![]()

CHAPTER 1

Prevailing Approaches to the Study of Neighborhoods and Change

Something that we know when no one asks us, but no longer when we are supposed to give an account of it, is something that we need to remind ourselves of. (Wittgenstein 1958, 89)

Theories of neighborhood change have been constructed since the 1920s (Keating and Smith 1996) to help make sense of the physical, social, and institutional factors altering the status quo of American neighborhoods and affecting larger urban systems. These theories aim to identify factors that cause neighborhoods to change. For example, architectural features and location can increase or decrease demand for a neighborhood, while institutional factors such as zoning, building code enforcement, rent control, lending practices, and discrimination can positively or negatively influence housing market operations. It is also common for researchers to look at changing demographics, including racial or ethnic composition, as well as change in the income level, familial status, and age of household members.

Policy makers and practitioners have long turned to these theories to guide the development of programs and strategies to either offset the negative results of change (e.g., loss in property values, decreasing quality of life) or to encourage change so as to produce positive results (e.g., increased property values, improved quality of life). And although we cannot always make direct linkages between theory and policy (e.g., see Metzger 2000), social science hegemony at particular points in time has framed both how neighborhood change is problematized and subsequent policy solutions.

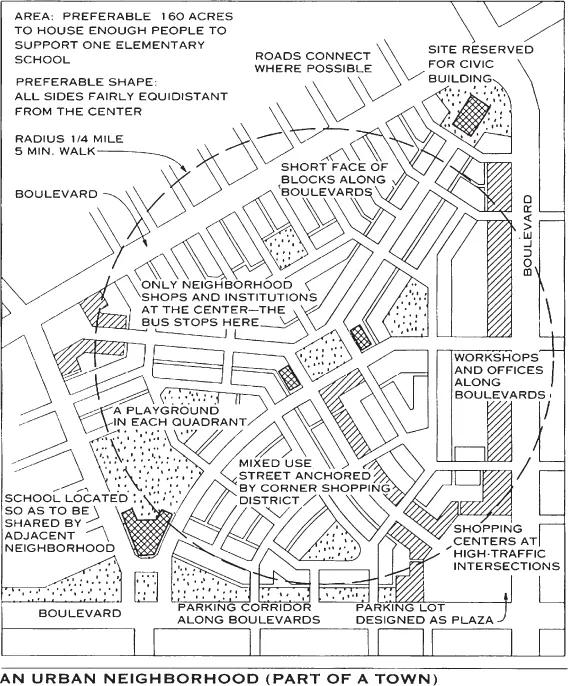

Assuming that the process of developing theory is political (Foucault 1995, 1998; Flyvbjerg 1998), we focus on how theories of neighborhood change have produced a particular discursive space in which to interpret urban dynamics, a space with rules that determine what constitutes “legitimate” modes of distinguishing stable or healthy neighborhoods from unstable and unhealthy ones. Instead of viewing theory as a generalizable conceptualization of space, timeless and disconnected from context, we see it as a product of researchers that generates a particular type of space—in this case the stable neighborhood—for investigation. An early example of this is the neighborhood unit devised by Clarence Perry in 1929. In his famous diagram (Figure 1), the neighborhood is shown as a collection of lots with single-family homes arranged around a school and community center and parks, with curvilinear streets that limit access from outside the neighborhood. Shopping and services are located along busier roads on the periphery but within walking distance of most homes. The scale is generally based on the population needed to fill an American grade school. Accompanying the diagram is a list of principles that guide the location of these different elements.

Figure 1. Neighborhood Unit

Source: Clarence Perry, A Plan for New York and Its Environs. New York: 1929.

Perry’s neighborhood unit is both a real and imagined space. It is conceived, as in being “thought of” or “brought into existence” through action, which in this case was through guidance for developing neighborhoods in a plan for the New York City region. It is also conceptual because Perry is projecting a particular view of what a neighborhood could or should be relative to cultural expectations at the time. Keeping this in mind, our review of neighborhood change theories considers how they not only help describe and explain but also produce urban dynamics.

Framing theory as space producing focuses attention on the relationship between these indicators and the place itself, which when conflated can lead to specific expectations for the site and its occupants that are only partially representative of the experiences of people actually living in the spaces studied. Theory viewed in this way is active; it is neither timeless nor disconnected from the context in which it was developed, and it draws attention to the role of researchers in the process of producing theory when examining urban space. To illustrate this we trace the trajectory of ideas that evolved from early writings of human ecologists, situating each subsequent or new theory in the context in which it was introduced. A common thread we find is an image of stability that is based on neighborhoods being relatively homogeneous and occupied by a majority white, middle- or higher-income homeowners, which continues to underpin contemporary thinking about how to measure and interpret stability.

Most research on neighborhood change has been through either a human ecology or political economy lens. Human ecologists generally view neighborhoods as “natural” units, interconnected cells in the body of the city. Change was assumed to be a recurring process triggered by specific conditions essential to the growth and expansion of the city. In contrast, political economy has treated neighborhoods as historically produced spaces in the city that are contingent upon the controlling forces of power and capital. Clearly both frameworks derive from different epistemologies. Yet both have in common two fundamental features: neighborhood change always follows the same rules, and the space of the neighborhood is assumed to be relatively homogeneous in content. We explore these features next in mainstream (human ecology and its offshoots) and critical (political economy and its relatives) explanations of neighborhoods change.

Mainstream Theories of Neighborhood Change

The origin of mainstream theoretical investigations of neighborhood change in the United States is found in the work of human ecologists at the University of Chicago in the 1920s (J. Smith 1998; Temkin and Rohe 1996). Since then, academic research has posed new theories and models to describe neighborhood dynamics. What follows is a chronological review of the early work of the Chicago School and subsequent theories it generated—filtering, life cycle, racial tipping, and revitalization—and the corresponding assumptions each makes about the cause of neighborhood change.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND INVASION-SUCCESSION

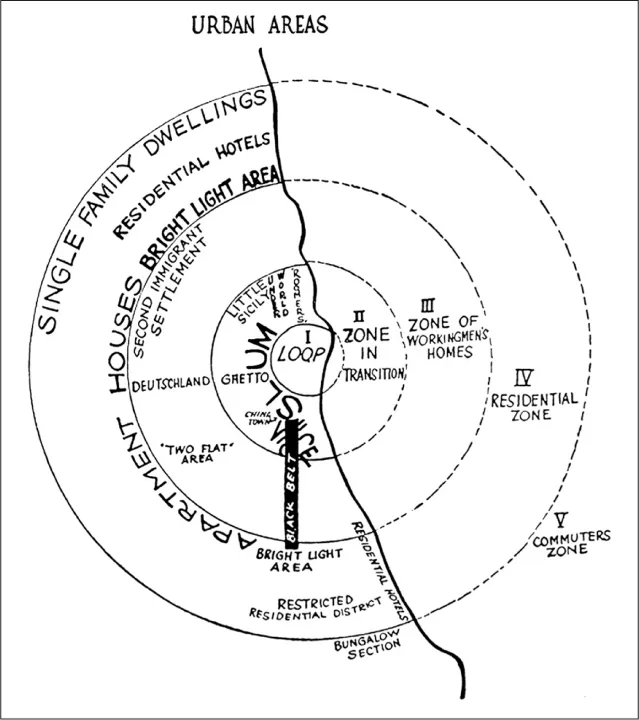

In the early part of the twentieth century, sociologists at the University of Chicago (UC) set out to explain the modern city as a product of human nature. Their premise was that the urban spatial patterns observed in American cities must somehow be essential for the progress of society. In The City (1925), Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, and Roderick McKenzie presented the city as a specific and orderly spatial pattern produced by economic competition and the division of labor in the industrial city. Burgess developed a schematic in which the city appeared as a set of concentric zones radiating from the central business district (Figure 2). Each surrounding zone was identified by dominant household and housing characteristics, with higher-income groups living in lower-density housing furthest from the center. Over time, the city was expected to grow, expanding out from the center. As industry in the center competed for space with surrounding residential areas, inhabitants of the inner zone would then push into the next outer ring (invasion), eventually taking over the physical space of that zone (succession).

In this framework, neighborhoods were assumed to be natural areas where people of similar social, ethnic, or demographic background naturally lived together. They were not alone in their thinking. Tilly (1984) suggests that a paradigm of differentiation evolved in social theory at the time to consider how community was maintained despite the growing diversity of urban space. In this paradigm, segregation in urban space could be explained. Not only were city dwellers expected to live away from work, they were also expected to naturally coalesce in enclaves with people of similar income and heritage to recreate a sense of community that was lost in modern city life. For the most part, these enclaves provided a separate space outside the workplace for social interaction and the production of culture (Katznelson 1981; Harvey 1989).

Figure 2. Concentric Zone Model

Source: Ernest Burgess, “The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project.” In The City, edited by Robert Park, Ernest Burgess, and Roderick McKenzie. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925.

The Chicago School’s early research had a profound effect on the study of neighborhood change, with Chicago becoming the dominant site for investigating social life in industrial urban America. Immigration was of particular interest for these researchers. They assumed that the greater the difference between new immigrants invading a neighborhood and its incumbent residents, the greater the likelihood that succession would occur, often preceded by resistance or even violence. While some UC researchers used ethnographic techniques to produce in-depth neighborhood studies to learn more about the culture of particular groups (see for example Thomas and Znaniecki’s The Polish Peasant in Europe and America [1918] or Zorbaugh’s The Gold Coast and the Slum [1929]), others developed methods that could systematically track population patterns and movement (see Burgess and Bogue 1967), laying a firm foundation for qualitative and quantitative research. UC researchers also instituted the mapping of neighborhoods or community areas along with its demographic studies. The first to employ census tracts as proxies for neighborhoods, they initiated the use of aggregate data and many of the socioeconomic indicators used today to document changes in spatial patterns, including race/ethnicity.

Developed at a time when cities were rapidly growing, human ecology theories provided a logical explanation for urban growth patterns in an industrialized economy. Given the waves of immigrants to American cities, neighborhoods were changing with the rapid infusion of people competing for space. Human ecologists’ underlying assumptions about urban spatial patterns and human nature, however, limited the explanatory value of the ecological model. Assuming that the order of the city in the 1920s, segregated by race, ethnicity, and class, was necessary for social reproduction and economic progress, these theorists excluded from the explanation some factors shaping the space of the city. These factors included the active recruitment of labor to build its industrial base (e.g., Lemann 1992); the social and legal conditions that often kept residents segregated by race, ethnicity, and class (e.g., Massey and Denton 1993); and the deliberate actions of institutions opposed to integration (e.g., Abrams 1955; Aldrich 1975). The exclusion of these processes sets up a narrow interpretation of neighborhood change that privileges a view of the city that is compelled to be differentiated along social factors, particularly race, class, and ethnicity, if it is to grow and develop.

Generally, there is little accounting for exogenous factors contributing to neighborhood change in early ecological models beyond the assumption that growth varies with and is dependent on the larger economic climate. Burgess’s concentric zones assume a city’s growth is determined by an increasing level of commercial and industrial activity in the central business district (CBD), which then pushes out the center, causing change to occur in surrounding zones. Seemingly simplistic in thinking, the Chicago School’s view of urban dynamics reproduced the dominant mind-set at the time, which assumed the CBD determined the spatial patterns of the city (e.g., see Weber 1899). While later work questioned Burgess’s concentric zone model (see Hoyt 1939; Harris and Ullman 1945), it still reinforced the premise that the spatial form of the city was a natural outcome of economic activity. This was also the case with filtering.

FILTERING

Filtering refers to the process where older housing units become available to lower-income families as higher-income families move to newer units on the urban periphery. In early filtering models, the metropolitan area was presented as a single housing market, with a fixed hierarchy of housing units available to different income groups competing for the best housing value (Baer and Williamson 1988). In spatial terms, this conceptualization of the urban housing market complements the concentric zone model described above, locating newer and more expensive homes at lower densities further out from the center to meet the demands of an expanding metropolis. In contrast, though, filtering looked beyond the CBD as the sole driving economic force shaping the city and considered the effects of suburbanization.

Originally introduced in the mid-nineteenth century, filtering was first used in the 1930s by Homer Hoyt to connect physical and economic obsolescence of housing units with neighborhood change. A University of Chicago economist, Hoyt employed filtering to explain American urban spatial patterns he observed in empirical research completed for the US Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Based on a study of 142 cities, he concluded that increasing income levels encouraged residents to seek better housing being built at the periphery of urbanized space. Movement out by these residents freed up the aging housing stock, which then provided new homes for lower-income groups. Rather than invasion, these families were simply filling up homes made available to them. Considering the welfare effects of filtering, this distinction allowed filtering to appear ambiguous, a process that can produce both negative change and positive outcomes.

As a theory to explain the relationship between the aging housing stock and neighborhood change, filtering helped make sense of physical deterioration in central cities as part of a larger urban dynamic that pushed and pulled middle-class urban dwellers out to improve their living conditions. In the late 1930s, and even more so following World War II, households were leaving behind the dinge and congestion in the city and seeking out new housing opportunities in the suburbs. Filtering, however, generally assumes that this is occurring in a free market economy without barriers such as discrimination (see Squires 1994) or a spatial mismatch of supply and demand that prevents housing markets from operating “perfectly” (Baer and Williamson 1988). And, as with human ecologists, filtering theories assumed th...