![]()

1. The Odyssey of a Nice Girl

Elocution and Women’s Cultural Aspirations

But under all the twisting and halting of her career … she knew that there had been one thing after all—the need to satisfy the craving for something that was deep and beautiful and beyond what people called “everyday things.”

—Ruth Suckow, The Odyssey of a Nice Girl

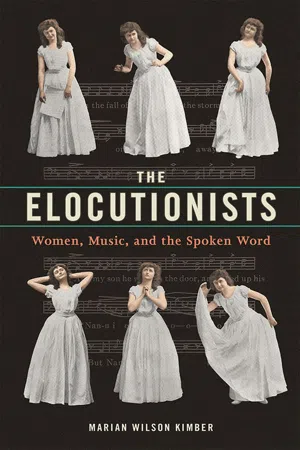

Ruth Suckow’s 1925 novel, The Odyssey of a Nice Girl, which draws on autobiographical details from her own life, centers on a young girl’s search for a meaningful place in the world. Marjorie Schoessel, who both plays the piano and appears as a reciter, leaves her small town to study elocution in Boston. Music, literature, and elocution fulfill Marjorie’s longing for something “real” and provide her with the beauty she craves. Yet the fine arts have a complex and contradictory place in her life—within a limited framework they are appropriate activities for her gender and help to define her as a “nice girl,” but they do not allow her to have a career. Marjorie’s odyssey, notes Karen Neubauer, is limited because of its feminine construction; it is the only “kind of an odyssey a female can have and still maintain the coveted ‘nice girl’ reputation.” Art cannot be successfully integrated into Marjorie’s day-to-day life, and throughout the novel her involvement with elocution creates frustrations that she is never able to overcome. On a larger level, Marjorie’s situation allows modern readers to understand the complicated and sometimes precarious place of performing arts that became associated with women in the Progressive Era. Like Marjorie Schoessel, female elocutionists were striving to find a place for themselves in American cultural life without abandoning socially acceptable gender roles; they ultimately found their efforts rejected and their chosen art form too feminized to be considered culturally valid.

Marjorie engages with higher cultural forms because of her need for something beyond the world of her small Iowa community. Books give her a “queer dreamy feeling,” and elocution and music both create an audible beauty that transcends common life. Marjorie’s first realization of deeper artistic expression comes from struggling with the Chopin nocturne assigned by her piano teacher:

Little parts, little phrases, began to take on a meaning. It was as if she had stood outside … and then a door pushed open, she could see inside, and go in deeper and deeper. … When people played softly or loudly, they didn’t just do it because of the little marks above the measures. They meant it. … When Miss Davison called for her Nocturne, she stumbled over the first bars, then all at once she knew more than she had ever known before, and the playing was easier, a kind of singing.

Elocution also allows Marjorie to approach the fulfillment she feels in music. In practicing her speeches, “there was a deep new excitement in ‘letting herself go.’ … This gave glimpses of satisfaction, too … a new possession of herself, a loosening of the tight bonds of self-consciousness and timidity.”

Elocution and music are linked in Suckow’s novel, as they were in the late nineteenth century, through the musical vocabulary used to describe Marjorie’s performances: both playing the piano and reciting allow Marjorie to have a “singing” voice. As she read poetry, “words, phrases here and there, sang in her mind, brought that mingled longing and satisfaction.” Marjorie’s teachers in music and elocution can both produce the sounds to which she aspires. When Miss Davison plays, the notes stand out, “making a kind of shape in the air above the shining piano … precise and visible, on a kind of shimmering background.” It is a sound that Marjorie recognizes again in Mrs. Courtwick: “There was something different here, something that she had dimly sensed, and wanted … the lines that she read stood out, clear and definite, like the music that Miss Davison had played. … That was why she must stay at the Academy … to find and grasp that beautiful, secret hidden thing for herself.” The sound that Marjorie hopes to be able to replicate is gendered yet powerful. In her own poetic readings, Marjorie likes the “little soprano note, that answered to something which she dimly sensed as her own,” and elocution allows her to experience the “intoxication of power and ease and beauty that she had to know, to reach, again.” At the Academy recital, Marjorie achieves success: “But she had satisfied herself. … She had spoken it—that little clear soprano note—made it her own.” For women, to make art is to make an expressly feminine sound.

However, there is no appropriate place for Marjorie’s newfound voice when she returns home, and she discovers that the distance between the higher art forms she has been taught and her small town’s culture has become wider. Marjorie is now ashamed of her previous recitations. Her mother wants her to perform locally, but Marjorie doesn’t have an entire program prepared because popular lowbrow entertainment is not the literature for personal development she learned at the Academy of Expression; she finds that her professional training is useless. The poetry that thrills her privately—that of Tennyson, Longfellow, Whittier, Phoebe and Alice Cary, Owen Meredith, Jean Ingelow—“were not pieces that would ‘do to give’—like things from [James Whitcomb] Riley. They were a kind of indulgence, filling her at the same time with elation and helpless dissatisfaction, not fitting into her life.” Great poetry, while personally rewarding, does not work in public performance, just as her earlier absorption in Chopin’s nocturne led Marjorie to abandon lesser works, such as the “Pansy Waltz” or “Monastery Chimes,” that her family enjoys. When she complains about a local woman reading “cheap things,” her mother counters that “no one could expect to give nothing but Shakespeare!”

Marjorie is conflicted not just about the content of her repertoire, but also about the act of performance itself. She is especially embarrassed by the flamboyant performance of a local woman, who melodramatically combines text with musical accompaniment:

She could not explain to them—not even to herself—why it was that she used to sit rigid with a dreadful shame when Mrs. Shrader walked slowly to the platform with a mystic step, opened the manuscript on her reading-stand, and read verses from The Rubaiyat with trills and sudden poundings and soft music from the piano. None of it was real—only a word here and there. And it was the very artificiality, all the palaver, that made the ladies smile at one another with a congratulatory air and think that something impressive was being done.

Marjorie recognizes not a successful female performance in the combination of the two art forms that speak to her most, but a failed attempt by women to achieve high culture, and worse, a self-congratulatory inability to recognize pretension. It is not so much that Marjorie’s education has enabled her to transcend this world; it seems that she fears any attempt at performance on her part will simply confirm her place in it. Marjorie eventually abandons elocution and takes an office job. Nonetheless, at the novel’s close she is still longing for that which art has given to her—“that satisfaction that was warmth in the blood, that gave life a glowing centre”—but which she is somehow denied.

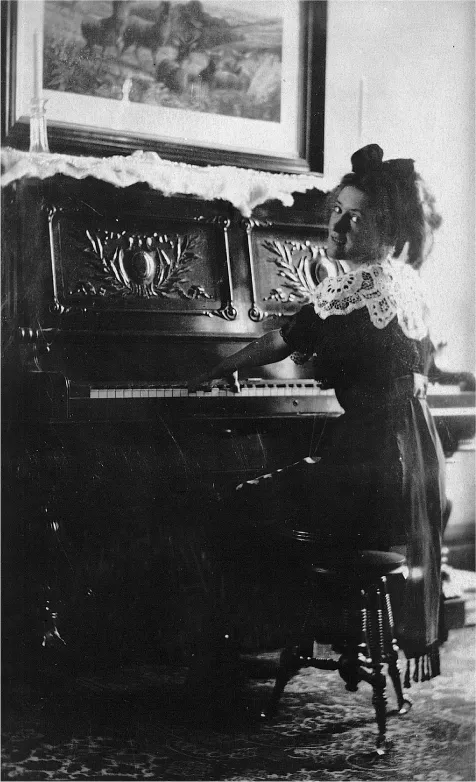

In writing The Odyssey of a Nice Girl, Ruth Suckow drew on her own experiences to create a realistic, if critical, portrayal of the role of elocution in women’s lives. The small-town Iowa native personally understood the motivations behind “nice girls’” engagement with literature and the arts, and the tensions surrounding their ambitions because of their gender. The grandchild of German immigrants, like her fictional counterpart, and the daughter of a Congregationalist minister, Ruth was surrounded by the suppers and entertainments at which young women like Marjorie might perform poetry; at only age seven, Ruth “delivered a nice recitation” at a social event in Algona. Suckow was exposed to the literature and music appropriate for a respectable girl. Her father read selections by Charles Dickens out loud, and her “play characters” were literary and historical figures: King David, Martha Washington, and Tom Sawyer. Early photos of the author reinforce the image of a cultured young lady: at twelve she holds a book, and as a teenager poses at the piano (figure 1.1); one can easily imagine the romanticizing Marjorie in her place.

The world in which Ruth and other middle-class girls grew up was one in which both music and literature, made audible through elocution, represented the highest form of feminine culture. Suckow later described a parlor through a young girl’s eyes; at the center of the domestic sphere were signifiers she “trustingly believed to set a true standard of elegance—a piano with a dumb pedal, a mahogany center table with a Battenburg doily and a mottled-leather copy of Hiawatha.” Despite the gentility of music and literature, women’s cultural aspirations were blocked by societal norms. Thus Suckow could write, in 1926, that although any Iowa town “lets its women folk go in for books and frills in the Woman’s Club,” this world was nonetheless “suspicious of ‘culture’” and the kind of prominent display that elocutionary or musical performance required. Suckow’s recollections of churchwomen emphasized the “cautious fixedness” of their activities: “If musical, they might play the pipe organ, sing or lead the choir—in fact, would be urged, more than urged to do so—they could always teach Sunday School classes, make little talks in the Missionary Society, ‘lead the Devotion.’ But it seemed that I would be better not to go very far intellectually, to keep always within the bounds of churchly convention.”

Suckow apparently found her dramatic activities at Grinnell College insufficient, leaving to enroll in elocutionist Silas Curry’s School of Expression in Boston in 1913. The character of Marjorie was reportedly based on a fellow Curry student, not Suckow herself; nonetheless, much of what Marjorie encounters, including the specific texts that she performed, closely resembles the author’s experiences. Marjorie recites a “child’s piece,” similar to Eugene Field’s “The Doll’s Wooing,” which Ruth performed in 1913; Ruth performed poetry by John Masefield and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, perhaps the inspiration for Marjorie’s lyric gift. Marjorie’s triumph is to play Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream before she graduates; Suckow appeared as a rustic in the play in 1915. Marjorie is offered (but does not take) a job at a conservatory in Mississippi; graduates of the School of Expression taught at three Mississippi colleges. A couple runs the fictional Academy of Expression: Mr. Courtwick, a missionary for his particular pedagogical method, and his intimidating, businesswoman wife. While they were presumably based on Silas and Anna Baright Curry, their name in a manuscript of the novel, “Southwick,” links them to Henry L. Southwick, president of Boston’s Emerson College of Expression from 1908 until 1932, and his wife, Jessie Eldridge Southwick, who taught there. Marjorie’s parents expect her to open an elocution studio; upon Ruth’s return to Iowa, she advertised her availability as a teacher in speech arts, “a Reader, and as a Director of Plays and all forms of Dramatic Art.” But not surprisingly, jobs directing plays in 1915 in Manchester, Iowa, with a population of just under three thousand, were not forthcoming, and the studio was abandoned.

Figure 1.1. Ruth Suckow at the piano. Papers of Ruth Suckow, University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections.

Suckow, like...