eBook - ePub

Rubens's Spirit

From Ingenuity to Genius

Alexander Marr

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rubens's Spirit

From Ingenuity to Genius

Alexander Marr

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Peter Paul Rubens was the most inventive and prolific northern European artist of his age. This book discusses his life and work in relation to three interrelated themes: spirit, ingenuity, and genius. It argues that Rubens and his reception were pivotal in the transformation of early modern ingenuity into Romantic genius. Ranging across the artist's entire career, it explores Rubens's engagement with these themes in his art and life. Alexander Marr looks at Rubens's forays into altarpiece painting in Italy as well as his collaborations with fellow artists in his hometown of Antwerp, and his complex relationship with the spirit of pleasure. It concludes with his late landscapes in connection to genius loci, the spirit of the place.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Rubens's Spirit by Alexander Marr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art GeneralONE

Holy Spirit

You find Rubens’s women too fleshy? I tell you, they were his women, and if he had populated heaven and hell, air, earth and water with ideal forms, he would have been a poor husband and they would not have been the mighty flesh of his flesh and bone of his bone.1

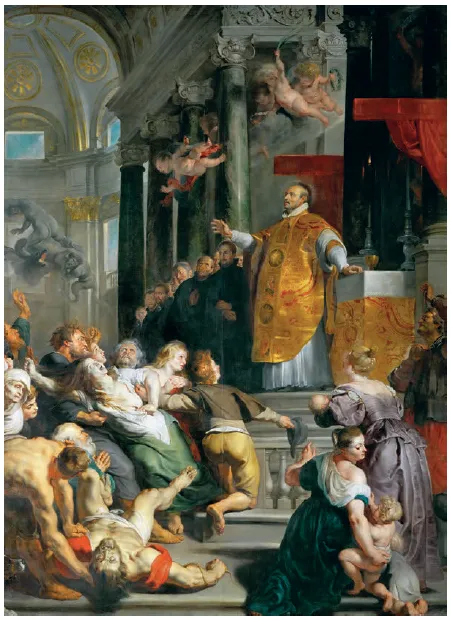

Yet Rubens made his name not as a painter of flesh but as a painter of spirit, or rather of bodies being moved by thespirit. In his early years as a mature artist – first in Italy, then back home in Antwerp – Rubens produced a series of devotional works that depict the faithful in a moment of being touched, filled or moved by the Holy Spirit. St Gregory the Great Surrounded by Other Saints (1606–7), commissioned by the Oratorians for the high altarpiece of the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella), their main church in Rome, is a good example (illus. 10). The saint – his arms open to receive celestial light into his body – is moved to ecstasy by the Holy Spirit, which descends in the form of a dove, its wing touching his brow. In this picture, Rubens traded on the productive ambiguity of spiritus (pneuma, in Greek) as something that hovers between the material and the immaterial. As Thomas Aquinas explained, ‘“spirit” is a name imposed to signify the subtlety of some nature. Hence it is said of corporeal as well as incorporeal things.’2 In theology, spiritus was the stuff of the soul and of God, properly imperceptible yet made visible in miracles and visions, depicted often as the most intangible substances: vapours, light and fire. In natural philosophy and medicine, spiritus was a subtle substance, which had both a simple and a rarefied form: the ‘vital’ and ‘animal’ spirits. In its purest form, in the ventricles of the brain, the animal spirits powered cognition. Mingled with blood, the vital spirits coursed through the body, enabling motion and sensation. The Spanish physician Juan Huarte de San Juan explained this succinctly in his influential treatise on ingenuity, Examen de ingenios para las ciencias (1575):

9 Peter Paul Rubens, The Three Graces, c. 1630–35, oil on panel.

10 Peter Paul Rubens, St Gregory the Great Surrounded by other Saints, 1606–7, oil on canvas.

there is found in the body another substance, whose service the reasonable soul useth in his operations . . . These are the vitall spirits, and arteriall blood, which go wandring through the whole body, and remaine evermore united to the imagination, following his contemplation. The office of this spirituall substance is, to stir up the powers of man, and to give them force and vigour that they may be able to work.3

In Rubens’s picture, St Gregory’s mind and body – both driven by natural spirits – have been moved by the spirit, the Holy Spirit. The painting’s original viewers, the congregants of the Chiesa Nuova, were expected similarly to be ‘spiritually moved’ by Rubens’s painting while admiring equally the artist’s own creative talents in the work. Indeed, we may say that in Rubens the Counter-Reformation Church found an ideal partner through a felicitous meeting of spirits: an artist equipped with the natural ingenium and religious sympathy to realize most effectively the ambitions of a faith in renewal.

Faith surely aided his phenomenal success in securing commissions for religious paintings from Catholic patrons. While the artist’s father had converted to Protestantism, Rubens’s mother raised her children as Catholics in Antwerp, in an environment that strongly encouraged conformity to the Roman faith. Rubens is generally considered to be the artistic embodiment of this conformity, yet in fact we know very little about his personal religious convictions. His correspondence contains barely a mention of confessional matters beyond transactions for paintings with religious subjectmatter, while hardly any reports of his devotional habits have come down to us. A rare glimpse is provided by Roger de Piles, who portrayed Rubens as firmly devout, writing that the artist ‘rose every day at four in the morning and made it a rule to start the day with Mass’.4 If true (and there is no reason to doubt de Piles, who had conferred with Rubens’s nephew Philip), such observance doubtless recommended the artist to patrons such as the Oratorians and the Jesuits, committed to renewing, strengthening and spreading Catholicism in Europe and beyond by commissioning robust imagery ofmartyrdom and miracles. These included Rubens’s paintings for the Jesuit church in Antwerp, among which were an enormous pair of altarpieces proclaiming the spiritual efficacy of the order’s founders: The Miracles of Francis Xavier and The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola (both c. 1617–18) (illus. 11).5 In the latter, Rubens depicted Ignatius as a thaumaturge, a spiritual wonderworker. He conducts the spiritus – depicted as a gauzy plume of vapour – emanating from an altarpiece of The Crucifixion in order to drive out demons from possessed bodies, writhing furiously in the foreground. This unashamedly propagandistic picture is a useful reminder that in his commissions for altarpieces and other devotional works, Rubens accommodated himself to the doctrinal or political positions of his patrons. That is to say, his commissioned pictures reflect the patrons’ attitudes, not necessarily the artist’s own, even if these may often have been in accord.

11 Peter Paul Rubens, The Miracles of St Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1617–18, oil on panel.

St Gregory the Great Surrounded by Other Saints was one of Rubens’s first major commissions for a religious work during his Italian period, a great coup for an enterprising artist seeking to make his name. The Counter-Reformation world of the Catholic nations was a fertile environment for his ambitions. The promulgation of the decrees of the Council of Trent (1545–63), the rise of religious orders such as the Jesuits (with whom Rubens developed a close relationship in Italy and Antwerp), and the desire of ecclesiastical and secular authorities to promote orthodox worship led to a rash of new commissions for devotional works, both public and private. Rubens’s journey to Italy was devised in part to take advantage of these opportunities, as well as to steep himself in the archaeology of the classical past and to see at first hand the works of the most renowned modern artists. Having completed his artistic training and established himself as a master in Antwerp, Rubens set off for Italy in the spring of 1600, travelling with an apprentice, Deodaat del Monte. He made his way directly to Venice, determined to study paintings by the celebrated exponents of colorito: Titian, Veronese and Tintoretto. Shortly thereafter, he entered the service of Vincenzo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, dividing his time between Mantua, Genoa (where he compiled material for a short, illustrated book of the city’s architecture, the Palazzi di Genova, published in 1622) and Rome. In 1603 Rubens was entrusted with a diplomatic mission to Spain for his Mantuan patron, which afforded him a valuable opportunity to see the Spanish royal collections. As he wrote to Annibale Chieppio, an agent of the Gonzaga, he had seen ‘many splendid works of Titian, of Raphael, and others, which have astonished me, both by their quality and quantity, in the King’s palace, in the Escorial, and elsewhere’.6

Although Rubens received a handful of commissions for religious paintings, his first few years in Italy and Spain were mainly spent painting portraits of his patrons and associated noble families.7 Frustrated by what he considered to be employment unequal to his worth, Rubens longed for better commissions: of history paintings in general, but especially of altarpieces – the touchstone of success. As he wrote to Chieppio in late 1603:

The pretext of the portraits, even though a humble one, would satisfy me as an introduction to greater things . . . I should not have to waste more time, travel, expenses, salaries . . . upon works unworthy of me, and which anyone can do to the Duke’s taste . . . I beg him earnestly to employ me, at home or abroad, in works more appropriate to my talent [al genio mio].8

By invoking his genio, Rubens implied both that his abilities were better suited to history painting and that he felt naturally inclined towards a grander, more elevated kind of painting than humble portraiture.

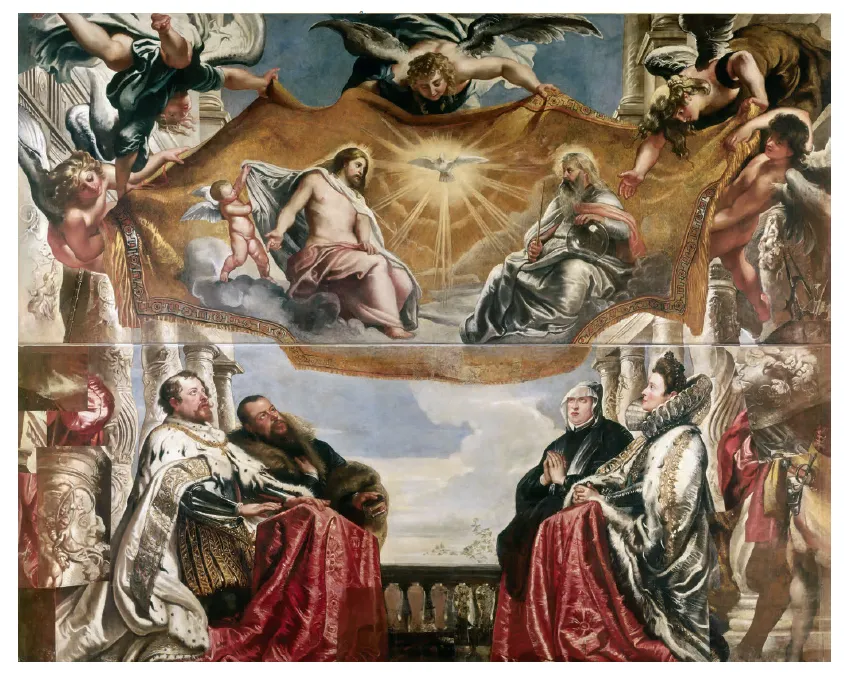

His wish was soon granted. At the beginning of 1604, Rubens was commissioned to paint three large works as part of a frieze to decorate the principal chapel of the Jesuit church in Mantua. Since this church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, that was the subject of the main painting – The Holy Trinity Adored by the Duke of Mantua and His Family (otherwise known as The Gonzaga Adoration) – accompanied by The Transfiguration and The Baptism of Christ, all of which were completed by 1605 (illus. 12). The main altarpiece, dismembered during the Napoleonic Wars, is indebted in both its palette and treatment of votive subject-matter to the Venetian tradition – Titian’s Vendramin Family Adoring the Cross (c. 1540–45), for example. Indeed, Rubens’s composition of the three members of the Trinity is likely modelled on Titian’s La Gloria (1554), painted for Charles V, which Rubens saw in the Escorial. Despite these precedents, Rubens depicted the Gonzaga family’s vision of the Trinity with considerable originality: as figures on a billowing tapestry, held aloft by angels against the backdrop of a colonnade of twisting, Solomonic columns.9 The rapt members of the noble house (the duke and his wife, accompanied by his deceased parents) who kneel inadoration below thus witness a vision of the Trinity as a work of art: a miraculous artifice, woven from thread of celestial gold. Conventionally, only saints and the blessed dead are granted heavenly visions. By adding the duke’s dead parents to the devotees, Rubens overcame the theological problem of depicting still-living worshippers witnessing a vision. The ambiguous nature of the tapestry as both art object and vision aided this ingenious solution.

overleaf: 12 Peter Paul Rubens, The Holy Trinity Adored by the Duke of Mantua and His Family, also known as The Gonzaga Adorat...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Series Editor

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Holy Spirit

- 2 Vive l’Esprit

- 3 Vital Spirits

- 4 Genial Painting

- Conclusion: Genius Loci

- REFERENCES

- FURTHER READING

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INDEX