friends, emphasizing that they are both well known. I responded, “Of course. In my research, I make sure to look at people doing similar work.” And after a slight pause I added, “Do you think you and your friend know my work?”

Without hesitation her response was “No.” However, she knew the work of all the other presenters that night, two white scholars who did nothing in our shared field of study. I am not saying that everyone must know my work, but the assumption of power was clear. I was supposed to know her and her friend’s work, but they do not have to be curious or even think twice about what is appearing in their own discipline from my community. Their work is the standard, and mine is only a niche, a particularity, a margin to the center.

Even in the best-case scenario, authors from majority cultures qualify their writings with a level of awareness, saying something like, “I want to recognize my privilege. My white, cis-gendered, middle-class, heteronormative, and educated background informs how I write and think.” Sometimes they will add something like, “. . . who writes from stolen land and recognizing that I benefit from years of oppression to communities of color.” Without missing a beat, they all seem to go on to re-create the same power dynamics in their writing that they had set out to dismantle with their recognition of power and privilege. As Jennifer Harvey writes in Raising White Kids, it is not just about acknowledging difference; it is about being race-conscious enough to undo and dismantle the very systems that create the purpose gap between white children and everyone else.16 If you have the power to acknowledge white privilege, you have the power to dismantle white supremacy. The distance between the tw...