![]()

American Nomadic

Introduction

I have to make one remark. I do not humanize her. I do not make an attempt to humanize her. She is simply a human being. Period.

—Werner Herzog, 2012

To say that Werner Herzog is a major figure of contemporary film is an understatement. While not a name of the household status like his generational peers Spielberg, Lucas, or Scorsese, among even mild cinephiles to say “Herzog” is to invoke a style, an attitude, a mystique, an institution, even something of an industry.

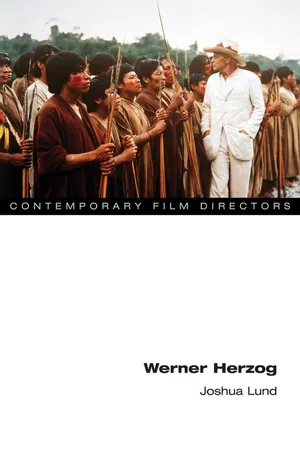

Associated with the New German Cinema in his early career, today Herzog is a transnational celebrity artist, whose themes and narratives spring from landscapes around the globe. Comfortably inhabiting the auteur tradition, even while forever attempting to excuse himself from it, he is most fundamentally a film director. But he is also a screenwriter, producer, and actor. He is the author of a few books (essentially published diaries) and he regularly stages and directs operas for some of the most illustrious companies and most prominent stages in the world. Lately he has become something of an educator, lecturing, leading workshops, convening seminars on the lesser-known aspects of filmmaking (from lock picking to permit forging). His first feature film, the critically successful Signs of Life (1968), premiered when he was twenty-four years old. Herzog’s reputation evolved over time, as critics and the public began to slowly grasp the achievement of his most ambitious early film, Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes (Aguirre, the Wrath of God, 1972). From Aguirre to this day, Herzog has cultivated the reputation of a kind of friendly renegade of the cinema, and his projects are famously marked by some extraordinary detail that links the profilmic to the larger world of production: casting a wayward street musician as the protagonist of two major films, shooting with an entire company placed under the spell of hypnosis (administered by the director himself), pulling a steamship over a small mountain, collaborating with large groups of unprofessional actors, importing two thousand rats to an unexpecting Dutch village, working regularly with Klaus Kinski, and so on. Today he is a good-natured icon, regularly offering unparalleled eloquence on the significance of cinematic images and standing as the object of affectionate parody (see the YouTube shorts “Werner Herzog Reads Madeline” or “Werner Herzog on Vegetarianism”) and even self-parody (see, for example, his cameos in American cartoons Rick and Morty, American Dad, and The Boondocks). His films come in all shapes and sizes, have won numerous international awards, and span more than sixty titles (and rapidly counting), with a good two dozen since 2000. In short, Herzog’s stature as a major filmmaker of our time is well beyond dispute.

But this biographical sketch is not in itself a reason to rethink Herzog today. Everybody wins a prize at some point, quantity is not a virtue, and daring always runs the risk of careening into gimmickry. The reason to consider Herzog today is that his body of work represents a sustained meditation on the modern human condition, one whose challenges resonate ever more clearly in our alarming historical present, a moment in which the world-system is in crisis and the earth, literally, is on fire. The insights that emerge from, and the questions that are asked by, Herzog’s films speak to the centrality of the cinema in both producing and provoking our interpretation of the world. If not alone, Herzog is unusual in the courage with which he has staged the most ominous themes of modernity, distilled those themes to the psychological, even melodramatic, norms of contemporary storytelling, and successfully captured this relation within a context of image and sound that consistently leaves the spectator unsettled. The critical and (infrequent) commercial success in this effort has left him in the position of a cult director whose films are now regularly taught and curated at institutions around the world. In considering his output and stature, few systematic analyses of his work exist. His artistic and critical project has not yet been thoroughly explored.

Four major, overarching themes define the bulk of scholarly work on Herzog to this point: (1) The national question, namely Herzog’s harried relation with German identity and the multiple studies that take up the topic of his associations with the New German Cinema, German expressionism, German romanticism, the US-based film industry and history, and the like. (2) The intertextual elements of his films, how they relate to other films or to their literary and historical source material. (3) Herzog’s cult of personality and its implications for an ethics of filmmaking, such as his relations with actors, crew, possibly vulnerable extras, fragile landscapes, standard industry practices, state policy, and so on. And, (4) perhaps most prominently, his much problematized statements on the relations between aesthetics and truth—what Herzog often characterizes as his commitment to an “ecstatic truth,” truth expressed not by an accounting of facts but by the cinematic possibility of expressing a “deeper” truth through stylization—that often lead to philosophical explorations of the nature of the image (especially landscape) in Herzog’s work and to the director’s controversial use of documentary form.

Any account of Herzog’s career trajectory and its importance (artistic, critical, historical) requires attention to all these themes, and they are certainly all at play in this study. None, however, operates as this book’s analytical center. Instead, this project takes up a peculiar problem for the interpretation of Herzog’s work. In a nutshell, we can call this the political problem. And by this I mean political in the widest sense, as the objectification and contemplation of power relations (as opposed to the identification of ideological affiliations or implications). In turning to the political in Herzog’s work, we are immediately confronted with a puzzle, one placed before us by the director himself. It works like this:

On the one hand, in Herzog’s ample and unusually authoritative discourse on his own films is a commonly rehearsed refusal of the political: he summarily rejects any identification as a political filmmaker, vigorously resists the discovery of political allegories in his films, occasionally provokes the leftist sensibilities that so often claim a monopoly on political filmmaking as “engaged” cinema, and so on. On the other hand, his films represent a direct and even systematic treatment of blatantly political themes and topics. One obvious, if plain, example: his recent feature-length documentary, Into the Abyss (2011), and accompanying series called On Death Row (2012–13), are a sustained meditation on and quiet case against capital punishment. But there are subtler and more profound, examples. Take his two most prestigious films, Aguirre (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982). Critics have interpreted Aguirre (considered at length in the section “The Small Voice of Conquest” later in this book) as an allegorical or metaphorical reference to the Third Reich and to the US invasion of Vietnam, interpretations that Herzog has variously discarded as unwarranted extrapolations or simply beside the point. But modern allegories aside, taking Aguirre solely in the terms of its historical referent reveals a film that could not be more deeply political: it is a story set during, and representing aspects of, the invasion and conquest of the New World by Europeans. Fitzcarraldo (considered at length in the section “I’m planning something geographical …”), always remembered as the film in which a ship was pulled over a mountain, is a story that rests on—indeed, is impossible without—the formalized primitive accumulation that was the fin-de-siècle plunder of America’s wilderness and inhabitants. So ultimately we have before us, on screen, for all to see, two of the most dramatic restagings of the historical ground that forges and sustains our political modernity, and yet there is a strong critical resistance to reading Herzog’s films politically (beyond, that is, the denunciations of his production practices; a political topic, to be sure, but in another way). It is as if the director’s own speech overdetermines the critical treatment of his work. And this weird resonance between political intensity and analytical silence, in turn, makes the aesthetic, narrative, and cinematic dimensions of his work more compelling, more mystifying, more urgent, and more psychologically complex.

In these pages I start from the premise that a central impediment to interpreting Herzog’s work is the fact that his navigation of the political defies our basic categories of left-right, progressive-reactionary, liberal-conservative, individualist-collectivist, and so on. Placing the director’s commentary to one side, the films in and of themselves are true to this unexpected treatment of the political. It is not so much that the films actively deconstruct the ordering binaries of contemporary social life. It is rather that they simply refuse these binaries and seem to operate outside, or alongside, their discursive conventions. So, in Aguirre, we have the most disturbing portrait of fevered conquest ever brought to the screen, and yet the empire (the Spanish Crown) and its opponent (the collapsing indigenous civilizations) are only marginal players, secondary, even tertiary, to the quiet battle between a megalomaniac and a jungle. Fitzcarraldo, motivated by capitalist expansion and resource accumulation, turns out to be not a competition over land, but rather over dreams. As with many prominent directors, the center of Herzog’s work is power: its circulation, distribution, accumulation, application, negotiation. But his originality rests on the way in which he upsets our expectations of its representation. The protagonist of Cobra Verde (1987), a unique, mesmerizing, and profoundly creepy story of the Atlantic slave trade (see the section “Black God, White Devil”), is a slave driver. And his “heroism” (a loaded term, and inapplicable here) does not reside in taking a brave stand against a despicable crime of capital and state, perhaps motivated by some sort of revelation that will lead to redemption. Rather, his protagonism is pure pathos, the fact that he was there to witness the crime’s exhaustion; he watched the institution die as it limply gazes toward America, bloated and washed up on an African beach as a maimed figure looks on, ascetic, largely indifferent. Critically, this kind of operatic stylization and narrative collapse is an opportunity to explore the contradictions of the film. And yet, it is simultaneously quite challenging to deal with. My sense is that the surprising lack of critical analysis of the political—not to be confused with the merely controversial—in Herzog stems from the fact that, before these kinds of images, we simply don’t know what to say. This is not because there is nothing to say. Rather, the lack of analysis arises from the difficulty of rethinking the foundational themes of our modern political imagination when they are rendered so radically unfamiliar. It is in this gesture that the (ongoing) significance of Herzog’s work resides.

Herzog’s output is vast, and one day there will be multivolume considerations of his work and life. For now, and as a way of handling the dauntingly prolific material of Herzog’s filmography in a single volume, in this book I rest the political question against the idea of America in Herzog’s work. Doing so requires two immediate clarifications. First, I invoke “America” in the broad, hemispheric sense. And, second, I do not mean to indicate that I will be preoccupied with Herzog’s precarious status as an “American filmmaker.” Significant attention has been paid to the Germanness of Herzog’s films, and in fact, despite the director’s own artistic biography, his identity among film scholars resides largely within that specific national tradition. In the thick and comprehensive Companion to Werner Herzog (Prager 2012), for example, 18 of 25 scholarly contributors affiliate with some aspect of German studies. Significantly less attention has been paid to Herzog’s sustained problematization of the idea of America and its relation to the consolidation of capitalist modernity. And yet America—as space, discourse, and dream—is central to his most stylistically and thematically ambitious work. In a striking run of films produced over a fifteen-year period, Herzog takes up the big themes of capitalist modernity and forces us to confront them by way of America: conquest (Aguirre, 1972); migration, frontiers and economic aspiration (Stroszek, 1977); penetration and accumulation (Fitzcarraldo, 1982); and slavery (Cobra Verde, 1987). From this quartet, America, as both physical landscape and political-historical project, would become implicated directly in the exploration of man’s apocalyptic drive that guides Herzog’s more contemporary work, including his highly regarded, stylized “documentaries,” such as Lessons of Darkness (1992), Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997), Grizzly Man (2005), The Wild Blue Yonder (2005), Into the Abyss, and Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World (2016). Icarus animates all these films, and it would seem that the idea of America, its status as both dream and limit in the Western imagination, has compelled Herzog to tell and retell his story there. Taking up and reframing the political at these seminal scenes of our historical present, Herzog goes right to the core—the origin stories, the nightmares, of modern consciousness—and then restages it in maddeningly opaque terms. The maddeningness, I maintain, is the politics. It invites us to defamiliarize the world and render its dominant interpretations rethinkable. I’ve seen this in action in several classroom settings, when I have taught one or another of these Herzog films alongside films governed by much more explicit, even tendentious, politicized narratives (Sayles’s Men with Guns [1997], González Iñárritu’s Babel [2006], Morris’s Standard Operating Procedure [2008], Tarentino’s Django Unchained [2012]). The immediacy with which Herzog’s films provoke notably engaged and controversial discussions that ultimately turn on questions of power is without competition. How does this work? What is the relation between cinematic style and narrative, power and its absence, in Herzog’s films? How do these films problematize the privileged categories of Western modernity, especially in their conventional liberal mode? How do they obligate us (or not) to rethink the relations between history, capital, and domination? What are their critical possibilities, and also limits? Not a search for ideological clarity, this book asks: what are the aesthetics of the political in Herzog’s work? These are the questions that will guide our consideration of a set of Herzog’s most significant films.

When approaching Herzog from a scholarly and analytical perspective, the first and most significant interpretive interlocutor is the director himself. Herzog has directed two autobiographical films (Werner Herzog: Filmemacher [Portrait Werner Herzog, 1986] and Mein Liebster Feind [My Best Fiend, 1999]) and is the subject of six largely affirmative biographical documentaries (Weisenborn and Keusch’s I Am My Films [1979]; Blank’s two films, Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe [1980] and Burden of Dreams [1982]; Gruber’s Location Africa [1987]; Weisenborn’s I Am My Films, part 2 [30 years later] [2010]; and Golder’s Ballad of a Righteous Merchant [2017]). Two volumes of his reflections—Of Walking in Ice (2015) and Conquest of the Useless (2009)—are widely available in English and several other languages, alongside his amply published literary screenplays that correspond to his individual films. His legendary DVD commentaries are without peer, eloquent, insightful, often hilarious. He has been uncommonly generous with his availability for interviews, a number of which are famous—including one during which he gets shot by a random assailant—and form a kind of Herzog canon on YouTube. The remarkable and extensive interviews conducted for Herzog and Cronin’s Herzog on Herzog (2002; expanded as Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed in Herzog and Cronin [2014]) stand as a significant work of literature in their own right and are a major source (the single most significant source, I would say) of citatio...