- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

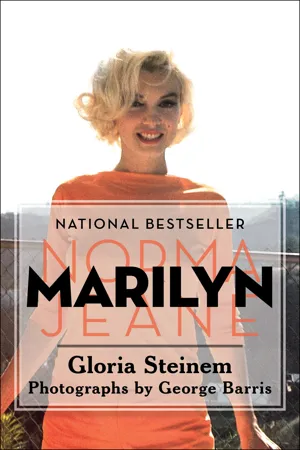

Marilyn: Norma Jeane

About this book

The feminist icon and

New York Times–bestselling author offers an intimate appraisal of the ultimate sex symbol—and the real woman behind the images.

Few books have altered the perception of a celebrity as much as Marilyn. Gloria Steinem, the renowned feminist who inspired the film The Glorias, reveals that behind the familiar sex symbol lay a tortured spirit with powerful charisma, intelligence, and complexity.

This national bestseller delves into a topic many other writers have ignored—that of Norma Jeane, the young girl who grew up with an unstable mother, constant shuffling between foster homes, and abuse. Steinem evocatively recreates that world, connecting it to the fragile adult persona of Marilyn Monroe. Her compelling text draws on a long, private interview Monroe gave to photographer George Barris, part of an intended joint project begun during Monroe's last summer. Steinem's Marilyn also includes Barris's extraordinary portraits of Monroe, taken just weeks before the star's death.

"An even-handed introduction to the Monroe phenomenon." — Library Journal

Few books have altered the perception of a celebrity as much as Marilyn. Gloria Steinem, the renowned feminist who inspired the film The Glorias, reveals that behind the familiar sex symbol lay a tortured spirit with powerful charisma, intelligence, and complexity.

This national bestseller delves into a topic many other writers have ignored—that of Norma Jeane, the young girl who grew up with an unstable mother, constant shuffling between foster homes, and abuse. Steinem evocatively recreates that world, connecting it to the fragile adult persona of Marilyn Monroe. Her compelling text draws on a long, private interview Monroe gave to photographer George Barris, part of an intended joint project begun during Monroe's last summer. Steinem's Marilyn also includes Barris's extraordinary portraits of Monroe, taken just weeks before the star's death.

"An even-handed introduction to the Monroe phenomenon." — Library Journal

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Fathers and Lovers

“I’m just mad about men. If only there was someone special.”—Marilyn Monroe

EVEN WHEN SHE WAS unknown, and certainly after she became an international sex goddess, Marilyn Monroe had the good luck and the bad luck to cross paths with a surprising number of the world’s most powerful men. The fragile framework of her life was almost obscured by the heavy ornaments of their names. For those many people who have been more interested in the famous men than in Marilyn, her story often has become a voyeuristic excuse. Like a gossip column:

Marilyn’s career began when she was discovered by an Army photographer assigned “to take morale-building shots of pretty girls” in a defense plant for Yank and Star and Stripes magazines and Marilyn was a pretty eighteen-year-old worker on the assembly line. That photographer’s commanding officer, a young captain who spent World War II supervising this kind of morale-building work from his desk in a movie studio, was Ronald Reagan.More pinup shots of Marilyn were published in magazines like Laff and Titter, and they caught the attention of Howard Hughes, the actress-collecting head of RKO Studios, as he lay in a hospital recovering from a flying accident. A gossip column report that he had “instructed an aide to sign her for pictures” encouraged a rival studio, Twentieth Century-Fox, to sign her as a starlet. It probably also led to a date between Hughes and Marilyn, from which she emerged with her face rubbed raw by his beard, and the gift of a pin that, she was surprised to learn later, was worth only five hundred dollars.Marilyn was paid fifty dollars for the nude calendar shots she did under another name, but just one was bought for five hundred dollars once she was an actress and had been identified as the model. The purchaser was an unknown young editor named Hugh Hefner, and that nude greatly increased the appeal of the first issue of Playboy. (A year after her death, nude photos taken on the set during her swimming scene in Something’s Got to Give, her last and unfinished film, would increase Playboy’s sales again.) An original copy of that historic nude calendar also hung in the home of J. Edgar Hoover. Though he accumulated an FBI file on Marilyn, Hoover, whose only known companion for forty years was a male aide, proudly displayed this nude calendar to guests. Originals of that calendar continue to sell for up to two hundred dollars each. For years, a well-known pornographic movie called Apple Knockers and the Coke Bottle was also sold on the premise that Marilyn was the actress in it—but she was not.Of the two most popular male idols of the 1950s, Joe DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra, she married one and had an affair with the other. Of the two most respected actors, Marlon Brando and Laurence Olivier, she had an affair and long-term friendship with the first and costarred with and was directed by the second. She played opposite such stars as Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, Tony Curtis, and Jack Lemmon, and was directed by some illustrious directors: John Huston, Joe Mankiewicz, Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, and Joshua Logan. She costarred and fell in love with Europe’s most popular singing star, Yves Montand. She married one of the most respected American playwrights, Arthur Miller, and acted in a film he wrote for her.When Prince Rainier of Monaco was looking for a wife to carry on the royal line, Aristotle Onassis thought Monaco’s fading tourism might be boosted if the new princess were also glamorous and famous. He asked George Schlee, longtime consort of Greta Garbo, for suggestions. Schlee asked Gardner Cowles, scion of the publishing family and publisher of Look magazine, who came up with the name of Marilyn Monroe. Cowles actually hosted a dinner where Marilyn, newly divorced from Joe DiMaggio, and Schlee were guests, and Marilyn said she would be happy to meet the Prince (“Prince Reindeer,” as she jokingly called him). But plans for “Princess Marilyn” were cut short when Prince Rainier announced his engagement to Grace Kelly. Marilyn phoned Grace with friendly congratulations: “I’m so glad you’ve found a way out of this business.”The CIA may have considered using an acquaintance between Marilyn and President Sukarno of Indonesia for foreign-policy purposes. In 1956, at Sukarno’s request, she had been invited to a diplomatic dinner during his visit to California. He was clearly taken with her. There were rumors that they saw each other afterward, though Sukarno, who liked to brag about his sexual conquests, didn’t brag about Marilyn. Later, when a coup against his regime in Indonesia seemed imminent, Marilyn tried unsuccessfully to persuade poet Norman Rosten and Arthur Miller, by then her husband, to “rescue” Sukarno by offering him a personal invitation of refuge here. “We’re letting a sweet man go down the drain,” she protested, with characteristic loyalty to anyone in trouble. “Some country this is.” In 1958, according to a CIA officer in Asia, there was a plan to bring Marilyn and Sukarno together in order to make him more favorable to the United States, but the plan was never fulfilled.At the 1959 American National Exhibition in Moscow, a close-up of Marilyn in Some Like It Hot was shown on sixteen giant movie screens simultaneously, and applauded by forty thousand Soviet viewers each day. When Premier Nikita Khrushchev made his famous visit here later that year and Marilyn was one of the stars invited to a large Hollywood luncheon for him, he seemed to seek her out. Other introductions waited while he held Marilyn’s hand and told her, “You’re a very lovely young lady.” She answered: “My husband, Arthur Miller, sends you his greetings. There should be more of this kind of thing. It would help both our countries understand each other.” Though Marilyn refused to disclose this exchange, it was overheard and published. As she was boarding the plane to New York, the reporters applauded her, as if thanking her for thawing the Cold War a little. Marilyn was very touched by that. “Khrushchev looked at me,” she later said proudly, “like a man looks at a woman.”As part of her quest for education, Marilyn sought out writers and intellectuals: Truman Capote and Carl Sandburg were among her acquaintances. (She was “a beautiful child” to Capote. Sandburg said: “She was not the usual movie idol. There was something democratic about her. She was the type who would join in and wash up the supper dishes even if you didn’t ask her.”) As part of their quest for popularity, writers and intellectuals sought out Marilyn. Drew Pearson, the most powerful of Washington columnists, got her to write a guest column in the summer of 1954. Edward R. Murrow chose her for one of his coveted televised “Person to Person” interviews. Lee Strasberg, serious, Stanislavsky-trained guru of the Actors Studio, took her on as a pupil, ranked her talent with that of Marlon Brando, and seemed impressed by her fame. (“The greatest tragedy was that people, even my father in a way, took advantage of her,” said his son, John Strasberg. “They glommed onto her special sort of life, her special characteristics, when what she needed was love.”)Another writer and intellectual who wanted to meet Marilyn was Norman Mailer. “One of the frustrations of his life,” Mailer explained, characteristically referring to himself in the third person in Marilyn, the biography of her he wrote a decade after her death, “was that he had never met her… The secret ambition, after all, had been to steal Marilyn; in all his vanity he thought no one was so well-suited to bring out the best in her as himself…” In this lengthy “psychohistory” of Marilyn, he finds significance in the fact that her name was an (imperfect) anagram of his, and describes her as “a lover of books who did not read… a giant and an emotional pygmy… a sexual oven whose fire may rarely have been lit…” What he does not say is that Marilyn did not want, to meet him. Although—or perhaps because—she had read his work, she refused several of Mailer’s efforts to set up a meeting, “formal or otherwise,” through their mutual friend, Norman Rosten. “She resisted his approach,” wrote Rosten. “She was ‘busy,’ or she ‘had nothing to say,’ or ‘he’s too tough.’” Under Rosten’s continuing pressure, she finally issued Mailer an invitation to a party—at a time when he couldn’t come—but nothing more private. Though Mailer quotes from Rosten’s slender book about Marilyn, he omits the account of his own rejection.Marilyn was flattered by attention from serious men, but she also had standards. “Some of those bastards in Hollywood wanted me to drop Arthur, said it would ruin my career,” she explained after her public support and private financial aid with legal fees had helped Arthur Miller survive investigation by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. “They’re born cowards and want you to be like them. One reason I want to see Kennedy win is that Nixon’s associated with that whole scene.” While in Mexico, where she went in the last months of her life to buy furnishings for her new home in Los Angeles, she met Fred Vanderbilt Field, a member of the wealthy Vanderbilt family and known as “America’s foremost silver-spoon Communist,” who was living there in exile. He and his wife found her “warm, attractive, bright, and witty; curious about things, people, and ideas—also incredibly complicated… She told us of her strong feelings about civil rights, for black equality, as well as her admiration for what was being done in China, her anger at red-baiting and McCarthyism, and her hatred of J. Edgar Hoover.”As an actress, she often objected to playing a “dumb blonde,” which she feared would also be her fate in real life, but she might have accepted the “serious actress” appeal of playing Cecily, a patient of Sigmund Freud. After all, the director of this movie was John Huston and the screenwriter was Jean-Paul Sartre, who considered Marilyn “one of the greatest actresses alive.” Ironically, Dr. Ralph Greenson, a well-known Freudian who was Marilyn’s analyst in the last months of her life, advised against it, because, he said, Freud’s daughter did not approve of the film. Otherwise, Marilyn would have been called upon to enact the psychotic fate she feared most in real life, and to play the patient of a man whose belief in female passivity may have been part of the reason she was helped so little by psychiatry.The paths of these men in Marilyn’s life also crossed in odd ways. Robert Mitchum, Marilyn’s costar in River of No Return, had worked next to her first husband, Jim Dougherty, at an aircraft factory, and heard him discuss his wife, Norma Jeane. Elia Kazan, with whom Marilyn once had an affair, later directed After the Fall, Arthur Miller’s play that was based on his marriage to Marilyn. At a post-play party, Kazan and Miller could be heard comparing intimate notes on Marilyn while being served supper by Barbara Loden, the young actress who played the part of Marilyn and to whom Kazan was later married.Most famous of all these famous men was Jack Kennedy, with whom Marilyn was linked both before and during his presidency, and Bobby Kennedy, with whom she was linked while he was attorney general. In the absence of the rare and unwonted witness to an affair, the evidence to most private romances is hearsay or one-sided. But Marilyn told many friends of both affairs, and was seen at parties, arriving and leaving hotels, on the beach at Malibu with Jack, and at the home of Kennedy brother-in-law Peter Law-ford with Bobby. The unanswered questions about her death, books and televisions shows on possible conspiracies, right-wing and left-wing motives for her “murder”—these have assured that Marilyn’s name will be linked with the Kennedys for all the years she is remembered. Partly because of them, there seems to be more interest in her death than in her life.

Marilyn appealed to these men who were friends and strangers, husbands and lovers, colleagues and teachers, for many different reasons: some wanted to sexually conquer her, others to sexually protect her. Some hoped to absorb her wisdom, while others were amused by her innocence; many basked in the glory of her public image, but others dreamed of keeping her at home. “She is the most womanly woman I can imagine,” Arthur Miller said before their marriage. “… Most men become more of what they are around her: a phony becomes more phony, a confused man becomes more confused, a retiring man more retiring. She’s kind of a lodestone that draws out of the male animal his essential qualities.”

Norman Mailer’s opinion was even more sweeping. She “was every man’s love affair with America,” he explained in Marilyn. “… The men who knew the most about love would covet her, and the classical pimples of the adolescent working his first gas pump would also pump for her… Marilyn suggested sex might be difficult and dangerous with others, but ice cream with her.” She was a magical, misty screen on which every fantasy could be projected without discipline or penalty, because no clear image was already there.

What Marilyn and the real Norma Jeane inside her wanted from men was much more limited and clear, but almost as magical, as what they expected from her. She hoped to learn, not to teach; to gain seriousness not sacrifice it; to trust completely but not to be completely trustworthy; to be protected “inside” while a man took on the world “outside”; to be younger, never older; to be the child and not the parent. In short, she looked to men for the fathering—and perhaps the mothering—that she had never had. She didn’t want the mutual support of a partnership, but the unconditional, one-sided support given to a child.

Jim Dougherty was very aware of his role. When Norma Jeane was told about her illegitimacy before their marriage, she determined to get in touch with her real father—the handsome, idealized man she had known only as a photograph.

“This is Norma Jeane,” Jim remembered her saying in a tremulous voice when she finally got the courage to phone the fantasy stranger she had dreamed of all her childhood. “I’m Gladys’s daughter.”

“Then she slumped and put the receiver back,” Dougherty wrote in his memoir of their marriage. “‘Oh, honey!’ she said. ‘He hung up on me!’

“After that incident,” he explained, “I’d say we were closer than ever. I was her lover, husband, and father, the whole tamale. And when my leave had just about run out and I was getting ready to return to the ship, it was another very emotional experience for her… Each time I left it was a destructive thing that hit her extremely hard. She wanted something, someone that she could hold onto all the time. If we were out together, even at the movies, she had a tight grip on my arm or my hand.”

Throughout their marriage, Marilyn called her young husband “Daddy.” Jim’s trips with the merchant marine were not just the sad absences of a partner, but traumatic desertions by a parent. Without those long trips the marriage might have lasted for the reason that many once did: the wife had neither the financial nor the emotional ability to leave. But once she felt deserted, Norma Jeane turned to work in the defense plant where she was to be “discovered”; to brief affairs with other men for warmth and security, and to modeling and acting as a way of living in her fantasies for a few minutes or hours at a time. She felt emotionally separated long before the divorce papers were signed.

When Marilyn fell in love for what she described as the first time, the man was even more clearly a father figure. Freddy Karger was a musician employed by movie studios to do vocal coaching (he was Marilyn’s teacher); a divorced man raising his son (he was not only older but literally a father); a dark, handsome, compact man (like the man in the photograph); and a part of an unusually close household that included his mother, his divorced sister, his sister’s two children, and his own son, all of whom took Marilyn into their hearts (a ready-made family). Indeed, there was the added seduction of the Karger family’s home as a kind of Hollywood salon where anyone from Valentino to Jack Pickford had gathered. It contrasted painfully with Marilyn’s life as a starlet eating on as little as a dollar a day and living in a lonely furnished room. When Karger first brought Marilyn home to dinner, he said to his mother, “This is a little girl who is very lonely and broke.” Marilyn felt taken care of. She fell in love.

Unfortunately, Karger seemed to feel only some combination of sexual attraction and pity for Marilyn—not love. He was almost as rejecting as her absent father had been. She was no masochist in her relationships with men—if anything, she exacted an impossible degree of loyalty and support—but in her obsession for first love and first family combined, she accepted almost anything.

“I knew he liked me and was happy to be with me,” Marilyn wrote, “but his love didn’t seem anything like mine. He criticized my mind. He kept pointing out how little I knew and how unaware of life I was. It was sort of true. I tried to know more by reading books. I had a new friend, Natasha Lytess. She was an acting coach and a woman of deep culture. She told me what to read. I read Tolstoy and Turgenev. They excited me, and I couldn’t lay a book down till I’d finished it… But I didn’t feel my mind was improving.”

“‘You cry too easily,’ he’d say. ‘That’s because your mind isn’t developed. Compared to your breasts it’s embryonic.’ I couldn’t contradict him because I had to look up that word in a dictionary. ‘Your mind is inert,’ he’d say. ‘You never think about life. You just float through it on that pair of water wings you wear.’”

But the final insult came when Karger said he couldn’t marry her because, should anything happen to him, his son would be left with her. “It wouldn’t be right for him to be brought up by a woman like you,” Marilyn remembered Karger saying. Given the child inside herself and her special kinship with children, that was the ultimate cruelty.

“A man can’t love a woman for whom he feels contempt,” Marilyn explained. “He can’t love her if his mind is ashamed of her.” She tried to leave Freddy Karger but couldn’t stay away. (“It’s hard to do something that hurts your heart,” Marilyn wrote movingly, “especially when it’s a new heart and you think that one hurt may kill it.”) When she finally left for good, Karger, at least in Marilyn’s memory, suddenly became more interested—but it was too late. “I was torn myself and wondered, Could it work?” Karger later said. “Her ambition bothered me to a great extent. I wanted a woman who was a homebody. She might have thrown it all over for the right man.”

She did remain friends for the rest of her life with Freddy’s mother, Anne Karger, just as she later would remain close to Joe DiMaggio’s son, to Arthur Miller’s children and his father, Isadore Miller, long after she was divorced from those two husbands. One of the consistencies of her life was this habit of attaching herself to other people’s families: to Natasha Lytess and her daughter; to Lee and Paula Strasberg and their two children; to poet Norman Rosten, his wife, Hedda, and their daughter; to photographer Milton Greene and his wife, Amy; to Dr. Ralph Greenson, his wife and two children, who took her in as part of her treatment—to every friendly home that crossed her path. The life-style and relatives that came with a particular man seemed to attract her more, and to survive longer, than the man himself.

Freddy Karger added another association to the gossip value of Marilyn’s life. In spite of his professed desire for “a homebody,” he soon married Jane Wyman, newly divorced from Ronald Reagan and the mother of Maureen and Mike Reagan. Karger and Wyman divorced, remarried, and divorced again. While they were married, Marilyn wrote about Karger without naming him, saying only, “He’s married now to a movie star… and I wish him well and anybody he loves well.”

But having learned a painful lesson of unequal love, Marilyn’s next serious affair was a more paternal one. Johnny Hyde, an important agent thirty years her senior, felt much more for Marilyn than she did for him. It was Hyde who helped her get the small but crucial role in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, who praised her talents to every important producer in Hollywood, and who made sure she was seen at all the right parties.

To Hyde, she confessed the truth of her emotional numbness after Karger, and he listened to her with kindness and understanding. “Kindness is the strangest thing to find in a lover—or in anybody,” she wrote about Hyde. “No man had ever looked on me with such kindness. He not only knew me, he knew Norma Jean...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- About This Book

- The Woman Who Will Not Die

- Norma Jeane

- Work and Money, Sex and Politics

- Among Women

- Fathers and Lovers

- The Body Prison

- Who Would She Be Now?

- Image Gallery

- Technical Data

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Marilyn: Norma Jeane by Gloria Steinem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.