![]()

PART I

FREE BLACK COMMUNITIES

![]()

CHAPTER 1

ROCKY FORK, ILLINOIS

Oral Tradition as Memory

Communities as old as Rocky Fork carry a large measure of oral tradition and memory. Accounts of the settlement’s activism survived through oral tradition, memory, and newspaper stories, as well as recollections of local families and communities. With much of their history standing outside traditional Underground Railroad narratives, residents were careful to preserve vital elements of the history of the Underground Railroad and of African American self-determination on the nineteenth-century midwestern frontier.

Remnants of the free Black settlement at Rocky Fork lie deep in the woods, rolling hills and pastures, and dramatic rock outcroppings of Godfrey, Illinois. Rocky Fork has an importance beyond its historical narrative. The humanity of the men and women shines through in a variety of sources, revealing names, physical descriptions, lifeways, family connections, and community bonds.

An early twentieth-century newspaper article captured the essence of the enclave just off Grafton Road, “set back and far away from habitation, just at the fork of two streams which give it its name.” Rocky Fork’s huge glacial boulders mark the rugged land, rendering much of the area unsuitable for farming, although by necessity, Black farmers tilled every usable acre.1

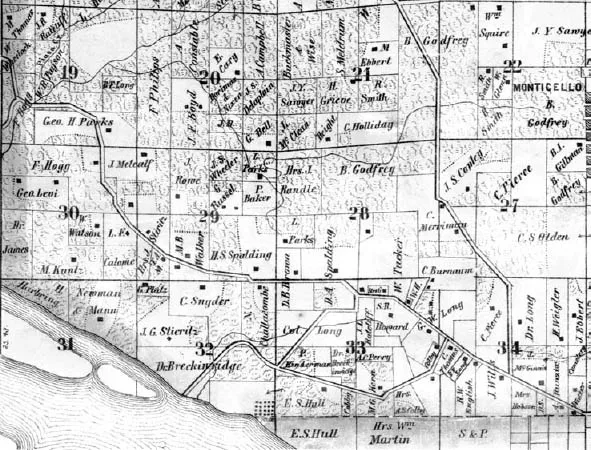

Four Black families purchased adjacent parcels in the heart of Rocky Fork drainage basin, marking the formal beginning of the Rocky Fork community (map 2). The loosely defined boundaries of the settlement shifted over time according to landownership and attendance at the small local AME church. The rebuilt Rocky Fork AME church, a few foundations, and the original terrain are all that survive of the small settlement situated approximately three miles west of Alton, a major Underground Railroad station and one of Illinois’s main abolitionist centers (see map 1).2

Map 2. 1861 Plat map, Madison County, Illinois. 1861 Plat prior to construction of Rocky Fork Church showing names of G. Bell in Section 20, L. Parks in Section 28 and 29, P. Baker in Section 29, and D. A. Spaulding in Sections 28 and 33. 1861 Map of Madison County, Illinois. Holmes and Arnold, Civil Engineers and Map Publishers. Buffalo, NY.

Surrounding rivers and intersecting creeks soften the inhospitable contours of the land. Rocky Fork Creek, a small tributary accessible from the Big Piasa Creek, flows through the once thriving settlement. The creek empties into the legendary Mississippi River, affording anonymity and quiet accessibility to those escaping slavery along the border between the free state of Illinois, and Missouri, a slave state. In the years before the Civil War, the river and the Black workers who navigated it were vital partners on the Black pathway to freedom.3

Geography, politics, and location played major roles in populating the original settlement where the river and surrounding waterways facilitated escape from slavery. Rocky Fork’s accessibility from the Mississippi River, to the Big Piasa Creek, to the Rocky Fork Creek, marked the area as a suitable stopping point for escapees from slavery—a secluded, safe refuge, a first stop in the North for those making their way out of slavery via the Kentucky route or crossing to freedom from Missouri. Escapees were in the Rocky Fork area as early as 1816, and free Blacks found the nearby town of Alton a tolerable place to live as early as the 1820s.

The abolitionist center and Underground Railroad town of Alton played a powerful role in the fight against slavery in the region. The town commanded an advantageous vantage point south of Rocky Fork on the Mississippi River across from St. Louis. Adding to the tensions of the region, large portions of Illinois maintained a strong proslavery stance, echoing sentiments in cities across the North. Those proslavery sentiments, however, did not stop escapees from making their way from either the Missouri or the Illinois side of the Mississippi River.4

Family Histories

The rootedness of the originating families at Rocky Fork offsets the pervasive theme of African American migration. Families and communities and their churches had been wedded to the land for more than 170 years. Ann Bell, her mother, Tisch Garnet, and her uncle, Peter Baker, in addition to London Parks, were among the earliest settlers living amid their White neighbors. Land transactions of two prominent White antislavery families, the Spauldings and the Hawleys, shaped the evolution of Rocky Fork as an African American settlement. Don Alonzo Spaulding, a county surveyor from 1825 to 1835, engaged in one of the meandering professions that provided a convenient cover, above suspicion, of Underground Railroad business. He knew the land well and executed numerous land sales. Intermarriages between the two White and the several Black families further bound the residents to one another.5

Blacks and Whites lived among one another, and Spaulding seems to have held little concern about the close proximity to African Americans or the circumstances under which Blacks obtained their freedom. He supported their work clearing his land in exchange for eventual land ownership. Fifty-two of the ninety-seven Blacks residing in Godfrey in 1855 lived in direct proximity to Spaulding; many settled on his land.

Similar to patterns found by historian Stephen Vincent in Indiana, families intermarried and tied the community together “in a confusing array of marital alliances.”6 The extended Rocky Fork family tree reveals the interconnectedness of the residents. The families of the founders intermarried. A. J. Hindman married Ann Bell’s daughter, Lucinda. Church founders Erasmus and Jane Green were the great-great-great-grandparents of Benjamin Matlock; Peter Baker, Ann Bell’s uncle, was the great-grandfather of ninety-eight-year-old Charles Townsend, whose oral testimony brought the community into focus.7

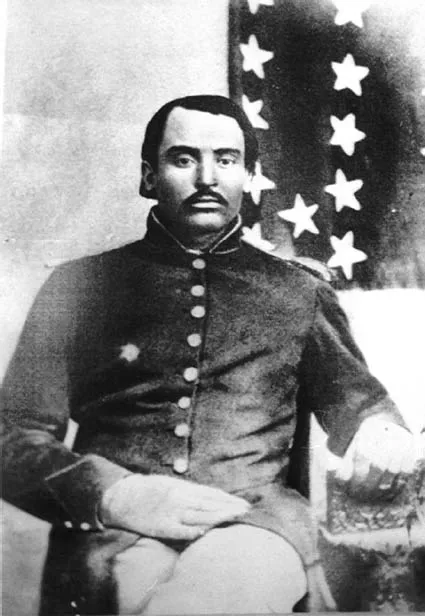

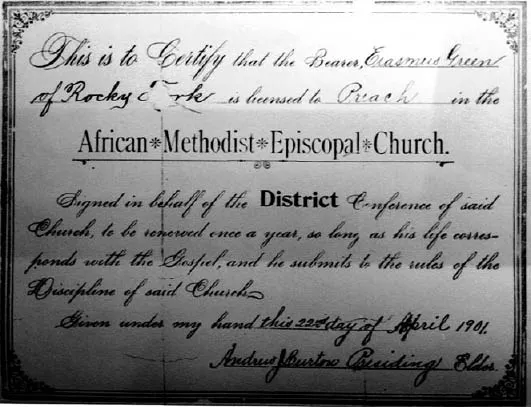

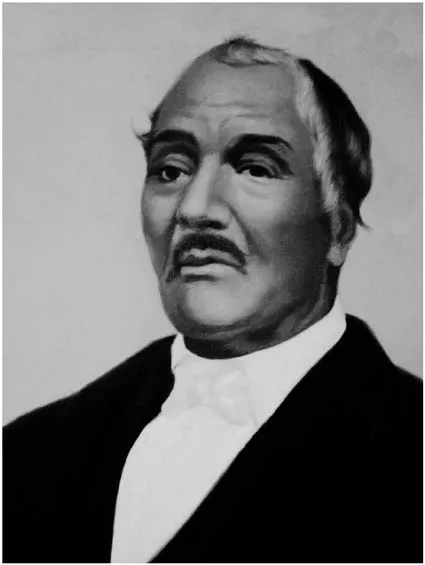

Erasmus Green, the son of his enslaver in Bolivar, Tennessee, is listed as a mulatto in the Illinois census. Both Green and Eliza Jane Duncan had been enslaved in Bolivar, where they married, before migrating to Rocky Fork upon obtaining their freedom. Green and his wife led the community in building its first church (figures 1.1 and 1.2). London Parks and his wife, Jane, important Rocky Fork landowners, also lived in the area during the first half of the century. Parks appears to have been a perceptive businessman who bought and sold several parcels of land in the community, the first of which he acquired in 1845. He and his wife stand out in the land transactions and establishment of two of the earliest AME churches in the area. In addition to Black landowners, African American farmers worked in the area.

The Spauldings and the Hawleys did choose to go against the prevailing racial attitudes existing in Illinois at that time. By 1829, the state of Illinois ruled that no Black or mulatto would be “permitted to come and reside in this State, until such person shall have given bond and security.” The state further ruled that any person who brings into the state “any Black or mulatto person, in order to free him or her from slavery, or who aids or assists any person in bringing any such Black or mulatto person to settle or reside therein, shall be fined one hundred dollars on conviction, or indictment.”8

The two families suffered no consequences from disobeying the law. According to Joseph Hindman, grandson of Rocky Fork co-founder A. J. Hindman, the Spauldings and the Hawleys gave out land to those who would clear it and pay over a period. Neither family appeared concerned about the source of freedom, whether appropriated, purchased, or granted, for the Blacks who came to them under the work-for-land exchange. Hindman continued, “the Spaulding and Hawley families set up a system of selling land to the one-time slaves, who availed themselves of the offer.”9 Local historian Charlotte Johnson reports, “When the escaped slaves came over [Spaulding and Hawley] gave them the ability to work … and as they worked for them they could move on or they could stay there and build their homes and buy property.”10 Oral accounts indicate laboring Blacks or their descendants eventually owned much of the district. Evidence of ownership was not borne out in the documentary record, however. After the backbreaking work of clearing the land, land ownership was rarely formalized or legalized and therefore little documentation of the process remains.

Figure 1.1. Erasmus Green, an early AME minister at Rocky Fork Church, in his Civil War uniform. Courtesy of the Black Pioneers Committee, Alton Museum of History and Art, Inc.

Figure 1.2. Jane Green, wife of Erasmus. Courtesy of the Black Pioneers Committee, Alton Museum of History and Art, Inc.

Figure 1.3. Erasmus Green’s AME preacher’s license. Courtesy of the Black Pioneers Committee, Alton Museum of History and Art, Inc.

Longtime resident Mr. Townsend asserts that Hawley “worked the folks pretty hard,” suggesting that altruism was not a primary motivator. Charlotte Johnson found people worked for them for a year, “made a little bit of money, bought a house and a horse so that they could move a little bit farther up the line; came back and worked for them and earned a little bit more money; moved further up the line until they moved … to Springfield and to Peoria.”11 Often the workers did not take title to the land and therefore did not appear in official records, making this type of arrangement extremely difficult to track.

Ironically, and in contrast to prevailing local and family oral histories, London Parks, a free Black man, consistently appears in land transfer records. In 1856 Parks sold a parcel of land in Rocky Fork to one of the early settlers, Peter Baker, Ann Bell’s uncle.12 Land transfer records show the central role Parks played in the development of the community although his story does not occupy an important part of local historical and family narratives. Parks’s descendants did not remain in the area. Consequently, memory of their contributions has not survived; their family history and connections to the church were not nurtured by the repeated acts of family recitation.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church

In the early 1800s, self-emancipators, runaways, and Black freed men and women heeded the call to go west in pursuit of a better life, following the same impulses that drove White eastern and southern Americans. As these pioneers populated the western frontier, formal church buildings were not yet the norm. Weather permitting, early religious services took the form of outdoor group gatherings, camp meetings, and revivals. People traveled great distances, congregating for several days to receive the word of God from an itinerant minister or preacher. Such camp meetings were very popular in the Alton-Rocky Fork area. One elderly resident, Mrs. Florence Cannon, recalled stories of campground services on the property of Ben Matlock Sr., one of the early settlers, before the settlement built its place of worship.13

An active congregation must precede the building of any church. At Rocky Fork, in addition to holding campground meetings, the congregation met in the homes of members before forming the church. “We know the people met but I don’t think they met as Baptist or Methodist until after Green became ordained,” observed local resident and historian Charlotte Johnson, referring to its first pastor. “Rocky Fork [church] was already in existence and going but it was not a Methodist church; it was just a church. Folks got together and had church.”14 One of the oldest residents, Charles Townsend, also reported religious gatherings took place in the homes of different congregants.15 Those who participated were free people of color, freed slaves, or enslaved persons, some of whom had reached “free territory via the Underground Railroad,” as one church historian observed.16

Methodists required seven or so members for the beginnings of a Methodist society, which preceded formation of an officially sanctioned church. Oral accounts identify William Paul Quinn as the presiding AME elder who transformed the society into a congregation. Apparently, Elder Quinn mentioned visiting Rocky Fork and having religious services with the people there before 1840 (figure 1.4).17

Figure 1.4 William Paul Quinn, fourth bishop of the AME Church. Courtesy of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Elaine Welch, Quinn’s only biographer, describes him as standing six feet, three inches tall and weighing 250 pounds. The Black itinerant minister was a rugged man well suited for the “Herculean task of frontier preaching.” Quinn was a traveling exhorter, or circuit rider, who “preferred half-wild horses and loved to come galloping up full tilt to places where he preached,” dismounting just as the horse stopped. He routinely traveled from Pennsylvania and Maryland almost entirely on horseback to the banks of the Mississippi River, ministering to his far-flung flock, spreading the AME Church and the word of God at least three hundred miles beyond the Missouri line.18 Quinn, who would become the fourth bishop of the AME Church in 1844, was a rough and ready man, not known for heeding the demands of racial protocol and hierarchy.

According to Welch, Quinn “helped many slaves to escape from their masters, and to find asylum in the north, away from the thralldom of the south.” Welch continues, “being a man of resourcef...