- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sojourner Truth's America

About this book

This fascinating biography tells the story of nineteenth-century America through the life of one of its most charismatic and influential characters: Sojourner Truth. In an in-depth account of this amazing activist, Margaret Washington unravels Sojourner Truth's world within the broader panorama of African American slavery and the nation's most significant reform era.

Born into bondage among the Hudson Valley Dutch in Ulster County, New York, Isabella was sold several times, married, and bore five children before fleeing in 1826 with her infant daughter one year before New York slavery was abolished. In 1829, she moved to New York City, where she worked as a domestic, preached, joined a religious commune, and then in 1843 had an epiphany. Changing her name to Sojourner Truth, she began traveling the country as a champion of the downtrodden and a spokeswoman for equality by promoting Christianity, abolitionism, and women's rights.

Gifted in verbal eloquence, wit, and biblical knowledge, Sojourner Truth possessed an earthy, imaginative, homespun personality that won her many friends and admirers and made her one of the most popular and quoted reformers of her times. Washington's biography of this remarkable figure considers many facets of Sojourner Truth's life to explain how she became one of the greatest activists in American history, including her African and Dutch religious heritage; her experiences of slavery within contexts of labor, domesticity, and patriarchy; and her profoundly personal sense of justice and intuitive integrity.

Organized chronologically into three distinct eras of Truth's life, Sojourner Truth's America examines the complex dynamics of her times, beginning with the transnational contours of her spirituality and early life as Isabella and her embroilments in legal controversy. Truth's awakening during nineteenth-century America's progressive surge then propelled her ascendancy as a rousing preacher and political orator despite her inability to read and write. Throughout the book, Washington explores Truth's passionate commitment to family and community, including her vision for a beloved community that extended beyond race, gender, and socioeconomic condition and embraced a common humanity. For Sojourner Truth, the significant model for such communalism was a primitive, prophetic Christianity.

Illustrated with dozens of images of Truth and her contemporaries, Sojourner Truth's America draws a delicate and compelling balance between Sojourner Truth's personal motivations and the influences of her historical context. Washington provides important insights into the turbulent cultural and political climate of the age while also separating the many myths from the facts concerning this legendary American figure.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9780252093746Subtopic

Historical BiographiesPART I

Bell Hardenbergh and Slavery Times in the Hudson River Valley

Thus saith the Lord: A voice was heard in Ra’mah, lamentation, and bitter weeping; Ra’hel weeping for her children refused to be comforted for her children, because they were not.

—JER. 31:15

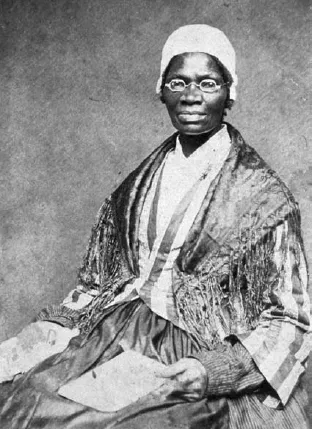

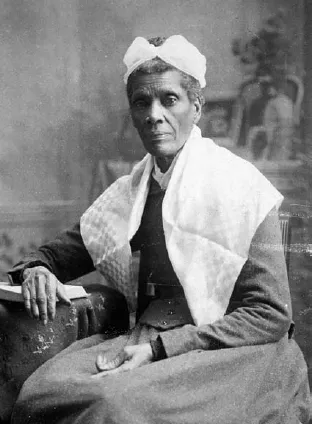

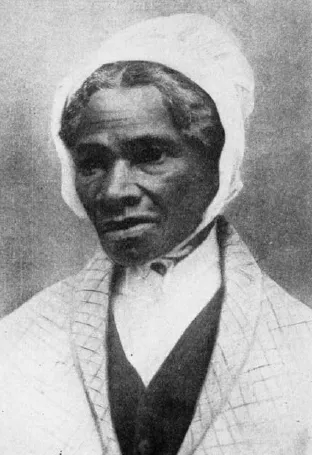

Sojourner Truth in Detroit. Sojourner’s Detroit Quaker friends promoted a refined domestic image. Burton Collection, Detroit Pubic Library.

Laura Haviland, Sojourner’s Michigan coworker, with slave irons. Haviland Papers, Michigan Historical Collection, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

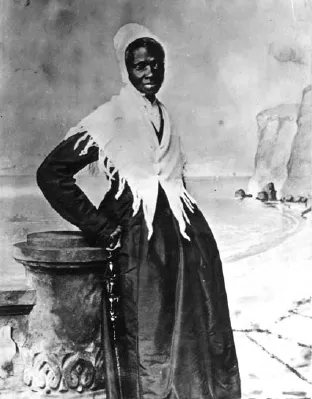

Sojourner Truth in 1850. Author’s personal collection.

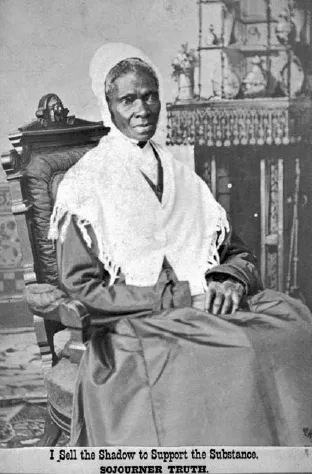

Sojourner Truth, seated—wearing black dress and shawl: “I Sell the Shadow . . .” Chicago History Museum.

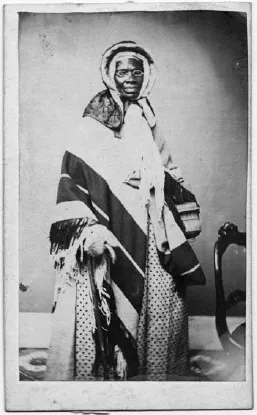

Sojourner Truth in patriotic red, white, and blue, with copies of documents in her lap. Community Archives of Heritage Battle Creek.

Diana Corbin, Sojourner’s eldest daughter. Community Archives of Heritage Battle Creek.

Frances Titus, Sojourner’s Battle Creek biographer and friend. Community Archives of Heritage Battle Creek.

Last photo taken of Sojourner Truth, March 1883. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research and Black Culture, New York Public Library.

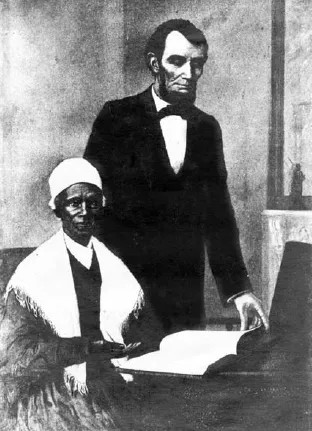

F. C. Courter, Abraham Lincoln and Sojourner Truth. Painted from their photographs (Diana Corbin modeled for Sojourner’s hand). Burton Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Mary Ann Shadd, activist, editor, friend of Sojourner Truth. National Library and Archives of Canada, Ottawa.

Gilbert Haven, Methodist bishop, radical Abolitionist, Sojourner’s friend and Northampton neighbor. Special Collections Library, Drew University.

Sojourner Truth wearing the attire from her Indiana Civil War campaign. Sojourner signed the back of this image. Chicago History Museum.

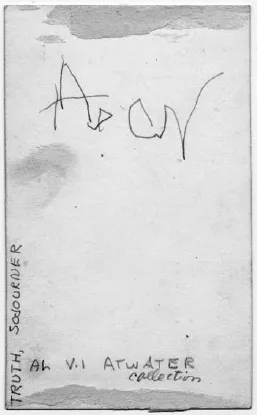

Sojourner’s first known signature (around 1863), written on the back of her carte de visite. Chicago History Museum.

I have been sent from God to your head to preach to the people. — BEATRIZ KIMPA VITA

As Oliver Cromwell put it, the Dutch preferred “gain to godliness.” — SECRETARY THURLOE

CHAPTER 1

African and Dutch Religious Heritage

I

“I am African,” Sojourner Truth told an audience. “You can see that plain enough.” Traveling the antislavery circuit, facing detractors as well as supporters, Sojourner acknowledged ties to the Motherland even as some whites declared her race to be descended from “monkeys and baboons.” She was not born in Africa. However, her maternal grandparents were first-generation “salt water” people who experienced the brutal Middle Passage, “seasoning” into a new culture, and another world. Truth’s mother-in-law always spoke broken English. On the Abolitionist platform, Sojourner sometimes shared with her audience stories of Africa told by her husband’s mother.1

When Sojourner was born, in 1797, slavery flourished among the rural Dutch who owned her family. Her mother named her Isabella, and she was nicknamed Bell. Isabella’s unusually tall father, James, was nicknamed “Bomefree,” merging the Dutch word for tree (bome) with the English word “free.” Africans from the inland Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) were very tall, and this region was the second major European trading station. The tallest Gold Coast Africans were mainly of esteemed, militaristic Denkyira or Ashanti ethnicity. Sojourner’s father was known as an honest, dependable, and hardworking bondman who possessed the proud spirit that Europeans insisted Gold Coast Africans (called Coromanti) exhibited in great measure. They were “intrepid to the last degree,” one slaveholder said. “No man,” he insisted, “deserved a Coromanti unless he treated him like a brother.”2 Isabella, nearly six feet tall as an adult, inherited her father’s impressive physical stature, strength, and height. Bomefree also reportedly was half Mohawk Indian. Ohio Abolitionists first mentioned this in 1851, and the story persisted from then on. In 1880, Eliza Seaman Leggett of Detroit wrote about Sojourner Truth in a letter to Walt Whitman, her former Long Island neighbor. According to Leggett, Sojourner “greatly admired” Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and her “father’s mother was a squaw.”3

Sojourner’s mother, Elizabeth, was “Betsy” to white adults and “Mau-mau Bet” to black and white children in the household. Elizabeth’s heritage was most likely that of West Central Africa—the region of Kongo, north of Angola. The Dutch purchased Africans from that area from the Portuguese, who controlled commerce with Kongolese traders. In the seventeenth century, Africans serving the Dutch in America (New Netherlands) learned Indian languages, and became traders and interpreters. After the British conquest (in 1664) changed New Netherlands to New York and New Jersey, Kongo peoples still dominated the North American enslaved population. By the mid-eighteenth century, civil wars had transformed a once strong Kongo monarchy into groups of politically autonomous, rural-based city-states. Around the same time, New York experienced a surge in economic growth, demand for labor, and carrying trade directly from Africa. African elites and traders were the middle men in the African domestic trade. Merchant caravans, “fairs,” and systems of regional markets and coastal entrepôts filled Portuguese traders’ coffers with ethnic people generically called BaKongo, whose main language group was KiKongo. Sojourner’s grandparents fell victim at this time to the slave trade.4

Colonial New York contained the North’s largest enslaved population; it grew by 70 percent between 1750 and 1770. By then, merchants imported captives directly from Africa to discourage entry of “refuse and sickly Negroes” and because colonial vessels coming from Africa paid lower duties. American “sloops”—small, swift, seaworthy vessels—conducted a triangular trade. They transported Hudson Valley foodstuffs to Caribbean and Carolina markets, then carried furs and lumber to England, and then returned to America with Holland duck, housewares, rum, sugar, and Africans. Some New York City families traded with Africa directly and had mercantile collaboration with Ulster County elites. Traders maneuvered their sloops up the Hudson, trading black captives for Ulster’s renowned agricultural products, destined for urban markets or West Indian plantations. Isabella’s owners were local merchants, gentlemen farmers, and customers of these traders.5

The work Africans performed in America—the gendered divisions of labor and the structures of household economy—was not completely unfamiliar. African village life centered on agriculture and herding. Men and boys performed the heavy arboricultural tasks, tended herds, built homes, hunted, and fished. Men also conducted long-distance commerce and monopolized artisan skills. Women and girls tended to household animals, did domestic chores, and oversaw the land’s agrarian gifts. Women had more independence on the coastal littoral. Some produced luxury items, including salt derived from seawater. Others dove for seashells, the most valuable of which (nzimbu) were thin, brilliantly black, and the currency mainstay of the slave trade. Both sexes frequented local markets to sell goods and exchange regional specialties. Dutch New Yorkers wanted women for domestic labor, and children they could train; a large proportion of women figured into the British trade, and West Central Africa exported the largest number of youth. “For this market they must be young,” a New York merchant cautioned; “the younger the better if not quite children.”6

Sojourner Truth’s African-born grandparents provided a connection to the spirituality and cultural provenance of the Motherland, most likely BaKongo, and a crude exposure to Catholicism. Throughout Kongo, the Portuguese set up chapels, where Africans catechized their own people. However, only whites administered the sacraments, baptizing captives with a pinch of salt and bestowing Christian names before shipment. Dutch Calvinists, who hated anything Catholic, would not use the name Isabella. Yet Isabella was the name of a female saint revered in Kongo, and the name of the militant sister of the Kongo king Pedro IV. Africans generally named their children after ancestors, grandparents, and even living parents. Thus, Isabella may have been the name of Sojourner Truth’s grandmother. It is also intriguing that the naming practices of Sojourner’s mother, Elizabeth, differed from less numerous West African ethnic groups in New York, who recycled Akan names such as Cuffee, Kofi, Mingo, and Quashee. Both naming practices reveal autonomous ethnic socialization, but only Isabella’s suggests a West Central African heritage and Catholic influence.7

Young Isabella may not have known her African grandparents. But they made the Middle Passage like countless millions, in a state of bone-chilling emotional shock that was mitigated only by reforging new cultural bonds. Isabella certainly heard stories of the homeland from her mother and later from her mother-in-law. Memory and oral history were major links with the past for nonliterate folk, facilitating adjustment to new environments, community formation, identity grounding, and construction of new lifestyles. Geography separated Africans from their Motherland, but the routes to American slavery during the Atlantic trade era operated as “a series of cultural highways” that connected the enslaved in America to transatlantic societies of Africa.8

Isabella’s verbal gifts and remarkable recall were reminiscent of an African griot (an oral historian and storyteller) and symbolic of her leadership. She also embraced spirituality long before embracing Protestantism; even after her Christian conversion, she claimed clairvoyance and a “second sense.” African Americans called it being “born with a caul”—the fetal membrane or a special body mark or imaginary veil representing supernatural insight. Historians’ recorded evidence of African female leadership enriches our understanding of the non-American contextual heritage that may have impacted Isabella. Her African homeland produced priestesses, prophetesses, queens, and female warriors. Some cultures were matrilineal and celebrated earth mothers; in others, women engaged in civic and commercial enterprise. In Kongo, prior to Catholicism, female authority was recognized through powerful matrilineal descent groups and cults of social formation called kanda. They represented a central source of collective female influence, symbolized by controlling land use, labor, and production distribution. Kanda political authority included selecting chiefs and cochiefs.9

Even after the Portuguese introduced Catholicism, women in Kongo were ngangas—diviners and priestesses with special access to God, called Nzambi. As Other World mediums and channels to supernatural knowledge, ngangas dispensed positive sacred medicine (called nkisi) and had the power to invoke harm, or kindoki. After Catholic priests outlawed as heretics all ngangas except themselves, women continued to assert their power through revitalization movements. Beatriz Kimpa Vita, a revered nganga, challenged the Catholic Church and Kongo elites by opposing the slave trade, leading a massive reunification movement, and embedding Kongo cosmology within Catholicism. Beatriz’s influence was so unassailable that even after she was burned at the stake twice, to deter followers from retrieving her bones for amulets, her movement continued.10

Beliefs, memories, stories, and legends that traveled with Africans on the Middle Passage were repeated and reinvented in Dutch New York and elsewhere. These chronicles endowed the people’s spirits and enriched their survival impulses. Such remembrances would have included narratives about powerful women. Given Sojourner Truth’s African heritage, the sacred authority and strength of the Motherland’s women should not be separated from the substance of Sojourner’s character and social justice mission.

II

“I was bred and born,” Sojourner Truth said, “if I was born at all, in the State of New York, among the Low Dutch people.” The large stone house in Ulster County where she began life still exists, as does the little hamlet of Hurley, with its quaint, bucolic architecture from another time. Hurley is nestled in the valley of the Esopus, where rushing local waterways wind into the majestic Hudson River. “There were no railroads, or steamboats, or telegraphs when I was born,” she added. “There were only horses, wagons, oxen and sloops.”11

Ulster County, a rural backwater 50 miles north of New York City, could not claim the ethnic diversity of the latter, where even in the colonial era some eighteen languages were reportedly spoken. However, Palatine Germans, French Huguenots, and Walloons settled in Ulster early on and melted into the numerically dominant Dutch via language, religion, and marriage. Nor did the British conquest alter the mid–Hudson Valley’s Dutchness, although some place names changed from Dutch to English. Only after the American Revolution did an influx of New England settlers and war veterans produce a more Anglo-American character.12

People of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- A Word on Language

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: The three Lives of Sojourner Truth

- Part I Bell Hardenbergh and Slavery times in the Hudson River Valley

- Part II Isabella Van Wagenen: A Preaching Woman

- Part III Sojourner Truth and the Antislavery Apostles

- Epilogue: Well Done, Good and Faithful Servant

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sojourner Truth's America by Margaret Washington in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.