![]()

1

Introduction: Roman and Medieval Exeter and their Hinterlands – From Isca to Excester

Stephen Rippon and Neil Holbrook

Towns and their hinterlands

Today, we see the diverse character of the British landscape as one of its most treasured features. Britain’s richly varied geology, topography and soils have combined with its pivotal location on Europe’s western seaboard, and a complex history of invasions and migrations, to create a series of countrysides and townscapes whose character vary enormously from region to region. Exeter lies at the heart of one of the most distinctive landscapes in Britain – the South-West Peninsula – although its location (remote from London) and the character of its archaeological record (that does not conform to that seen across much of lowland Britain) has led many to regard it in less than positive terms. The eminent Romanist Francis Haverfield, for example, suggested that Exeter was an ‘outpost of Romanization in the far west’, and that the territory west of the River Exe ‘presented none of the normal features of Romano-British life’ (Haverfield 1924a, 214; 1924b, 2). It certainly is true that neither Exeter nor the countryside around it looked much like London and the South-East during the Roman period, but was this because the region was backward and poorly developed, or a reflection of how the communities living there chose to adopt subtly different identities compared to those in South-East Britain? Although Romanists were somewhat slow to recognise and understand the diversity that is evident within the landscapes of Britain, this is thankfully now changing (e.g. Mattingly 2006; Rippon 2008a; 2012a; Smith et al. 2016) with the regional boundaries that are starting to emerge being remarkably similar to those that have long been recognised during the medieval period (Gray 1915; Rackham 1986; Roberts and Wrathmell 2000; 2002; Rippon et al. 2015; Rippon 2018a).

The development of urban centres was crucial to the wider social and economic character of any region, and the evolution of a town can only be understood within the context of its wider landscape. Urban centres were on the whole agriculturally non-productive settlements, although Domesday records that Exeter’s burgesses had land for 12 ploughteams extra civitatem [outside the city] suggesting that a large area of arable – perhaps over a thousand acres – was cultivated by people living there (Allan et al. 1984, 406). In the well-documented medieval period we know that towns will have had a variety of hinterlands ranging from the immediately adjacent countryside that produced food consumed by the townsfolk and the raw materials used by its craftsmen, through to more distant places with which its merchants traded. These different urban hinterlands can be thought of as a series of zones that surrounded a town, although variations in topography, ease of communication, and a wide range of socio-economic factors will have led these zones to be rather irregular in shape. The innermost hinterland was the local area that both supplied a town with its day-to-day needs, and to which in turn the town provided basic services. This inner hinterland is likely to be the area of a day’s walk from the town, something that in the case of medieval Exeter is borne out by a variety of documentary sources (Kowaleski 1995). In the medieval period at least Exeter was, however, part of a hierarchy of towns that included a series of smaller centres about 20 km away, and for their day-to-day needs people living more than 10 km from Exeter will probably have visited one of those other local markets for goods and services that were in regular demand.

There were, however, more specialised items that people required far less frequently such that only a major town – with a regional-scale catchment – would generate sufficient custom for a trader to be able to make a living. In the case of Exeter this included precious metal working – there is still a road called Goldsmith Street – as well as being a regional centre for services such as secular and ecclesiastical administration. Exeter’s international significance started when it was a Roman legionary fortress that, along with its port at Topsham, was part of an important trade route for goods from mainland Europe that were supplied to the army in western Britain. Exeter was refounded as a civilian town (Isca Dumnoniorum) whereupon it became the largest settlement in the South-West Peninsula, although the extent to which it functioned as a town in the medieval sense will need further discussion (see Chapters 6 and 9). Following a period of post-Roman desertion that was common to most British towns, the revival of urbanism in Escanceaster (as Exeter was described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) saw it rapidly re-establish itself in the 10th century as a town of regional standing, with an important mint and ceramic assemblages suggesting that international trade had resumed by the early 10th century.

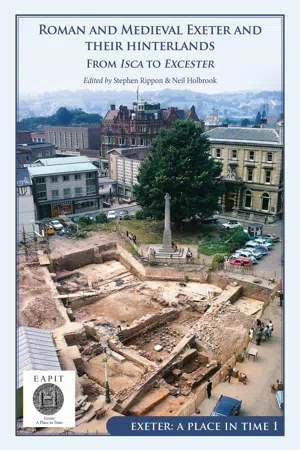

The need to study Exeter in the wider context of its multiple hinterlands was a major theme of the Exeter: A Place in Time project (EAPIT), and as such this book is about not just Exeter but the South-West region generally (Fig. 1.1). Exeter, and the wider South-West, provide a particularly distinctive area to study due to their liminality within both Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England, yet they have seen far less archaeological research than many other parts of Britain (both before and after the routine introduction of development-led archaeology in 1990). Exeter and the South-West do, however, possess great potential for research. The large backlog of unpublished excavations within the city, alongside the extensive collections of artefacts in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) – much already catalogued and published (Allan 1984a; Holbrook and Bidwell 1991; 1992) – provide an excellent opportunity for new work to be carried out, and in particular for the application of modern scientific techniques. The geologically varied landscape of the South-West also makes it ideal for the use of stable isotope (EAPIT 1, Chapters 3 and 4) and petrological analysis of pottery (EAPIT 2, Chapters 12, 17 and 18) and tile (EAPIT 2, Chapter 13).

Exeter is located at the head of the Exe Estuary, one of the major sheltered tidal inlets on Britain’s South-West coast (Figs 1.1 and 1.2). It was located at the river’s lowest crossing point (using bridge-building technology available in both the Roman and medieval periods), although there were fording-places further downstream such as at Countess Weir (where an 18th-century bridge now stands). Although the river may have been navigable by small boats as far upstream as Exeter, its main port in both the Roman and medieval periods was established downstream at Topsham. Exeter’s immediate hinterland was the agriculturally rich farmland of the Eastern Devon Lowlands – sometimes called ‘Red Devon’ due to the colour of its soils – that also provided iron-rich clays that were used for making pottery and tiles. The South-West Peninsula also has a range of other minerals that at various times were crucial to the economy of Exeter, such as the Blackdown Hills – c. 30 km to the east of the city – that supported another important pottery industry as well as the production of iron and quern stones. To the west of Exeter lay the granite uplands of Dartmoor and Cornwall that were rich in a range of metals, most notably tin, lead and silver, that were also exploited during the Roman and medieval periods, as well as being a source of summer grazing.

Whilst Exeter’s location was ideal for exploiting these rich natural resources, as well as engaging in international trade, it was often liminal to the places of power, wealth and cultural ...