![]()

The “B-Minor Flute Suite” Deconstructed

New Light on Bach’s Ouverture BWV 1067

Joshua Rifkin

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Ouverture for Flute, Strings, and Continuo (BWV 1067)—in common parlance, “the B-Minor Flute Suite”—has long enjoyed a favored position both within his own instrumental output and in our musical practice at large. Indeed, for generations of performers and listeners, the work has become virtually emblematic of the flute itself. As its continued preeminence reminds us, moreover, the ouverture has evaded the scholarly scythe that has so painfully diminished the body of Bach’s instrumental music with flute—identifying this piece as a transcription from a different medium, disqualifying that one as a product of his authorship altogether. If anything, recent scholarship seems only to have heightened the ouverture’s significance: with most authorities now agreed on placing its creation in the late 1730s, it ranks as the very latest of Bach’s original compositions for larger instrumental ensemble, the capstone to a rich succession of works stretching back at least as far as the Brandenburg Concertos.

The present study will upset—or at least seriously qualify—this gratifying picture. Let me immediately forestall any worry that I shall seek to remove BWV 1067 from the canon of Bach’s works: both the transmission and, surely, the music itself leave no room for doubt that he composed it. But on every other count, we shall see that the evidence tells a very different story from the one familiar to us.

I

The ouverture BWV 1067 survives in only one source from Bach’s lifetime, a set of six parts preserved—together with several more added later by Carl Friedrich Zelter—in ST 154. Table 1 lists the original parts in detail. As it makes clear, Bach himself wrote the flute and viola parts; each of the rest shows the hand of a different, anonymous copyist. Yoshitake Kobayashi’s investigation of the paper and script assigns the set as a whole to “ca. 1738–39”; but Bach’s viola part, although written on the same paper as the others, appears to postdate them by some years—presumably it replaces an earlier copy that had suffered damage or got lost. No. 5, the unfigured continuo, also occupies a secondary position, but of a somewhat different sort: as a direct copy of no. 6, it offers no independent testimony on the origins or readings of the music. For obvious reasons, therefore, the discussion that follows will concern itself essentially with parts nos. 1, 2, 3, and 6.

Table 1. Ouverture BWV 1067: Original parts

| Part | Scribe |

| 1. Traversiere | JSB |

| 2. Violino 1 | Anon. N 2 + JSB (heading, title, clef, time and key signatures + revision) |

| 3. Violino 2 | Singular + JSB (heading, title, clef, time and key signatures + revision) |

| 4. Viola | JSB |

| 5. Continuo (unfigured) | Anon. N 3 + JSB (heading, title, clef, time and key signatures) |

| 6. Continuo (figured) | Singular + JSB (heading, title, clef, time and key signatures + figuring and revision) |

Of these, we must first consider the three nonautograph parts. In each instance, Bach himself appears to have got the copyist started: not only did he write the heading at the top of the page, but he also entered the movement title, clef, key signature, and time signature. We may perhaps take this as more than a simple courtesy. On several occasions where Bach provided the initial elements of a part, he did so to signal a notational change—usually to tell the scribe to copy the music in a key different from that of the parent manuscript. I might cite two examples here. In 1724, Bach amplified the scoring of the Weimar cantata Gleichwie der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt (BWV 18) with a pair of recorders that double Violas 1 and 2 of the original instrumentation at the upper octave. While the violas, tuned to the high Chorton pitch standard inherited from the original version, play in G minor, the recorders play in A. The wind parts thus involved transposition to both a new register and a new key, not to mention a new clef; Bach eased his copyist’s task by writing out the opening bars of each part as a guide. In the 1740s, Bach prepared a version of the cantata Liebster Gott, wenn werd ich sterben (BWV 8) that transposed the work from E major to D. Although he wrote most of the instrumental parts himself, the three that he did not all show autograph title, clef, and signatures.

I do not mean to imply that the entry of initial clefs by Bach inevitably denotes transposition; indeed, the unfigured continuo part of

BWV 1067 offers a useful reminder on this very point. Nevertheless, in light of the other examples just considered, we

may well suspect that Bach and his assistants took the music of

BWV 1067 from a source notated in a key other than B minor. It does not, in fact, take much effort both to confirm this suspicion and to establish the key in question. As we see from

Table 2, the violin and continuo parts show a number of corrections and other features suggestive of transposition up a tone. The autograph flute part, although it does not contain any clearly altered notes, reveals an unusually high percentage of accidentals placed squarely a degree too low, as well as a single appoggiatura written as f

" instead of g" and two more on a" that lack their leger lines. As the viola part could in principle

derive from its lost predecessor in the set—and hence from a model in B minor—we might not so readily think to investigate it for hints of transposition. Yet not only does it contain its own share of misplaced accidentals, but the composer unmistakably thickened the first note in m. 9 of the Sarabande upward from a low start, and he just as unmistakably wrote the third note of m. 8 in the Battinerie as e' rather than the f

' that the harmony demands.

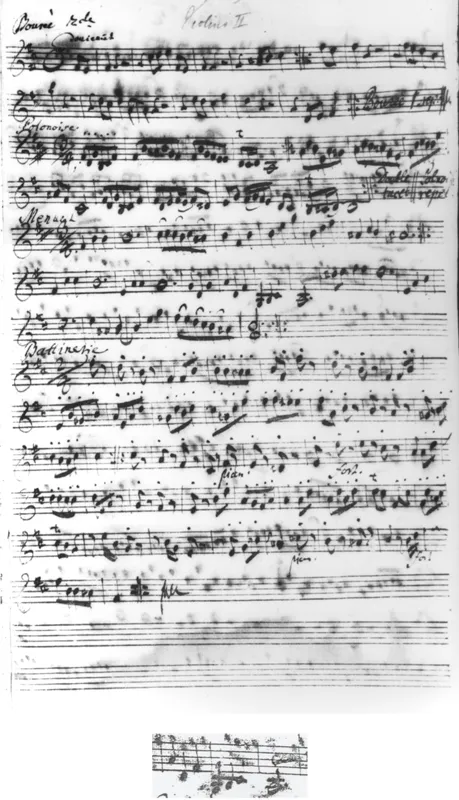

A final, if more circuitous, pointer arises from a detail in the second-violin part. At m. 15 of the Menuet, the first note as entered by the copyist read g'; as Plate 1 makes clear, someone other than the copyist, no doubt Bach himself, carefully excised it and replaced it with the same note an octave lower. With the original reading restored, the string and continuo parts descend to exactly one tone above the lowest limit of the violin, viola, and cello: A, D, and D, respectively. By all indications, therefore, Bach and his copyists drew the parts to the ouverture from a source—more likely than not a score—that presented the music in A minor.

What can we establish about the A-minor version of the ouverture other than its key? As Bach entrusted the string and continuo parts of the transposed version to copyists, we can assume that they simply followed their model verbatim; in this respect, therefore, the ouverture as we know it—barring any revisions made after copying—would not have differed at all from its predecessor. But the solo part, clearly, did not go unchanged, otherwise Bach would hardly have gone to the trouble of writing it out himself. This fact obviously raises the question of the original solo instrument. We can safely eliminate the flute. Even if we could imagine the solo line written in a way that would avoid the present occurrences of d'—the lowest note on the Baroque flute—in both solo and tutti passages, the overall tessitura would still put the music uncomfortably low for the instrument; and in any event, it seems hardly credible that Bach would have written a concerted work with so little regard for the properties of its featured instrument that he ultimately felt obliged to transpose it to a more favorable key.

Table 2. Indications of transposition in the violin and continuo parts of BWV 1067

Movement,

Measure

Ouverture | Part | Remark |

| 8 | Violin 2 | Last note originally a step lower |

| 15 | Violin 2 | 5th note originally a step lower |

| 47 | Violin 2 | 3rd note begun a step lower |

| 51 | Continuo | 4th note originally a step lower |

| 81 | Violin 2 | 4th note originally a step lower |

| 97 | Violin 1 | Last note begun too low |

| 109 | Violin 2 | 2nd note probably begun a step lower |

| 146 | Violin 2 | 2nd note begun a step lower |

| 158 | Violin 2 | Whole note placed considerably too low |

| 208 | Violin 2 | 2nd note possibly begun a step lower |

| Rondeaux |

| 11 | Violin 2 | Last note originally a step lower |

| 18 | Continuo | 1st note originally a step lower (?) |

| 40 | Violin 1 | Second half of measure stemmed as if a step lower (cf. m. 42, as well as Ouverture, m. 88) |

| Sarabande |

| 23 | Violin 2 | 3rd note originally a step lower |

| 27 | Continuo | 1st note originally a step lower |

| 30 | Violin 2 | Last note originally a step lower |

| Bourèe 1 |

| 19 | Violin 2 | 2nd note originally a step lower |

| Menuet |

| 1 | Violin 1 | 4th note originally a step lower |

| 24 | Violin 2 | Lower note of double-stop (cf. n. 16) originally a step lower |

| Battinerie |

| 2 | Violin 1 | Notes 2–3 stemmed as if a step lower |

| 12 | Continuo | 2nd note placed considerably too low |

| 39 | Continuo | Last note placed considerably too low |

Plate 1. ST 154, Viol...