![]()

Part I

The Residential Years, 1958–67

![]()

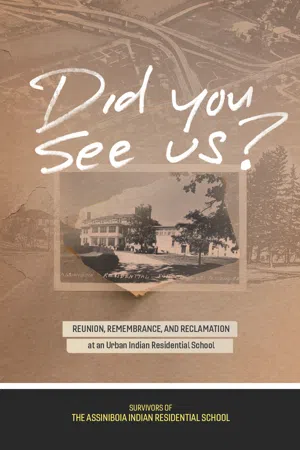

Figure 1. Assiniboia Indian Residential School, c. 1950–70.

When the Survivor advisors for the project were approached about how the book should be organized, they were clear that remembrances should be presented in chronological order. Every year of students had their own distinct experience of Assiniboia, but the differences are most apparent between those who attended Assiniboia as a residential school and those who were hostelled there and ferried off to non-Indigenous high schools for their education. Each group faced their own challenges, and each found their own ways to survive and even thrive in their particular era.

The remembrances that follow begin with those of Survivors who were there when the school opened. They feature recollections of staff members and interactions with the settler community beyond the school. As the school enters the 1960s, remembrances turn toward sporting successes, student relationships, and, on occasion, a bit of mischief. In 1967, under a policy of integration, students are no longer educated within the Assiniboia classrooms building; instead, they attend Winnipeg high schools such as Kelvin, Grant Park, and Saint Mary’s. Assiniboia provides us a unique opportunity, given its relatively short lifespan, to hear from Survivors from its opening until its close. The same is often not possible for Indian residential schools that operated from the late 1800s, or even early 1900s, into the late twentieth century.

![]()

We All Got Along and Treated Each Other With Kindness and Respect

Dorothy-Ann Crate (née James)

Manto Sakikan – God’s Lake First Nation, Manitoba1

Attended Assiniboia, 1958–62

In 1958–59, Assiniboia Indian Residential School on 621 Academy Road in Winnipeg was the first residential high school in the province of Manitoba.

Most of us students were transferred from Fort Alexander Indian Residential School, situated on the Sagkeeng First Nation along the Winnipeg River. That school provided classes only up to grade eight.

There were ninety-eight young girls and boys who started at Assiniboia Indian Residential School in the district of River Heights on the west side of Winnipeg, towards the Tuxedo Area.

The principal at Fort Alexander, Father Bilodeau, or any other administrative person, had never told us early in the year that we were going to be transferred to Winnipeg.

Students from Fort Alexander were not too anxious to move to Winnipeg, as most of them had their families living at the Fort Alexander Reserve (Sagkeeng). But for the students from northern Manitoba, we were overwhelmingly excited to get to know the huge city of Winnipeg. Of course, we really didn’t know what to expect or the whereabouts of where our school was going to be situated. We got the news around the last long weekend in May 1958, after all the Fort Alexander students went home for a short long-weekend holiday. The remaining students from the northern communities usually stayed at school.

Father Bilodeau had a meeting with the remaining students, and this was the day that he told us about the new school that we were going to in the fall. He told us that we would take a trip to Winnipeg to go and see our new school.

We were driven to Winnipeg in a truck with no seats; we all had to sit on the floor. There were two little windows on each side of the closed truck, which was driven by one of the Religious Brothers. As we were travelling, I guess it was on Main Street, one of the girls yelled, “Look at that beer bottle!”—it was spinning around in the air. We all turned quickly to look out of the little windows, it looked so funny to us. Then one of the girls said, “I wonder if there is beer in it?” We all started laughing hard and loud. I think we sort of scared our driver. Anyways, that was our funny and exciting ride.

I guess we must have come all the way down Main Street and Portage Avenue to Academy Road, until we arrived where the new residential school was going to be.

Mind you, while we were there, a train came by and sure made a lot of noise and shook the building. We all said, “Oh my, that train is going to keep us awake.” One of the girls said, “Oh well, that will be our wake-up bell, no more Sister’s bell.”

Figure 2. Portage and Main, 13 November 1958.

We pulled into the driveway and followed the driver to the building. I guess the principal came in a different car, but I cannot recall if anybody else came.

We toured around the stale, smelly building, and we were scaring each other at the same time, saying that we might find a dead body as we went to all the rooms.

We were glad that the building was cleaned up before we came back to school in the middle of August 1958.

Our recreation room was on the main floor on the west side of the school. Our washrooms were off the hallway on the main floor. There were washrooms and shower rooms upstairs, but we were never allowed to go upstairs during the day unless there was an emergency.

There were two huge dormitories for us upstairs, one on the west side and one on the south side, and the beds were arranged row by row.

The boys’ side of the residential school was on the east side, overlooking the principal’s office. The staff room was at the front of the building across from the office. From the windows of his office or the staff room, the principal could keep an eye on us all the time.

We, the girls, were never allowed to mingle with the boys, not even in the cafeteria, as there were designated sections for boys and girls. As each had their own side of the room, there was no such luck to sit with boys during our mealtimes. If we got caught with a love note, it was read aloud in the cafeteria during lunch hour, then it was “Wow!”

After, we were given our class schedules, school chores, and most of all our school rules. These were not too strict, as we were allowed to smoke at the designated time. We also had a canteen after classes. We were able to purchase our cigarettes, drinks, and candy bars at this time. I don’t remember chips, except Cracker Jack and boxed popcorn.

Also, our in-school chores were designated for two weeks at a time, then we changed our work. It was nice, and we looked forward to where we would work. My favourite work was serving meals. The boys had to do their own chores on their side of the school.

Figure 3. Dorothy Crate (née James) interviewed outside of Assiniboia’s classrooms building, June 2017.

During the first year and week of August 1958, after we arrived at the new school, we asked the nun supervisor if we could go shopping at the T. Eaton Store. She had to ask the principal first and we were allowed to go as long as we returned by 6:00 p.m.

The T. Eaton Store was the company from which we used to make our mail orders from the catalogues, which were sent to all the northern reservations. We used to look forward to receiving these catalogues. But we had no idea where exactly the T. Eaton Store was and nobody offered to drive us there. We had no idea of how to catch a bus either.

Anyway, three girls started walking all the way down Academy Road and came to a bridge, which was the Maryland Bridge. There we saw a store and went inside to ask directions. The storekeeper wrot...