![]()

PART 1

Prelude to War

![]()

1

Recollections of the John Brown Raid

Alexander R. Boteler, Colonel, C.S.A.

STORER COLLEGE, at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia, a flourishing institution “for the education of colored youth of both sexes,” owes its existence to the philanthropic gentleman of New England whose name it has taken. At its fourteenth annual commencement on May 30, 1881, Frederick Douglass, who is undoubtedly the most gifted orator of his race, delivered a eulogistic address on old John Brown, in which he claimed for him “the honor” of having originated the war between the Northern and Southern sections of our Union, summing up his conclusions on this point in the following expressive language: “If,” said he, “John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did, at least, begin the war that ended slavery. If we look over the dates, places, and men for which this honor is claimed, we shall find that not Carolina, but Virginia—not Fort Sumter, but Harper's Ferry and the arsenal—not Major [Robert] Anderson, but John Brown began the war that ended American slavery, and made this a free republic. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy, and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes, and compromises. When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared—the time for compromises was gone—the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union, and the clash of arms was at hand.”

These words, uttered with an emphasis belonging to a strong conviction of their truth, will be accepted by the public as an authentic but somewhat tardy confession of one who, as a confidential coadjutor of Brown in his conspiracy against the South, is understood to have been fully acquainted with his plans and purposes; and the avowal thus frankly made by him is sufficiently confirmed by the contemporaneous facts to which it refers. For, when a complete and impartial history of our late civil war shall be written, it will be seen that the “John Brown Raid,” at Harper's Ferry, in the latter part of 1859, was indeed the beginning of actual hostilities in the Southern States; that then and there the first shot was fired and the first blood was shed—the blood of an unoffending free Negro, foully murdered while in the faithful discharge of his duty! It will be further seen that there and then occurred the first forcible seizure of public property; the first attempt to “hold, occupy, and possess” a military post of the government; the first outrage perpetrated on the old flag; the first armed resistance to national troops; the first organized effort to establish a provisional government at the South, in opposition to that of the United States; the first overt movements to subvert the authority of the constitution and to destroy the integrity of the Union.

Looked at in the light of subsequent events these facts, with their antecedent and attendant circumstances, are so significant that few now can fail to see and none need hesitate to say that “the abolition affair at Harper's Ferry,” in the fall of 1859, was an appropriate prelude to that gigantic war which was so soon to follow it, and which, conducted on a scale commensurate with the magnitude of the work to be accomplished, effectually completed what old John Brown so fatally began—a work concerning which friends of Brown now boast that “Lincoln with his proclamations, Grant and Sherman with their armies, and Sumner with his constitutional amendments, did little more than follow in the path which Brown had pointed out.” (F. B. Sanborn, in “Atlantic Monthly,” April, 1875.) But whatever difference of opinion yet exists as to who fired the first hostile gun in the South—John Brown or General [Pierre G. T.] Beauregard—one thing is certain: If it had not been for a comparatively small class of factious and implacable politicians in both sections—the active abolitionists of the North and the secessionists per se of the South—there would have been no fratricidal civil war, especially if it had depended on the aforesaid extremists to go to the front and do the fighting. But it is enough for us to know what was actually done during a maddened and misguided epoch and what our obvious duty is in these improving times of reestablished peace, and, it is to be hoped, restored fraternity.

Passing by the question, then, as to whether the Harper's Ferry outbreak was “a legitimate consequence of the teachings of the Republican Party,” as was claimed at the time of its occurrence by some of the prominent leaders of that party; disregarding also the kindred inquiry as to whether the forcible extinction of slavery in the South was the logical consummation of a foregone conclusion in the North, where it had long been labored for by a constantly increasing faction who, professing to be governed in their political action by a “higher law” than the Constitution, were willing to “let the Union slide” for the sake of abolition, and who, likewise, on that account, opposing all compromises, persistently urged war at a time when many patriots, North and South, were nobly striving to avert that calamity—I will confine myself here to outlining some of the scenes and incidents that occurred, partly under my personal observation, at the time of Brown's hostile incursion, for which he and his deluded followers paid the forfeit of their lives, and from which the people of the unfortunate town selected for his midnight raid may date the beginning of the end of their former prosperity.

On the morning of the raid, Monday, October 17, 1859, I was at my home near Shepherdstown (ten miles west of Harper's Ferry), and had hardly finished breakfast when a carriage came to the door with one of my daughters, who told me that a messenger had arrived at Shepherdstown, a few minutes before, with the startling intelligence of a Negro insurrection at Harper's Ferry!

She could give no particulars, except that a number of armed abolitionists from the North—supposed to be some hundreds—had stolen into “the Ferry” during the previous night, and, having taken possession of the national armories and arsenal, were issuing guns to the Negroes and shooting down unarmed citizens in the streets. Ordering my horse, I started at once for Harper's Ferry, by way of Shepherdstown, where I found the people very much excited. Their first feeling, on hearing the news, had naturally been one of amazed and, with some, of amused incredulity, which, however, soon gave place to an intense and pardonable indignation.

The only military organization of the precinct—a rifle company, called The Hamtramck Guards—had been ordered out, and as I rode through town the command was nearly ready to take up its line of march for the Ferry, while a goodly number of volunteers, with every sort of firearm, from old Tower muskets which had done service in colonial days to modern bird guns, were joining them. I observed, in passing the farms along my route, that the Negroes were at work as usual. When near Bolivar—a suburb of Harper's Ferry—I saw a little old “darky” coming across a field toward me as fast as a pair of bandy legs, aided by a crooked stick, could carry him. From the frequent glances he cast over his shoulder and his urgent pace, it was evident that the old fellow was fleeing from some apprehended danger, and was fearfully demoralized.

I hailed him with the inquiry: “Well, Uncle, which way?”

“Sarvint, marster! I'se only gwine a piece in de country for ter git away from de Ferry.”

“You seem to be in a hurry,” said I.

“Yes, sah, I is dat an’ it's ’bout time ter be in a hurry when dey gits ter shootin’ sho ’nuff bullets at yer.”

“Why, has any one been shooting at you?”

“No, not exactly at me, bless de Lord! kase I didn't give ’em a chance ter. But dey's been a-shootin’ at pleanty folks down dar in de Ferry, an’ a-killen of ’em, too.”

“Who's doing the killing?”

“De Lord above knows, marster! But I hearn tell dis mornin’ dat some of de white folks allowed dey was abolitioners, come down for ter raise a ruction ’mong de colored people.”

And on inquiring if any of the colored people had joined them, “No-sahree!” was his prompt and emphatic answer, at the same time striking the ground with his stick, as if to give additional force to the denial.

I insert this colloquy simply because it tends to illustrate the fears and feelings of the Negroes at Harper's Ferry as well as in the surrounding region, at the time of Browns's abortive attempt to secure their aid. Somewhat relieved by the assurance that the Negroes had nothing to do with the trouble, I continued on my way to Harper's Ferry, arriving a little before noon.

It is necessary here to give a summary of the day's doings up to the time of my arrival at the Ferry, together with a preliminary explanation of Brown's plans and preparations. From facts which are fully admitted by his friends, it is now known that for more than five and twenty years Brown had cherished the idea of making slavery “insecure” in the States where it existed by a pre-concerted series of hostile raids and servile insurrections, and that at least two years previous to his raid on Harper's Ferry he had selected it as a suitable place for the initial attack. His three principal reasons for choosing the Ferry as his point d'appui were: (1) The presence of a large slave population in what is known as “the Lower Valley,” which is that fair and fertile portion of the great valley of Virginia embraced within the angle formed by the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers before their confluence at Harper's Ferry; (2) the proximity of the Blue Ridge range of mountains, where, in their rocky recesses and along their densely wooded slopes, he would be comparatively safe from pursuit and better able to protect himself from attack; (3) because of the location at Harper's Ferry of the United States armories and arsenal, in which were always stored many thousand stands of arms without sufficient guard to protect them.

His plan was to make the Blue Ridge Mountains his base of operations, and descending from them at night with his armed marauders, to attack the unprotected villages and isolated farm-houses within his reach, wherever and whenever his incursions would probably be least expected.

These raids were to be made on the Piedmont side of the Blue Ridge, as well as in the Valley—his forces acting as infantry or cavalry, according to circumstances, and to have no scruples against taking the horses of the slave-holders and other needed property.

As many of the slaves as could be induced to abandon their homes were to be armed and drilled, and, by recruiting his “army of occupation” in this way, he expected soon to raise a large body of blacks, reinforced by such white men as he could enlist, with which he believed he could maintain himself successfully in the mountains, and, by a predatory war, so harass and paralyze the people along the Blue Ridge, through Virginia and Tennessee into Alabama, that the whole South would become alarmed and slavery be made so insecure that the slaveholders themselves, for their own safety and that of their families, would be compelled to emancipate their Negroes. It was, also, part of his plan to seize the prominent slave owners and hold them prisoners either “for the purposes of retaliation,” or as hostages for the safety of himself and his band, to be ransomed only upon the surrender of a specified number of their slaves, who were to be given their freedom in exchange for that of their masters.

When Brown went to Europe in 1848, to sell Ohio wool, it is said that he inspected fortifications on the Continent, “with a view of applying the knowledge thus gained, with modifications of his own, to mountain warfare in the United States”; and though not much given to books, he read all he could get that treated of insurrectionary warfare. Plutarch's account of the stand made for years by Sertorious, the Spanish chieftain, against the combined power of the Romans, it is said, was frequently referred to by him in conversation with his friends, as also the war against the Russians by Schamyl, the Circassian chief; that against the United States by Osceola, in the Everglades of Florida; and that so successfully fought by Toussaint L'Ouverture and Dessalines, in St. Domingo. He likewise regarded his own bloody experiences in Kansas as so many practical lessons on the skirmish line; and he also believed himself to be an appointed agent of Deity in the work he intended to do.

He allowed few of his friends besides his immediate followers to know his plans; but there were certain pseudo-philanthropists in the North who knew all about them, and who now boast that, with a full knowledge of his intentions, they “were indifferent to the reproach of having aided him” with means for their execution. While the self-sacrificing bravery of Brown has a claim to our respect and admiration, however much we may condemn his unlawful and treacherous attack, Southern people can feel only abhorrence and contempt for the cowardly conspirators who encouraged his design without having the manliness to share its dangers.

John Brown's first appearance south of Mason and Dixon's line was on June 30, 1859, at Hagerstown, in Maryland. Coming from Chambersburg, in company with a man named [Jeremiah G.] Anderson, who was one of his “lieutenants,” they remained overnight there, “passing themselves off for Yankees, going through the mountains in search of minerals.” On July 3, he appeared at Harper's Ferry, under the assumed name of Smith, with his two sons—Watson and Oliver—and “Lieutenant” Anderson, passing that night at a small tavern in Sandy Hook, a hamlet on the left, or Maryland, bank of the Potomac, about a mile below the Ferry. The next day, July 4, a farmer, whom I knew very well, met them on a mountain road above the Ferry, when, in reply to his remark: “Well, gentlemen, I suppose you are out hunting minerals?” Brown said, “No, we are not; we are looking for land.” He said they were “farmers from the western part of New York,” whose crops had been so “cut off” by the frosts, that they had concluded to settle farther south.

Subsequent conversations directed Brown's attention to a small tract further up the road, about five miles from the Ferry, belonging to the heirs of Dr. Booth Kennedy, and a few weeks later he rented a portion of it, including “the improvements,” which consisted of a plain two-storied log-house with a high basement, and a small outhouse or shop which was also of logs; for which, with the right to firewood and pasture for a horse and cow, he paid, in advance, thirty-five dollars, taking the property until the first of March following. The place was admirably adapted to the purposes of concealment, being somewhat remote from other settlements, surrounded by dense forests, with its house some distance back from the rarely traveled public road in front of them, and almost entirely hidden from view by undergrowth.

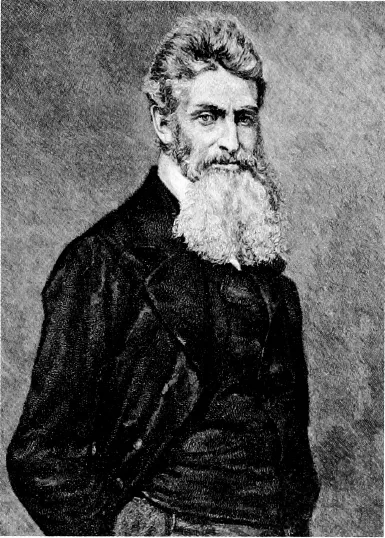

John Brown (Century)

Having thus secured a suitable hiding-place, his men began to gather there—coming from the North, one or two at a time, at intervals, and generally in the night. Meanwhile, there also arrived quietly from the same quarter—great precautions being used to conceal their destination as well as their contents—a number of boxes filled with guns, pistols, pikes, powder, and percussion caps, together with fixed ammunition, swords, bayonets, blankets, canvas for tents, tools of all kinds, maps and stationary; so that few camps were ever more fully supplied for an active campaign than was Old John Brown's mountain aerie.

Sunday night, October 16, was fixed for the foray; and at eight o'clock that evening, Brown said to his companions: “Come, men, get on your arms; we will proceed to the Ferry.” They took with them a one-horse wagon, in which were placed a parcel of pikes, torches, and some tools, including a crowbar and sledge hammer, and in which also Brown himself rode as far as the Ferry.

Brown's actual force, all told, consisted of only twenty-two men including himself, three of whom never crossed the Potomac. Five of those who did cross were Negroes, of whom three were fugitive slaves. Ten of them were killed in Virginia; seven were hanged there, and five are said to have escaped, viz., two of those who crossed the river, and the three who did not cross. Six of the white men were members of Brown's family, or connected with it by marriage, and five of these paid the forfeit of their lives to the Virginians. Owen Brown is the only one of the whole party who now survives.

The following is a list of the party with their respective titles, according to commissions given them under authority of the provisional government, which Brown intended to establish in the South, the constitution for which had been adopted by “a quiet convention,” held in Canada for the purpose, over which Brown presided: John Brown, commander-in-chief; John Henry Kagi, adjutant, second in command, and secretary of war; Aaron C. Stevens, captain; Watson Brown captain; Oliver Brown, captain; John E. Cook, captain; Charles Plummer Tidd, captain; William H. Leeman, lieutenant; Albert Hazlett, lieutenant; Owen Brown, lieutenant; Jeremiah G. Anderson, lieutenant; Edwin Coppic, lieutenant; William Thompson, lieutenant; Dauphin Thompson, lieutenant; Shields Green; Dangerfield Newby; John A. Copeland; Osborn P. Anderson; Lewis Leary; Stewart Taylor; Barclay Coppic, and Francis Jackson Merriam. The three last named were left at the Kennedy farm as a guard, and did not cross the river; the five names italicized were colored men, and the only persons among the actual invaders who did not hold commissions—all compliments of that kind having been monopolized by the white men of the party, as a practical commentary on their professions of fraternity and equality. The army so fully officered beforehand, was not yet raised. According to certain general orders, issued by Brown, October 10, a week before his raid, his forces were to be divided into battalions of four companies, which would contain, when full, seventy-two men including officers in each company, or two hundred and eighty-eight in the battalion. Each company was divided into bands of seven men under a corporal, and every two bands made a section under a sergeant.

When Brown's party arrived opposite the Ferry at the entrance to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad bridge over the Potomac—alongside of which there was, as now, a wagon road—two of the number (Cook and Tidd) were detailed to tear down the telegraph wires, while two more (Kagi and Stevens), crossing the bridge in advance of the others, captured the night watchman, whose name was [William] Williams, and who was entirely too old to make any effective resistance. Leaving Watson Brown and Stewart Taylor as a guard at the Virginia end of the bridge, and taking old Williams, the watchman, with them, the rest of the company proceeded with Brown and his one-horse wagon to the gate of the United States armory, which was not more than sixty yards distant from the bridge. Finding it locked, they peremptorily ordered the armory watchman, Daniel Whelan, who was on the inner side of the gate, to open it, which he as peremptorily refused to do. In his testimony before the U.S. Senate committee, of which Mr. [James M.] Mason of Virginia was chairman, Whelan described this scene so graphically that I here quote a part of it, as follows:

“Open the gate!” said they. I said, “I could not if I was stu...