![]()

CHAPTER 1

Beginnings

Barnett's great-great grandparents were free Negroes in antebellum Raleigh, North Carolina. His father was a hotel worker in Florida who learned enough Spanish on frequent trips to Cuba that he was able to supplement his income as an interpreter at a plush hotel on the St. Johns River. His mother, Celena Belle Barnett, was a native of Lost Creek, Indiana.

Shortly after his 1889 birth in Florida, Barnett was brought to Mattoon, Illinois, to live with his maternal grandmother, where he grew up, eventually attending schools in Oak Park and Chicago. A friend of his mother secured a job for him when he was twelve years old with the Sears family, which presided over a major retail enterprise. “I admired him tremendously,” he said of his prime patron “and he not only talked intimately with me but used to give me tickets to theater and concerts.” Sears was thought to be “colored” by many Negroes because his mail-order system of purchasing goods, which Barnett was to emulate in one of his first businesses, undermined plantation stores and their high prices. It was at the Sears home that he met Julius Rosenwald, a major philanthropist.

Barnett entered Tuskegee Institute in 1904, still under the deep influence of Booker T. Washington, who left a profound impression upon him. Then it was back to Chicago after his 1906 graduation, where he found employment in the post office. There, he recalled later, during the ordinary course of business, he saw “thousands of newspapers, magazines and advertising…. I found myself studying them for longer periods of time” and the seed was planted that this was a business he should enter. Not yet twenty, his future plans had not yet congealed, however, as he continued to harbor dreams of becoming an engineer. But even then he had an entrepreneurial sense, evidenced in 1913 at the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, when he produced a series of portraits of famous Negroes and others, which were snapped up at a dollar each, providing a comfortable cushion of income. This provided the capital for him to organize a mail-order business in his uncle's garage that distributed portraits of famous Negroes. From there he began selling advertising space to newspapers.

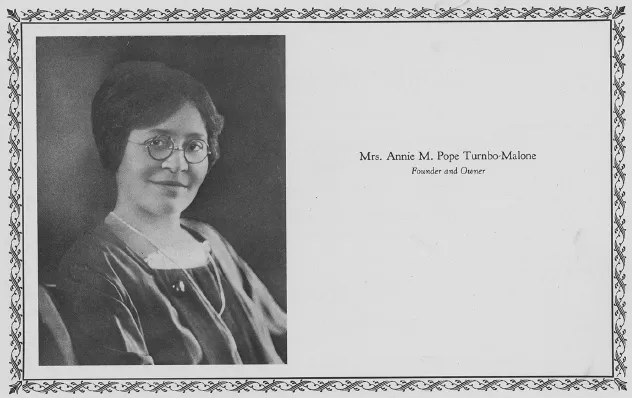

Annie Malone, a leading African-American entrepreneur, worked closely with Barnett from her headquarters in St. Louis. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

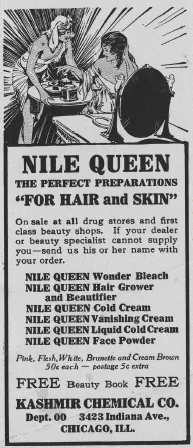

By 1918 he was working nights in the post office and selling ads in the daytime, but then he moved to initiate Kashmir Chemical, a cosmetics company, the name emerging, he said, from “having heard or read somewhere that the most beautiful women in the world live in Kashmir.” There was plenty of competition, including the eminent Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone, but the inventive Barnett lured a number of popular entertainers, including Ada “Bricktop” Smith and Florence Mills to appear in his advertisements. The business was wildly successful, to the point that Colgate's Cashmere Bouquet after charging consumer confusion, pressured him to change the name of this product to “Nile Queen.” That change, however, contributed to the product's demise.

It was also in 1918 that the tall, lanky, and dark-skinned Barnett headed westward, spending three months arranging appointments on behalf of the Chicago Defender. In every city along the way, he encountered editors complaining about obtaining news. He sped back to Chicago, retired from the post office, and asked Robert Abbott, the patron of this periodical, for funding for a news service. Abbott balked. But he arranged a deal instead whereby Kashmir received ad space in newspapers and the newly born Associated Negro Press (ANP) got capital in return. The ANP was modeled after the Associated Press; thus all papers receiving the service were asked in return to submit items to be shared by others. There also were ANP correspondents and stringers who supplied copy regularly. Barnett recollected that news-hungry newspapers “virtually stood in line” to sign up. “Several publishers,” he said, “agreed to swap advertising space for ANP service” and “Kashmir Chemical Company benefited” as a result.

Nahum Brascher, a Cleveland journalist who had worked for President Warren G. Harding, came aboard, bringing numerous contacts with him. Brascher brought panache too, as he rarely left home without an elegant walking stick and an ever-present cigar, which, along with a stentorian voice, gave him a certain presence. At the end of the first year, 80 of an estimated 350 Negro newspapers had joined the ANP. Perhaps because of Brascher's influence, the ANP also received an endorsement from Harding. By 1920 ANP and Brascher offered Republican politician and former military hero Leonard Wood their services as publicists in Wood's attempt to receive the Republican Party presidential nomination. Wood lost and owed them $4,000 for their services, leading Brascher to appeal to the son of famed evangelist Billy Sunday to wield his influence to ensure payment, but to no avail. Then they turned to Wood's mentor—Colonel William Procter of the rising consumer products company Procter and Gamble—and were successful in wheedling money out of the campaign. This led to an agreement with the Republican Party to work on Harding's behalf, and this, in turn, led to contacts with other leading Republicans, including Herbert Hoover, whom Barnett admired, and Calvin Coolidge, who rubbed Barnett the wrong way.1

Barnett had toiled on Wood's behalf, admitting in 1920 that the ANP had planned to “carry in the…weekly news service…approved articles favoring Gen. Wood.”2 His allied firm, C. A. Barnett Advertising, which was housed in the same office as the ANP on Clark Street in Chicago, had plumped openly for Wood.3

Barnett had entered a field that had yet to exhaust its full potential. As early as 1880 Negro editors and publishers banded together to advance their common interests. In 1883 the Washington Bee had sought to organize a news bureau to broaden the paper's coverage beyond the merely local. By 1910 Chicago alone was supporting fifteen Negro newspapers, as it was estimated that as many as 70 percent of Negro families there bought at least one of these journals.4

Despite the untapped potential, the ambitious Barnett initially sought to provide a service that was not limited to the Negro press. He had sought to recruit white-owned periodicals in Nashville and Columbia, South Carolina, but they were uninterested and thus missed the opportunity to receive the ANP's carefully curated news packet that was dispatched with major news on Fridays and general news on Mondays, just in time for the Wednesday deadline for publication observed by many of their clients.

Nevertheless, his business plan pointed to the hundreds of Negro periodicals that the ANP could draw upon that would be buoyed by the growing number of businesses emerging in Black America.5 “Their businesses increased in the period of freedom by 588,000,” he said in 1920, while the “per cent literate” in this community was 80 percent. The “value of church property [was] $85,900,000,” he estimated, indicative of a wealth that could be built upon. Illustrative of the importance of the Negro press was the greater attention it was receiving from the U.S. attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, who was concerned that it was becoming a vector for radicalism. This too figured into Barnett's calculation on the reasonable assumption that such concern was an indicator of importance: “During the last year,” said Barnett in 1920, “for the first time in history the office of the [A.G.] made a special investigation and public report of the Colored Newspapers of the country.” Palmer thought that “agitators of the Radical Socialist Revolutionary conspiracy have devoted time and money and thought toward stirring up a spirit of sedition among the Negroes in America.”6

Palmer may have been reassured if he had gotten a peek at ANP's correspondence with the Pullman Company, which employed numerous black workers as railway porters. The company was unhappy about the agency's coverage of unrest among these laborers, but ANP was unmoved: “Colored men broke the strike,” it observed neutrally about a recent job action, “but the company has now turned its back on them,” as the “foremen use every means to force us out.”7 It was unclear what role was played in the ANP's opportunistic position by the fact that the agency was planning a publication aimed at Pullman workers8 and hotel waiters9 with no discernible leaning to the left.

Barnett was torn when it came to dealing with unions. He was attracted for class and financial reasons to captains of industry, such as Firestone and Ford, but he could hardly ignore porters and waiters, a bulwark if the drift to the extreme right—which could imperil him too—was to be arrested. Thus, in 1934 Barnett, along with P. L. Prattis, then of the ANP, were to be found at a sizable “get together gathering” of “organized groups of Colored Railway Unions of America,” convening at the Hotel Vincennes in Chicago.10

Assuredly, Barnett was ambivalent—at best—about the rise of unions, be they railway porters or auto workers.11 When an organizing drive took place at a critical plant of the Ford Motor Corporation in Dearborn, Michigan, he argued that the company provided “Negro workmen one of the finest opportunities they have.” Keen to capitalize on “opportunities” himself, Barnett took the time to send Ford executives “enclosed stories” hailing their (alleged) good works and added, “I wish to propose a plan” that “will do much to overcome the efforts of the CIO [Congress of Industrial Organizations, the union] insofar as colored workers are concerned.” He proposed further to report on the “fallacies” of the CIO drive and the “advantage of [Negroes] remaining loyal” to the company,12 because he was lukewarm toward this campaign and other unions.13 But “Henry Ford,” the CIO antagonist, Barnett chortled, “is one of the great present day benefactors of the Negro race”; hence, the Ford automobile “should be universally the car for the average Negro buyer.” Seemingly, the ANP was willing to accept presumed emoluments in return for favorable press coverage.14

***

Because it scoured newspapers nationally and solicited articles from subscribers to its service, the ANP was also capable of providing a more capacious view of Jim Crow than most Negro journals. Of course, this was a particular concern of Barnett personally because his various business ventures often involved traveling by segregated trains.15 He was right to be concerned when he found that the “Rock Island between Houston and Dallas has the lousiest arrangement I have ever seen on a railroad, a luxurious new streamliner with two seats in the baggage car to accommodate Negro passengers.”16 If there was any consolation, it was not just Barnett who faced this indignity. His congressman, Arthur Mitchell, informed him that “Mrs. Marjorie Joiner, a highly respected business woman in Chicago [was forced] to ride in the baggage car” too, but in her case “with a corpse” when “passing through Texas.”17

There was a concordance between and among Barnett's various business interests in that there was an even larger market abroad for cosmetics than at home. He had a soft spot for cosmetics, as his Kashmir venture suggested. “About thirty five years ago after some experimentation,” he said in 1933, “the idea of using irons on kinky hair was discovered. I don't know who made the first discovery,” he said, “but it seems well authenticated that Mrs. [Annie] Malone was the first to successfully commercialize the idea” and that “Mrs. [C. J.] Walker was an agent of hers” in a business in which “profits were huge.”18

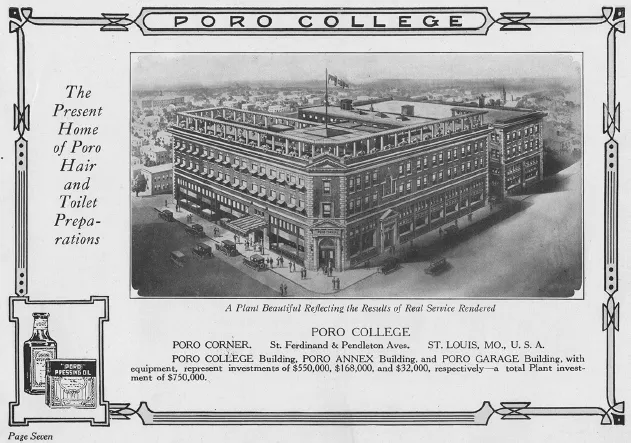

Thus, with little apparent awareness of the social and psychological aspects of hair straightening, particularly among women, the ANP lavished positive press coverage on these fellow entrepreneurs. Edna Oyerinde was tied to Malone and by 1927 was marketing her products in Nigeria. Malone's Poro College was already established in eastern and southern Africa. Like Barnett, Malone was a Pan-Africanist of sorts, and classes at Poro College often opened with a recitation of Paul Laurence Dunbar's “Ode to Ethiopia.”19 Malone and Barnett cooperated on West African investments.20 At this point, Malone was more active abroad than Barnett, for as early as 1922 her Poro College boasted of “enthusiastic agents in every state in the United States and in Africa, Cuba, the Bahamas, Central America, Nova Scotia and Canada.”21 The ANP was kept abreast of Malone's varied activities, for example, her European tour in 1924.22

Poro College, controlled by Ms. Malone, was a major client of Barnett's. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

This hair-care product was developed by Barnett as he first launched his entrepreneurial career in the aftermath of World War I. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Barnett already had announced that the “salvation of the little group of capitalists which the race boasts,” and of which he was a member, “lies in developing an absolutely independent press”; that is, his overall business interests turned on the success of his ANP. As early as 1928, however, Barnett was told that “colored people have already lost control of the Negro press.” This was a shaky assertion based on the idea that the soon-to-be defunct “Chicago Bee is subsidized to the extent of $3000 weekly by the Overton interests.”23 Still, this assertion was an early indication that non-Negroes smelled the profits to be made in this realm, which signaled what was to come. Certainly, Barnett and his “little group of capitalists”—to a degree—benefited from the captive market that Jim Crow delivered, while chafing at the repetitive indignities of such seemingly ordinary activity as taking a train. Ironically, when Jim Crow began to erode, so did his hold on a captive market.

Barnett's own difficulties with Jim Crow at home also gave him added incentive to pursue opportunities abroad. Like many African Americans—before and since—he found that this praxis of prejudice seemed to be more inured in his homeland and, as well, when it did materialize overseas it was often at the behest of Euro Americans. Moreover, glo...