![]()

CHAPTER 1

Corrupt Illinois

PUBLIC CORRUPTION HAS BESMIRCHED Illinois politics for a century and a half. Even before Governor Rod Blagojevich tried to sell the vacant U.S. Senate seat to the highest bidder, the people of the state were exposed to outrageous corruption scandals. There was, for instance, Paul Powell, a downstater, former secretary of state, and old-style politician. He died leaving hundreds of thousands of dollars from cash bribes hoarded in shoeboxes in his closet. There were the thirteen judges nabbed in Operation Greylord who were convicted for fixing court cases.

Four of the last nine governors of Illinois went to jail—Otto Kerner, Dan Walker, George Ryan, and Rod Blagojevich. They were preceded by other governors such as Joel Matteson, Len Small, and William Stratton, who were indicted or found culpable in civil or legislative hearings but were not convicted in criminal courts and were not sent to jail.

Kerner was the first governor to be convicted of bribery, conspiracy, and income-tax evasion in a case involving racetrack stock improperly acquired while in office. Dan Walker was convicted after leaving office for bank fraud at a savings-and-loan bank he acquired.

The case of George Ryan, a pharmacist and former chairman of the Kankakee County Board, involved felonies by high-ranking officials as well as bribery committed by frontline clerks and inspectors. He was convicted of eighteen counts of corruption for leading a scheme in which bribes were paid to his campaign funds as both secretary of state and governor. Secretary of state employees sold truck-driver licenses in return for bribes that were partially given to the Ryan campaigns. This led to fatal accidents by unqualified truck drivers.

The last governor (still in prison) is Rod Blagojevich, who has become the face of Illinois corruption. Even before he was convicted, he was impeached by the Illinois legislature and thrown out of office. Similar to former Governor Ryan, he was convicted on multiple counts. He had established a corrupt network of businessmen, political appointees, and politicians. He shook down businessmen and institutional leaders for bribes. He appointed corrupt individuals to various boards and commissions to shake down hospitals, racetracks, road builders, and government contractors. He is most remembered for trying to sell off Barack Obama’s U.S. Senate seat after Obama was elected president in 2008.

But it is not only governors who are corrupt. Corruption pervades every part of the state—not every town and government office, but too many. Among the convicted congressmen, perhaps the most colorful was the swaggering Dan Rostenkowski, Mayor Richard J. Daley’s man in Washington.

Among state officials, the most well-known was the “good old boy” Paul Powell. Secretary of State Powell grew up in Vienna, Illinois, in downstate Johnson County. He was first elected to the state legislature, where he rose through the ranks to be elected speaker by a downstate coalition of legislators. From there he ascended to the secretary of state position, where, like later Secretary of State George Ryan, he would use that post to enrich himself. Although Powell never earned more than thirty thousand dollars a year, his estate was worth $4.6 million, including racetrack stocks like those Governor Kerner took as bribes. The most memorable aspect was the eight hundred thousand dollars found in shoeboxes in his hotel room in Springfield.

To round out a more modern corruption montage, there is the strange tale of Rita Crundwell, the comptroller and treasurer of downstate Dixon, Illinois. Dixon is most famous as the home of former President Ronald Reagan. Crundwell’s story illustrates that corruption is not necessarily limited to high state officials or denizens of big-city Chicago. She managed to steal an amazing fifty-three million dollars to fund a very high lifestyle over a number of years. She persisted even in recession years, when the town had to make severe cutbacks in public services. She accomplished this by the simple expedient of opening a fake checking account and transferring city funds to that account. For her crimes, she received a twenty-year prison sentence, and her horses and jewelry were auctioned off to reimburse part of the stolen funds. The media, particularly television, prominently displayed pictures of her swimming pool, home, horses, and jewelry, which average citizens in Dixon could not afford.

Corrupt politics in Illinois have always been colorful. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Chicago aldermen were paid a stipend of less than two hundred dollars a year. Yet the Chicago Record, a newspaper of the time, revealed: “In a fruitful year the average crooked alderman has made $15,000 to $20,000”—big money in those years.1

Most Chicago aldermen were on the take. In the famous “Council of the Gray Wolves,” which lasted from 1871 to 1931, the journalist and crusader William Stead wrote that no more than ten of the seventy aldermen in the council “have not sold their votes or received any consideration for voting away the patrimony of the people.”2 As the leading Democratic paper, the Chicago Herald, put it, aldermen in “nine cases out of ten [are] a bummer and a disreputable who can be bought and sold as hogs are bought and sold at the stockyards.”3

Things were no better in the state legislature. In the second decade of the twentieth century, forty state lawmakers accepted bribes to elect William J. Lorimer to the U.S. Senate. He was later thrown out of the Senate. The scandal contributed to the passage of a U.S. constitutional amendment in 1912 establishing the direct election of senators by the people rather than by the state legislatures. In the following century, Illinois residents seemed resigned to government corruption.

Times may be changing, however. Since Governor Rod Blagojevich’s indictment and conviction, a groundswell of public support for ending corruption has developed. A 2009 Joyce Foundation public-opinion poll showed that more than 60 percent of Illinois residents list corruption as one of their top concerns, even higher than the economy or jobs. More than 70 percent of Illinoisans favor a number of specific reforms. Yet such reforms get enacted only after long, drawn-out battles, if at all, because of the pervasive culture of corruption.

Separately, an Illinois Ethics Commission and a Chicago Ethics Reform Task Force have met and issued reform recommendations, and some of these have become state law or city ordinances. But corruption persists. Taming corruption in Illinois will take changing the culture of corruption in addition to the passage of ethics and campaign-finance regulations.

The Most Corrupt City in One of the Most Corrupt States

Public or political corruption occurs whenever public officials use their insider information or their official position for public gain. In some cases, infractions may seem minor, but cover-ups or the failure of officials to take corrective action only increase corruption and underline Illinois’ culture of corruption. A lot of corrupt deals in this state occur with a “wink and a nod,” overlooking the corruption that is hidden underneath.

Whether specific misdeeds by government officials can successfully be prosecuted changes over time. Generally speaking, the laws become stricter, and investigators and prosecutors improve their methods. But despite changes in law and prosecution, using a public position for private gain has always been wrong and is usually illegal. Yet, such corruption has reigned in Illinois for over 150 years.

Chicagoans, like bragging Texans, tend to revel in being the biggest or first at anything. It is part of our inferiority complex about being the “Second City.” For many years, but more intently since the colorful Blagojevich trials, we have been known as the most corrupt city in the United States. Based upon the corruption convictions in U.S. federal courts, Chicagoans can legitimately boast that we are the most corrupt metropolitan region in America.4 Nonetheless, it is shameful to be first in corruption.

The corruption-conviction statistics by which we measure these crimes are from the Federal Judicial District of Northern Illinois, which means that Chicago’s corruption data covers the suburbs, not just the evil city. In chapter 7, we report on the shocking extent of suburban corruption, which includes far more than the usual notorious suburban towns like Cicero and Rosemont.5

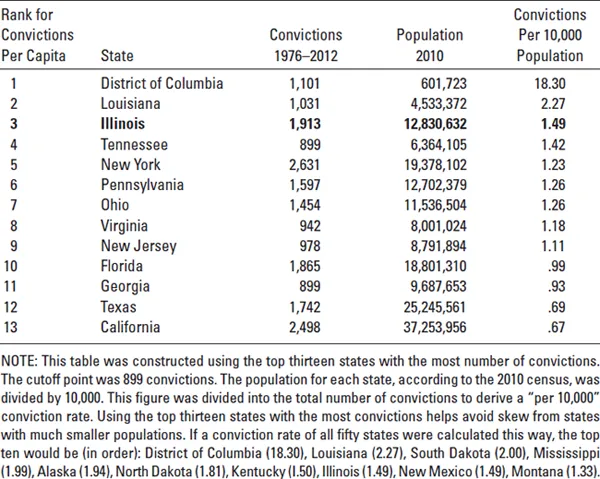

Much like its largest city, Illinois is also corrupt. It is the third most corrupt of the fifty states. Illinois’ main competitors for the most-corrupt title are other havens of machine politics like Louisiana, New Jersey, and Florida.6 And you have to go a long way to be worse than Louisiana, with their rich corruption-gumbo legacy of the infamous Long family. Louisiana’s crooked governors like Edwin Edwards and its racist gubernatorial candidate, the tax cheat David Duke, closely rival Illinois’ convicted governors. Whether or not Illinois is more crooked or has more colorful rogues than our erstwhile rivals, by anyone’s account we are one of the most corrupt states in the nation.

Our title of most corrupt doesn’t only rest with statistics. Here, as they used to say on the TV program Dragnet, are “Just the facts, ma’am.” Of the last nine Illinois governors, four have been convicted of corruption—getting bargain-priced racetrack stock, manipulating savings-and-loan banks, covering up the selling of driver’s licenses to unqualified drivers, shaking down contractors for campaign contributions, and trying to sell a U.S. Senate seat.

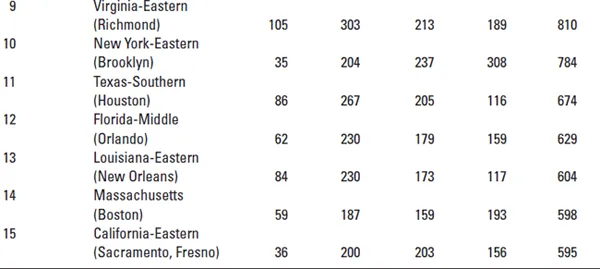

Table 1.1 Federal Public Corruption Convictions by Judicial District 1976–2012

Chicago’s city hall is a famous political-corruption scene as well. Thirty-three Chicago aldermen and former aldermen have been convicted and gone to jail since 1973. Two others died before they could be tried. Since 1928 there have been only fifty aldermen serving in the council at any one time. Fewer than two hundred men and women have served in the Chicago city council since the 1970s, so the federal crime rate in the council chamber is higher than in the most dangerous ghetto in the city. In chapter 4 we detail the aldermanic corruption, and in chapter 5 we cover the rank-and-file corruption of City Hall bureaucrats.

Table 1.2 Federal Public Corruption Convictions Per Capita for Top Thirteen States with the Most Convictions 1976–2012*

In other chapters, we detail many aspects of corruption throughout the state. Altogether, 1,913 individuals were convicted of corruption in federal court between 1976 and 2012; of those, 1,597 convictions were in the greater Chicago metropolitan region. But there is plenty of corruption spread throughout the state at all levels, from small suburban town halls and county criminal courts to the halls of the legislature and state government in Springfield. We do not have a few “rotten apples”; we have a rotten-apple barrel and a pervasive culture of corruption.

In our studies, we often refer to officials convicted of corruption. But for each of them, there are many other public officials who did the same thing but didn’t get caught or didn’t go to trial in federal court. There are only three U.S. Attorneys in Illinois, and they have to focus on all federal crimes, not just political corruption. State’s attorneys and attorneys general for the most part don’t prosecute corruption. Therefore, much of it goes undetected. Inspectors general at the state, county, and city levels have shown conclusively in their reports that corruption in government is more pervasive than just the cases of those convicted would indicate.

Corruption is committed not only by those who break the law. Conflicts of interest are rampant even when they aren’t illegal. It may be legal to give your brother-in-law a government job, but it is still a conflict of interest because you are not objectively determining who is the best qualified for that position. It may be legal to be a public official and have government contractors hire your law firm because they want to influence your decision on future government contracts, but it is a direct conflict of interest. These types of conflict of interest—when an official’s economic interest rather than the public interest is served—occur much more frequently than outright crimes.

Nonetheless, the governor’s mansion, Chicago city-council chambers, the state legislature, and quiet suburban city halls house more criminals and have a worse crime rate than most bad neighborhoods or towns. And we have elected and reelected officials in Illinois even after we knew they were corrupt. We reelected Dan Rostenkowski to Congress after his conflicts of interest were well known, and we reelected Rod Blagojevich as governor after the indictment of many of his cronies for corruption schemes.

Theories of Corruption

To understand corruption, its causes and possible cures, we can learn from other studies. Rasma Karklins in her work on corruption in former Soviet countries created a general typology of corruption with three classifications:

1. Everyday interactions between officials and citizens (such as bribery for licenses, permits, zoning changes, and to pass inspections).

2. Interactions within public institutions (such as patronage, nepotism, and favoritism).

3. Influence over political institutions (such as personal fiefdoms, clout, secret power networks, and misuse of power).7

We have all three types of corruption in Illinois, and each reinforces the other. In addition, Karklins found that many people in corrupt societies participate in and accept a low level of corruption because, they say, “everyone else does it” or, as in her book title, “the system made me do it.”

We accept Karklins’s typology of corruption, but we are left with the question of why this corruption is committed. Robert Klitgaard, in his book Controlling Corruption, argues that “[i]llicit behavior flourishes when agents have monopoly power over clients, when agents have great discreti...