![]()

1

Programmed Chaos: Dewey Phillips on the Air

Oh, yessuh, good people, this is ol’ Daddy-O-Dewey comin’ atcha for the next three hours with the hottest cotton-picking records in town—(aside: Ain’t that right, Diz? “That’s right, pahd’ner.”). Yessir, we got the hottest show in the whole country—Red, Hot and Blue coming atcha from W H Bar B Q right here in Memphis, Tennessee, located in the Chisca Hotel, right on the magazine floor—I mean mezzanine floor (aside to himself: Aw’ Phillips, there you go again, you’re always messin’ up!).

On the air, the real Dewey Phillips was always a bit stranger than any fictional radio character ever invented. The style was without precedent. He made no effort to imitate anyone on the airwaves or in the entertainment business. Most fans agree that they had never heard anything quite like him and no doubt ever will again. In essence, he did nothing less than deconstruct Memphis radio entertainment during the 1950s, and in the process he proclaimed a kind of Declaration of Radio Independence for all future programming. Like Elvis, his style not only violated a staid and conventional past but also marked a quantum leap into an irreversible future.

Above all, there was no one around for comparison. One writer, noting that Dewey was a one-of-a-kinder, quickly added, “One was enough.” Elvis’s famous response to Marion Keisker’s question, “Who do you sound like?” (“Why, I don’t sound like nobody, m’am”) could also apply perfectly to Elvis’s close friend and unofficial mentor, Dewey. Dewey didn’t sound like anybody but Dewey.

On his show, he was a combination of a kid in a candy store and a bull in a china shop. A master of unpredictability, his anything-goes-and-tohell-with-the-rules-and-the-regular-format-approach-cause-I’ll-do-any- damned-thing-I-want-to attitude on the air made his nightly Red, Hot and Blue program synonymous with radio entertainment in Memphis and the Mid-South during the 1950s. His WHBQ studio was the broadcasting epicenter of the rock ’n’ roll revolution.

“He was completely without a governor,” exclaims Charles Raiteri, a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi, Dewey Phillips expert, and a longtime observer of the Memphis music scene. “There was no way you could control him. When he was in that broadcasting booth he was going to do and say what he wanted to and that was it.” Sun Records legend and Dewey’s consummate lifelong friend Sam Phillips, who with every utterance on the topic normally exuded respect and admiration for Dewey, was no apologist for his behavior on the air, beginning with his celebrated manner of operating the control board: “Dewey was not too mechanical,” he recalled. “When Dewey Phillips was in a little control room, I mean things were flying off the wall. I mean it was a three-ring or a four-ring circus.” Pointing out that it was absolutely necessary for WHBQ to always have someone else in the studio with Dewey to make sure things were reasonably under control, Sam said diplomatically, “Dewey was not into production. Dewey had a little problem with his mouth [laughter]. Whatever came in his mind, he would say it.”1

His performance between records could best be described as one endless stream-of-consciousness monologue. So rapid-fire was his machinegun delivery that there was never time for him to think out what he was going to say, let alone carefully plan a structured program. Above all, there was never a hint of order or sanity. The foot-to-the-floorboard personality and the revved-up rhetoric spewed forth in a constant fusillade of senseless non sequiturs. Most of the time, listeners felt they were being bombarded by what one writer termed a “verbal assault.”2

The immediate audience reaction was one of unalloyed fascination— albeit not always positive, especially among those accustomed to “normal” radio programming. Robert Johnson, the Memphis Press-Scimitar entertainment writer, was closely acquainted with Dewey and observed that the Memphis listening audience of the 1950s was divided into two groups: Those taken by everything Dewey did, and “those who, when they accidentally tune in, jump as tho stung by a wasp and hurriedly switch to something nice and cultural, like Guy Lombardo.”3

Dewey’s on-the-air escapades are now the stuff that help manufacture legends. In order to savor them completely, however, you must begin by recalling what Memphis radio was like in 1949, when he first began to attack the Mid-South airwaves. Music was monotonously pedestrian (“I’m Looking over a Four-leaf Clover” and “How Much Is That Doggy in the Window?”), and most Memphis stations spent the better part of their broadcast day carrying soap operas and variety shows from the network. Local programming was definitely a bit livelier with country and western bands or an occasional black gospel group, but staff announcer Fred Cook remembers that when he joined WREC in 1950 there was a pipe organ built into the side of the studio, and owner Hoyt Wooten’s secretary played it for live shows.4

Most important, Memphis radio was still characterized by radio announcers who were supposed to sound like, well, like radio announcers. They were, that is, supposed to convey their message in impeccable English, slowly articulate each phrase in perfect cadence, speak in carefully modulated tones, and always enunciate each syllable.

Come again! Dewey Phillips had a hard time making simple sentences let alone trying to enunciate them slowly. Proper grammar? Forget that one, too. Maybe even forget the entire English language. He not only slaughtered it, but there was also no such thing as actually “reading” a commercial. Copywriters knew better. He was usually supplied with a “fact sheet” from which he could ad lib commercial spot announcements. Whenever he attempted the impossible and actually tried to read a commercial all the way through—a practice sponsors strongly discouraged—he usually botched things so badly that he’d say, “Aw, Phillips, you’re always messin’ things up.”

But who cared? His highly stylized, streetwise argot might not have had correct syntax, but when it came to selling a sponsor’s product he left grammarians standing in the dust. “He seldom spoke the King’s English in the grammatical sense,” Sam Phillips said, “but he knew he could communicate.” Indeed, it was Dewey’s remarkable ability to ad lib spot announcements that brought some of his greatest fame. He made Falstaff Beer the favorite of Mid-South listeners not because he read coherent commercials about it but because everyone remembered his ad-lib catch phrases. “If you can’t drink it, freeze it and eat it,” he’d scream. “If you can’t do that, just open up a rib and pour it in.” Not a single sponsor—certainly not Herb Saddler, the owner and distributor of Falstaff—bothered to complain for a single Memphis radio minute.

That Dewey would do the unexpected was always anxiously expected. In fact, the inability to predict what he was going to do was the only thing listeners to Red, Hot and Blue could rightfully predict. That was what made him so fascinating. You didn’t know what you were going to hear when you tuned in, but you knew it wouldn’t be said the same way on any two occasions.5

Despite the unpredictability there was nonetheless a certain method to the madness. You could be pretty certain, for example, that at some point in the evening Dewey would do one of the following: cue up a record right on the air; play two of the same records simultaneously—one slightly ahead of the other—in order to get an echo effect; put his hand on a record and stop it in midplay; or talk continuously the entire time the record was spinning.

Most people who observed Dewey’s programmed chaos on the air say they never saw him actually cue up a record except when he played two at once. Most of the time he’d put a record on the turntable, slap the needle down, start talking, and turn up the volume. You could hear the crackling static as the needle ran around several grooves before it started, and maybe—if you were lucky—he’d quit talking when the first part of the record came in. As often as not, however, he’d talk some more. Sometimes, in instances when he would talk through the entire vocal, or if he wanted to hear a favorite part of the vocal again, he’d just pick up the needle and set it back down.6 His favorite practice was to stop a record he didn’t like by screeching the needle across it while it played. The writer Stanley Booth, who spent a considerable period of time hanging out with Dewey, says, “Every time I start to cue a record and the arm falls off the turntable I tell people I went to the Dewey Phillips school of broadcasting.”7

Bob Lewis’s 75-cents-an-hour job as Dewey’s first gofer required him to do a great many things around the studio, but running the control board was not one of them. After being sufficiently broken in, Dewey was allowed to run his own board. According to Bob, however, “The whole thing was foreign to him. Things like proper [volume] levels just didn’t bother him. Sometimes the level would just ‘peg in the red’ for long periods of time.” (In radio jargon that meant the sound was loudly over-modulated, causing the needle to cross into the forbidden red area.) Lewis laughs when he recalls how he would cringe whenever Dewey wanted to play a record that was badly warped. “The needle would be skipping, so Dewey would get a heavy object, like a book or something— and actually put it on the [turntable] arm to force it down so the record would play.” Lewis admits not being able to “even imagine what the engineers would have done if they could have seen that one.”8

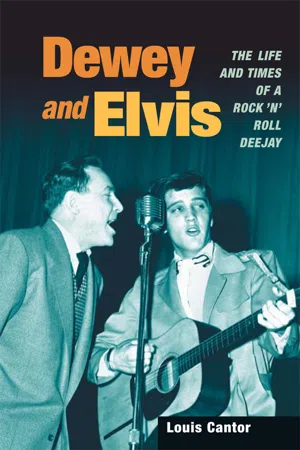

Part of Dewey’s spontaneity encompassed chatting over the air with people who dropped by the studio. Never a traditional interviewer (no such rigid formality for Daddy-O-Dewey), most conversations with guests were carried on without disruption from whatever else he happened to be doing at the time. Sam Phillips recalled that Dewey’s legendary first interview with Elvis was a rare event for Red, Hot and Blue. Except for Elvis, he seldom sat interviewees down in front of the microphone and talked directly to them. Most of the time he would chat with them while records were playing, scream at them from the other side of the studio, or use noisemakers to interrupt what they were saying.

This is rather remarkable considering those who, at one time or another, dropped by a typical Dewey Phillips show. It was common to see big-name people in the control room with him. Over the years, most had come to be close friends who would stop by for a quick visit whenever they were in town.9 The list Dewey’s widow Dorothy (or Dot, as she likes to be called) kept of everyone he interviewed during just one year reads like a who’s who of American entertainment for 1954. Besides Elvis, of course, there was “Roy Hamilton, B.B. King, Joe Hill Lewis, Ivory Joe Hunter, Kay Star, Jimmy Witherspoon, Fats Domino, Hank Williams, Hank Snow, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Faron Young, … Dizzy Dean, Jane Russell, Patti Page, Lionel Hampton, Joe Liggins, Kim Novak, Natalie Wood, Nick Adams, … Carl Perkins, [and] Johnny Cash.”10

It was quite common for Dewey to talk to guests on the air, but the process bore little resemblance to a typical and orthodox radio interview. Whenever a studio guest appeared, Dewey would begin talking, usually with the mike open and ignoring the fact that the guest was all the way across the room. Sometimes Dewey would repeat whatever was said, but more often than not he’d try to pick up the guest’s voice from wherever they happened to be standing by turning his own control board mike up full volume and letting the guest holler.11

While he worked the board, Dewey’s sleight of hand with his microphone’s volume level makes for some of the best on-air stories about him. Stanley Booth remembers one night when the studio was full of the big boys—Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun from Atlantic Records and the flamboyant Leonard Chess from the rival Chess label. Dewey was always at his craziest when they were around, and this night was no exception. These people were pros, Stanley says, and they knew proper procedure during a live show. You keep absolutely quiet when the microphone is open and the on-air sign lights up. At the end of the record, Dewey opened the mike but secretly slipped the volume level down so he could not be heard. Then, Booth recalled, he “pretends as if he were talking on the air. This means that the ‘on-air’ switch is on but the level is down to zero, and Dewey is saying ‘motherfucker this and motherfucker that’ and they’re thinking he’s on the air.”12

Unprogrammed programming was the characteristic trait of a typical Dewey Phillips show. At first, station personnel tried to suggest a little organization, maybe even drawing up a list of the records he might play prior to his show, but that, like all other efforts at superimposing order, quickly fell by the wayside. Just trying to keep track of the records Dewey actually played on a given night was not easy says Louis Harris, who should know. Harris worked with George Klein inside the studio, helping him help Dewey. “I was kind of the ‘gofer’s gofer,’” he says with a chuckle. Sometimes, Harris remembers, Dewey would have a general idea of what he was going to play, and Louis and George would help him pull records before the show. Once the show started, however, the usual pandemonium followed. “He’d have records scattered everywhere, and he’d holler, ‘Gimme that record over there,’” Harris says, but because of the total disarray by that time “I wouldn’t even know which one he was talking about.”13

What seemed like total chaos was actually Dewey’s strongest suit. Given conventional radio at the time, much of the audience’s attraction to him was this very distinct lack of on-air formality. Gut-level spontaneity and the way he would generally botch up everything on the air are the very things that endeared him to the audience. “Dewey was just Dewey,” observes Charles Raiteri. “He’d make a mistake and he’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, Phillips, you’re doing it again. Messin’ up.’” That, Raiteri says, made Dewey much more human, and fans ate it up. “It was like there was a ‘real’ person on the air instead of a ‘radio announcer.’ And that was a big part of his charm.”14

Contemporary columnist Robert Johnson, commenting on Dewey’s unrestrained spontaneity, remarked, “Sometimes I wonder if there is a real Dewey, or if he’s just something that happens as he goes along. He says whatever happens to come into his head, and there have been times when it was the wrong thing.” Johnson noted that a newcomer to the city, hearing Dewey for the first time, might be shocked. But once past that initial impression, which sometimes seemed “crude and low-brow,” Dewey “came over the air as the voice of a rather strange friend, whom they knew and understood.”15

Some of Dewey’s fans, of course, found him irresistibly captivating. His ardent listeners, especially the young, impressionable ones, were so caught up in the craziness that they ignored most everything else they were doing. Memphis musician Jim Dickinson remembers going to dances at White Station High School in Memphis at the time Red, Hot and Blue was on the air: “There’d be as many people in the parking lot listening to Dewey as there were inside at the dance.” One particular night, he recalls, Dewey had just gotten his hands on Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally.” “He played it about ten times in a row, and nobody did things like that except Dewey. So everybody went out in the parking lot at the dance to find out how many times Dewey would end up playing it.”16

More than anything else, Dewey enjoyed himself on the air and loved every minute of being there. He frequently sang over the records he was playing, to either the delight or consternation of listeners, and even made a record on the Fernwood label, both sides of which—“I Beg Your Pardon” and “White Silver Sands”—he played repeatedly without identifying himself as the singer.

He was doing exactly what he wanted to do. So married was he to his job that he wa...