![]()

Part One

Historical Approaches to Technology and the Voice

![]()

Chapter 1

Apprehending Human Voice in the “Silent Cinema”

Julie Brown

In the silent cinema, moving pictures had no soundtracks, nor, when exhibited, were they subject to consistently applied sonic accompaniments; least of all did they have an established sound hierarchy in which voice occupied a particular place—central or otherwise. Many early moving pictures were conceived as “attractions” rather than principally as vehicles for narrative, while others—including “attractions”—involved the material visualization of sound; indeed, for Isabelle Raynauld, the latter is what permits us clearly to differentiate early from later cinema. Yet sounding voices could also be added in the moment of exhibition, at the fairground or in the theater or cinema, and this could be done in a variety of different ways. During their first thirty years, the moving pictures therefore afforded the representation of voice and vocality by means of diverse cinematic and theatrical systems.

In this chapter, I outline the many manifestations of cinematic “voice” in the silent cinema. Among others, these include speaking within a “hearing” screen world to which the audience is nevertheless deaf; intertitles; bodily gesture; typed words on the screen; live voices in the theater variously describing the moving pictures, reading out title cards, or lip-syncing dialogue or song, and so forth. I draw on Brian Kane’s reconceptualization of “voice” as Phoné to theorize voice in the silent cinema in a way that moves beyond notions of vocal silence and audience deafness. For Kane, Phoné “is distinct from three other terms with which voice is often described”: echos, topos, and logos—that is, roughly speaking, sound, site, and meaning. What Michel Chion describes as “elastic speech,” but which we can expand to silent cinema “voice,” might therefore be better conceptualized as a series of techniques necessitating a constant movement between different manifestations of echos, topos, and logos, created via various technologies or techniques (technê). Because echos is sometimes entirely absent in the silent cinema, I also draw on Nicholas Cook’s account of the inherently multimodal character of meaning apprehension, arguing that this fundamental aspect of human communication was exploited by the silent cinema such that “apprehension” is a more apt word than “listening” to describe how silent cinema’s representational systems for voice become intelligible to the viewer.

Voice in the Silent Cinema

As a first step toward theorizing early cinematic “voice,” let us start with a few observations to clarify its nature. Silent cinematic voice is resolutely different from sound cinematic voice principally because the theatrical setup is different. Michel Chion argues that in sound cinema the suture effect leads to the image governing the triage of different types of sound, including voice. We can all doubtless think of exceptions, but we would also probably recognize the typical scenario of synchronous sounds being “swallowed up” by the fiction, in the way Chion describes: you hear a sound and look for a potential screen source. In sound film, “it’s as if the voice were wandering along the surface, at once inside and outside, seeking a place to settle,” Chion suggests—“especially when a film hasn’t yet shown what body this voice normally inhabits.” In this situation, sounds “from the proscenium” or “the pit” that are not visualized on-screen gain the spotlight because “they are perceived in their singularity and isolation.”

During the first thirty years of cinema, we can assume neither the same sight and sound relationship nor the same role of voice in cinematic entertainments. Film performance (as I prefer to describe silent film exhibition) did not have an invisible apparatus. The performers involved in film screenings were almost always visible, in one way or another, and so even attempts to render on-screen voices materially in the theatrical space created a kind of “off-screen” space by default; actual off-screen sound would likewise be located elsewhere in the theater. This is in contrast to the off-screen vocal sound of sound cinema, which in most cases comes from the same actual place as the other sounds—a central loudspeaker. Sonorous voice heard in the moment of “exhibition” or early performance only rarely coincides and “locks” with the image. Because of the many forms that voice took, the early film theater would not have been conducive to sutured listening, nor to comprehension of the screen as source of sound and voice triage.

Those many forms of voice included sonorous voices heard during the moment of exhibition, what Raynauld describes as “materially visualized” voice as part of onscreen scenarios, and a range of other techniques for representing word and speech, including and exceeding those described in Chion’s account of “elastic speech.” It is useful to start with a short overview of the silent cinema’s complex representational system for voice, approaching it along two axes: one that recognizes the defining feature of silent film exhibition, namely, that voices can be both heard and unheard; another that recognizes that voices can pertain directly to a moving picture entertainment, and/or be part of the wider mixed program. As Nicholas Hiley reminds us, over the first twenty-five years of projected moving pictures “the basic unit of exhibition was not the individual film but the programme.”

Of the unheard cinematic voices that relate directly to the moving pictures themselves, most fall into the category of on-screen visual effect and can pertain to fictional worlds and nonfictional worlds or can involve direct (performative) address. In fact, early screen scenarios often involved both fictional world and direct audience address, especially comedies and other entertainments transferred to screen from the popular entertainment stage.

Material Visualization of Voice

As Raynauld and others have revealed, the human voice, speech, and sound in general were constantly present in the scenarios of moving pictures during the first thirty years, and from the first decade of moving pictures, these scenarios “took place intradiegetically in a hearing world and not in a ‘deaf world.’” This “visualized sound cinema,” as she calls it, showed or implied sound of a wide variety of sorts—from noises, to music, to voice. Films produced by Pathé 1907–1914, Georges Méliès (her particular focus), and others not only often implied sound that might go on in any “real world” situation but also included “sonorous events,” that is, actions involving sound that carry narrative information and affect the course of the scenario. As she notes, film scenarios and films themselves did not wait for technological developments permitting perfect synchronization between image and sound in order to attempt to tell stories that were simultaneously visual and sonorous.

Mouthed Dialogue

The classic on-screen visual effect for voice is that of on-screen actors speaking or singing to each other in the hearing world that is the film set. Raynauld has debunked the myth that actors generally spoke randomly on set. Interested in what early actors of the silent screen were doing when they moved their lips, she performed a comprehensive study of screenplays and films written in France between 1895 and 1915, and found that more than half of the scripted titles and stories in the Pathé catalogue that were not actualities, sports, or travel films (1,925 out of 3,346) were what she felt able to term “early sound screenplays.” Of the screenplays she was able to pair with their corresponding films, it transpired that the dialogues were indeed those “intended to be performed by the actors.” We also know that mouthed dialogue was often particular to the scene filmed because some early filmmakers wrote about asking actors to enunciate slowly and deliberately if they wished certain words to register. Although it can be difficult for the audience to lip-read what the actors are saying, often and especially with films dating from after the late aughts, the meaning of the movement of their lips is more or less deducible—especially in the case of shouts, or simple phrases. A fragment may even be recognizable in a neighboring title.

But it was not simply a matter of voice being represented in a mute medium as an accidental byproduct of the photographic capturing of both fictional and nonfictional human happenings from the “hearing world.” A remarkable facet of early films is how common scenarios in which voice and spoken word play a pivotal role were. According to the American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States (Film Beginnings, 1893–1910), even before 1910 at least ten films with “voice” in the actual title were distributed in the United States; many more included music or singing in the title (six with the word “sing” or “singing”), and dozens with music or musicians, as follows:

1905 His Master’s Voice

1906 Voice of Conscience

1907 What His Girl’s Voice Did

1908 His Daughter’s Voice

1908 A Voice from the Dead

1908 The Voice of the Heart [Italy: Aquila Films. La voce del cuore]

1909 The Voice of the Violin

1910 A Powerful Voice [Gaumont]

1910 A Voice from the Fireplace

1910 The Voice of the Blood [Itala Films]

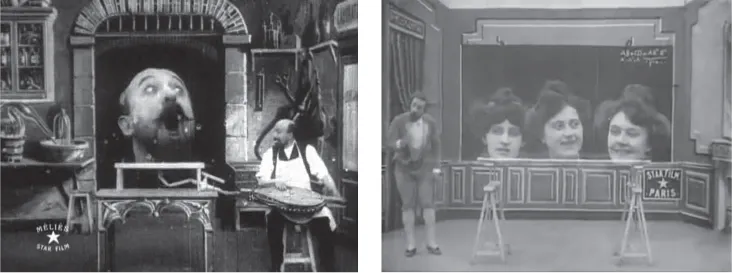

And as Raynauld reports, many of the scenarios of early French films depended upon hearing particular words, such as Pathé’s Erreur de porte!! (1904), which involves a character who hears or is told something that he would not have heard and who sees his life changed by that sound event. In several films, Méliès comically thematizes the figure of the “talking head,” which was a routine part of both spoken theater and moving pictures. The lips and head move; they are just severed from a body. In L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc (The Man with the Rubber Head) the head speaks to Méliès (Figure 1.1a), in L’Oeuf du sorcier (The Sorceror’s Egg) and in Le Chevalier mystère (The Mysterious Knight), the head likewise doesn’t stop moving, smiling, speaking to the magician (Figure 1.1b).

Figure 1.1: (a) L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc (The Man with the Rubber Head, 1901); (b) L’Oeuf du sorcier (The Sorceror’s Egg, 1902).

The 1911 Italian comedy Pik Nik ha il do di petto (Pik Nik as...