![]() Part One Talkin’ ’bout You

Part One Talkin’ ’bout You![]()

Abb Locke Talks about Two-Gun Pete

Blues writer Paul Oliver was, almost from the beginning, the number 1 advocate of listening to the music’s lyrics. Paul maintained that blues lyrics—both prewar and postwar—profiled and reflected the activities of everyday life of African Americans and helped document special events as well as notable individuals in the black community. Chicago’s “Two-Gun Pete” was just such an individual. His real name was Sylvester Washington. He was a notorious black Chicago policeman, reputed to have killed more than a dozen people in the line of duty. Pete had such a fearsome reputation in the black community that legend says he would arrest thugs on the street, and instead of handcuffing and dragging them off to jail he would simply instruct them to report to the station house—and they would! Two-Gun Pete was mentioned several different times on blues records, and from time to time stories of his career or tales of personal runins with Pete were part of the conversation among blues musicians. One of the major Chicago newspapers ran an article on him and Life magazine had published an impressive photo of Pete on duty. I was fascinated to hear that there was such a character on the Chicago scene. After reading the printed articles and hearing the stories I asked around to see if anybody in particular had more stories about Two-Gun Pete. Dick Shurman said the man to talk to was Abb Locke. Abb was a regular on the Chicago blues scene working as a tenor player in the bands of Howling Wolf and Otis Rush. Abb had rented a room in a tavern/boardinghouse owned by Two-Gun Pete and was running-buddies with him for a few years—so all the stories were firsthand.

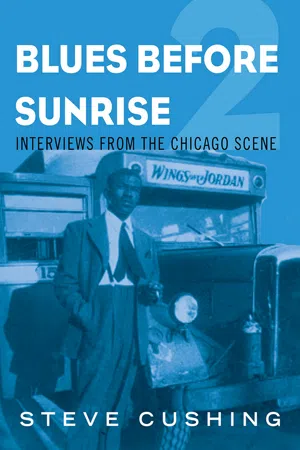

“Two-Gun” Pete. Photo courtesy Scotty Piper Collection, Chicago History Museum.

This interview was recorded May 28, 2013. Abb Lock died in March 2019.

I contacted Abb and we met in the office of Delmark Records in Chicago.

Abb, when did you first meet Two-Gun Pete—what year was it?

About 1958—somewhere in there …

And was he still a cop when you knew him?

No—the last person he killed, the church got him off the force because he was killing too many people. … But he still had power [laughs] because he originally got many of those people at the Police Department jobs. I had to find me a room because I was sleeping with a buddy of mine from Cotton Plant, Arkansas—that’s where I’m from, Cotton Plant, Arkansas—and they went back home and I had to find me a room. Well another friend of mine was still here and he stayed with Two-Gun Pete. He told me I could get a room over there in Pete’s place. Pete had a tavern with rooms for rent upstairs. So he took me over there and I met Two-Gun and I got a room there. Then the very next week that same buddy and Pete got into it; but you don’t really get into it with Pete—you just talk nice and get on away from there [laughs]. So when my buddy left, Pete asked me if I was leaving. I didn’t have nowhere to go—and it was a nice room, I had me a little TV up there and nobody bothered me. You didn’t have to worry about nobody bothering you because nobody came up there. After my buddy left, there wasn’t anyone there except me and Pete. Pete—he’d be drunk everyday—everybody’s scared, too scared to be around there. Pete’s place was right there by the lake—Thirty-Ninth and Lake Park. Some people be going to the lake and the guy stop by to get a beer with his wife, and Pete—by him being drunk and mean, he might call your wife a bitch and then say, “Now tell your husband to defend you!” See, Pete’s ready to shoot him—and the guy’s scared to death. Both the husband and wife are scared to death. Then Pete might go in the backroom and get something and they’d both jump up and run out of there [laughs]. The truth is, I didn’t have nowhere else to go, so whatever he said to me, I said, “You-are-right!” If he cussed me out I said, “You-are-right!”—nothing but “You-are-right!” I’d come downstairs and I’d go into the bar and he’d say “Now, you know you ain’t got no money—whatcha doin’ in here?” And I would say “You-are-right!”—and I left back out. Maybe the next week I’d go in there two or three times and then he got to like me. “Locke, you’re all right!” Well, yeah! And he got crazy about me then. So I wasn’t goin’ nowhere—because I didn’t have nowhere to go. … I was paying $15 a week—well that was a lot of money then. Anyway, he got to like me and I was his buddy then. If I didn’t have my rent money he’d say “Don’t worry about it, Locke! You know you ain’t got to worry about it.” “Yeah—but I got to pay you.” [Laughs.] “Naw, don’t worry ’bout it!” Then, he had me behind the bar—and he’d be over there half-drunk and asleep and he put a pistol down there—I wasn’t gonna mess around with that pistol—I don’t care what happened! He’d be over there asleep and I’d have to watch over him while he slept and make sure nobody came in there and messed with him. And he’d cook everyday—about eleven or twelve o’clock he’d call “Locke!—C’mon down!” And I’d get up and go down there and he’d done cooked—greens and beans and meat. He cooked! And he had a Thunderbird convertible and he took me with him everywhere he went. He’d go downtown to pay his bills, down to the bank there before you get to Woodlawn before you get to Sixty-Third Street—he’d go to the bank and do his banking, you know? Then we’d go downtown, go down and eat and stuff, all in that convertible. He treated me nice—I was his righthand man. He could trust me. “Locke, I like you. You’re all right!” We got along good, he liked me and he wouldn’t let nobody mess with me. I was playing with Howling Wolf, and Wolf came over and parked his truck there, came in and said he was looking for Abb Locke. Pete pulled his gun and put it up against Wolf’s neck and started shouting “What do you want with Abb Locke? What do you want with Abb Locke?” And I walked in and yelled “Wash!”—I didn’t call him Pete—I called him Wash. His real name was Sylvester Washington, and I called him “Wash” for short. I said, “Wash, he came to pick me up. That’s Howling Wolf!” And Pete’s saying, “Oh, oh, oh” with the gun under Wolf’s neck [laughs]! He wasn’t going to let anybody mess with me—“Nobody messes with Abb Locke!” And when we got in the truck Wolf says, “I ain’t never goin’ back in that God-damned joint anymore! You be outside when I come by here!” [Laughs.]

People call him Two-Gun Pete to his face?

NO! You didn’t do that—not to his face. I knew him about three years and I never heard anybody call him that. In fact, I don’t remember anybody calling him Pete. I always called him “Wash.”

How many people did he kill?

I’ve heard everything from seven to seventeen but I think it was actually eleven. Now, you know, he didn’t like policemen. Yeah, he was a policeman—but he didn’t like policemen. A policeman came in there and got smart with him. A white policeman came in and got smart with him in his own joint—and Pete whupped him and dragged him outside, leaned him up against the wall bleeding, right by the door. Pete was kind of rough—you know? He was a brute. He could kill you with his bare hands. I got scared and I said, “I better get out of here. Somebody’s gonna blow this place up.” He looked a lot like Red Foxx, you know, Fred Sanford? Picture Fred Sanford, only a couple inches taller, looked just like him. And Pete kind of walked like that, too—drawers with suspenders and no shirt and both guns on his waist. When he was a policeman, he’d walk down the street and there’d be a lot of thugs on the corner. And he’d tell them all “I want you all off this corner”—he’d say it real low. And when he came back, if they were still on that corner, that gun would come out—and that stick—and he’s whupping heads with that gun on em. I mean whupping heads! [Laughs.] His daughter was on dope. Somebody put her on dope and she came in there crying, and he’d say “Look at this bitch!” and he’d be mad. She came by there crying a lot of times, but he never did find out who put her on dope. And Pete’s wife left him for the coal man. Yeah, she was scared and she just wanted to get out of there—and she left with the coal man. [Laughs.] Pete had a girlfriend, a lady about forty years old. Pete wanted to be a big lover, and they’d go upstairs. He’d come down and say “Locke, I been up there two hours on that woman!” He’d go back in the bar somewhere and his girlfriend would say “Two hours shit! He’s been up there asleep!” [Laughs.] My buddy came up from Memphis. His name was George Coleman. You can hear him blow the alto solo on B. B. King’s record “Woke Up This Morning.” And George didn’t have anywhere to stay, so I got him a room at Pete’s place. Anyway, somehow or other he and Pete got into it, arguing, and Pete was gonna kill him. My room was up on the second floor and I told my buddy, “Stand beneath that window. I’m gonna throw your clothes out that window. You get them clothes and get away from here or that man’s gonna kill you! You got no business arguing with that man” [laughs]. And he got away from there. He’s living in New York city today.

When you hung out with Pete, were you at all concerned about possibly being in the line of fire?

Well, I thought about it—but I didn’t think about it too long because, really, nobody wanted to mess with Pete. But yeah, it might have been dangerous—like you say, in the line of fire [laughs]! He had a buddy who was a policeman from St. Louis. He came and stayed with Pete for about a week on vacation—and he had his two guns on behind the bar. Both of them had their guns on—both had one in the front and the other gun in back, you know, big holsters all around.

Having known Pete for some time, did you have any idea what made him so mean-spirited?

Something was wrong with him. I think he was worried about all those people he killed, that’s why he kept those pistols. He was afraid family or friends of the people he had killed would try to retaliate—take revenge—and he wanted to be ready. So he kept the one gun in the front pocket and one in the back—just to be ready—even when he went to bed at night and got out of his pants, he laid those pants out right by the bed so he’d be ready. All that fear built up. He wouldn’t let anybody know, but I think deep down inside he was afraid.

What finally convinced you to move from there?

I was on the road with the Wolf and we come in from Florida. When you came into Pete’s place, one door—you’d go in the bar; and the next door, located right next to it there—you’d go upstairs. When I came in, I hollered at him, I yelled, “Wash!” He was walking on upstairs and I thought he heard me so I opened that same door going upstairs behind him. When I opened that door behind him, he turned and put that gun dead on me. He said “Locke! You know better—you know to say something!” I said “I hollered at you—I thought you heard me.” But he didn’t hear me. That shook me up. I had to get out of there. I left the next day …

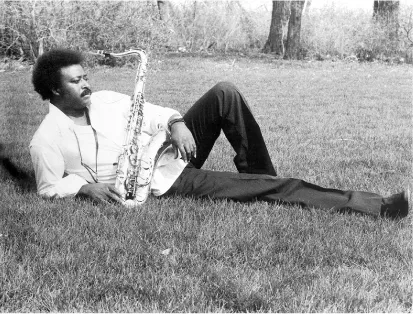

Abb Locke. Photo courtesy The O’Neal Collection.

After you moved out did you ever come back to visit?

I never went back in there but I’d drive by there on my way somewhere else and see him sitting out there. I’d stop and wave at him—and he’d wave back. I might stop and holler at him “How you doing!” He’d always say, “Locke, You’re all right! I wish I could be like you!” After I left, the little girl he was going with, he used to whup her every day. I don’t know why—but he used to whup her every day. And one last day he whupped her, and she stabbed him—and he died …

![]()

Brewer Phillips on Memphis Minnie

One of the real delights of postwar blues is the second-line guitar. The electric bass wasn’t available until around 1958. Before that time, many bands would feature two guitars—one playing the lead, the other playing a complementary second part, usually consisting of rhythmic “lumps,” combined with chording and appropriate finger-picking lines. It was a genuine skill onto itself, a real rarity, and there were a limited number of players on the Chicago blues scene accomplished in this role—Jimmy Rogers, Johnny Young, Lee Jackson, and Brewer Phillips. Brewer worked with Hound Dog Taylor, playing second-line guitar to Taylor’s slide guitar leads. I saw a lot of Hound Dog and, therefore, a lot of Brewer. Brewer was an accomplished second-line guitar in a very rough-and-tumble fashion, a way that was in keeping with his overall image as a person. Brewer cut sort of a menacing figure in a downhome way. He wasn’t evil, slick, and calculating; his threat was a sort of out-of-control personality freshly emerged from the back alleys. He had very few teeth left, and the couple that remained reminded me of pumpkin seeds inserted in available vacancies up front. He had kinky black hair styled in a comb-over that resembled a black sock draped from one side of his head over to the other, with a handful of coins bulging in the toe. Since I mostly saw him on the bandstand, he was always drunk, loud, and profane—usually spouting off about his sexual intentions or about the money he had recently begun to make now that their band was playing out on the road. I worked in Magic Slim’s band playing drums—and Slim and Hound Dog were friends. Whenever Hound Dog and Brewer fell out with some bandstand dispute, Hound Dog would ask Magic Slim to play second guitar in Brewer’s place—which Slim did reasonably well. Also, Slim and his band had taken over the Sunday matinee gig at Florence’s, long hosted by Hound Dog and band, so when Taylor and the guys were back in town, they would visit on Sunday afternoons. Also, during my early days on the blues scene I was sort of a nighttime running buddy with Hound Dog for a while. Apparently, Hound Dog had such a tragic childhood that even as a sixty-year-old man he was still scared of the dark and wouldn’t go to sleep until the sun rose. So he spent weeknights in Chicago visiting the clubs that supported live music, and I spent a series of Tuesday nights out on the town with him. I knew Hound Dog well but only saw Phillip on the bandstand, and what I saw convinced me to keep my distance—until an incident about two years later. During my time with Magic Slim on the Southside, I was the victim of a shooting. I was shot pointblank with a .38 pistol, just barely survived and spent a good deal of time in the hospital recovering—a week in intensive care and another three weeks as a recovering patient. During that time I was visited at the hospital by Hound Dog, which surprised me, but we were friends—and by Brewer Phillips, which amazed me. They showed up together—and it wasn’t just the visit that surprised me, it was an entirely different Phillips than I had previously seen. He was quiet, sober, and beni...