This is a test

- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

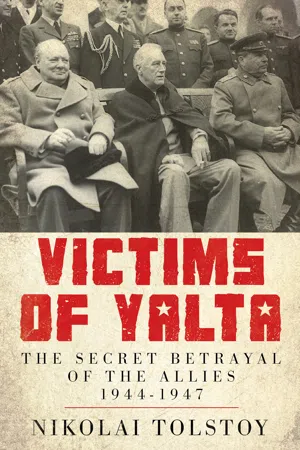

A “harrowing” true story of World War II—the forced repatriation of two million Russian POWs to certain doom ( The Times, London). At the end of the Second World War, a secret Moscow agreement that was confirmed at the 1945 Yalta Conference ordered the forcible repatriation of millions of Soviet citizens that had fallen into German hands, including prisoners of war, refugees, and forced laborers. For many, the order was a death sentence, as citizens returned to find themselves executed or placed back in forced-labor camps. Tolstoy condemns the complicity of the British, who “ardently followed” the repatriation orders.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Victims of Yalta by Nikolai Tolstoy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

RUSSIANS IN THE THIRD REICH

On the morning of Sunday, 22 June 1941, Shalva Yashvili* had planned to enjoy an extra hour in bed. A young Red Army lieutenant in the army occupying Soviet Poland, and by his own account a shy and rather gentle young man, he had three months of his two-year service to go. After that he would return to the sunny mountains of his native Georgia. It seemed unlikely at this late stage that anything would occur to impede his return to civilian life, though it is true that senior instructors visiting his artillery regiment had of late devoted time to teaching recognition of German tanks, field artillery and other items of the Wehrmacht’s weaponry. This seemed odd, as relations between the Third Reich and the Soviet Union appeared as cordial as they had been since the two greatest powers of the Eurasian land mass had joined in dividing Poland between them.

The day before, Yashvili had been relieved of the boredom of mounting guard at the regimental ammunition dump, and had set off with a friend for the nearby town of Lida, in Byelorussia just across the border, on the traditional Saturday night’s search for entertainment. After seeing a film they returned to the great barracks, solidly built in the days of Tsar Nicholas II, and stayed up late chatting. The friend, who came from Buryat-Mongolia, was fascinated by Yashvili’s descriptions of the rugged, smiling land of Georgia, so different from the bleak and windy tundra of his own remote province. He particularly loved the luscious oranges Yashvili received in parcels from home, and could hardly be brought to believe that there existed a land where such apples of the Hesperides could be plucked freely by any wayfarer.

But neither young man was to enjoy a late lie-in. To his disgust a half-awakened Yashvili was aroused abruptly by the wholly unexpected sound of the barracks alarm. It was six in the morning, and barely light. Trying to collect his thoughts, he rushed out, pulling on his uniform as he went. But even as he and his comrades emerged, bleary-eyed and disgruntled, they were met by an officer going round to say that it was a false alarm and all could go back to sleep.

Grumbling at their superiors’ insensitivity, the soldiers tumbled back into bed. This time their slumbers lasted an even shorter time. Within two hours a distant thud of explosions shook the barracks windows, and the alarm rang out again. The artillerymen dressed hastily and piled out into the town square. There they found a huge crowd of officers and soldiers of units gathered from all parts of the town, shouting excitedly and asking questions.

Yashvili heard a number heatedly explaining that, ten minutes before, aeroplanes had bombed and machine-gunned certain quarters of the town. Several houses had been destroyed, and some people had apparently been killed. Others declared that there could not have been an attack; it must have been manoeuvres. Yashvili soon decided that something more than manoeuvres was happening, particularly when it appeared that the mysterious raiders had discharged a number of bombs on to the town railway station, destroying quantities of guns, tanks, ammunition and petrol stacked on sidings and by the tracks. Still, no orders came and only confusion reigned. The crowd of soldiers milled about, and it was not until ten o’clock that anyone felt impelled to start issuing instructions.

The different units had assembled and moved to open country encircling the town. Yashvili and his company stood waiting and wondering, when up came an officer to enquire whether anyone present knew how to fire a four-barrelled anti-aircraft gun. Yashvili stepped forward. He was at once ordered to take his company, with four such guns, to protect a neighbouring aerodrome from the possibility of attack by paratroopers. He was given a three-ton truck for transport and, at about six o’clock in the evening, set off on a laborious journey to the aerodrome.

Yashvili had himself as yet seen no signs of war, if war it was. But during the midday wait he learned that he had unwittingly been close to death. The ammunition dump which he had only just been relieved from guarding was sited some five miles out of town. In the half-light of early dawn dive-bombers had come spinning out of the sky, hurling down bombs which had sent the whole dump up in one blinding explosion, and killed all twenty-two of the guard company. ‘Operation Barbarossa’, the German invasion of Russia, had begun.

Yashvili’s truck was now driving through the night, with no headlights permitted and for the most part in first gear. Two or three times they ended up in a ditch, and it was after dawn next morning when they reported to the aerodrome. There a major directed them to take up a defensive position in woods on the outskirts. Yashvili and his fellows (there were twenty-four of them, including the driver) accordingly moved off, positioned their guns, and settled down to wait.

As the day drew on and nothing occurred to disturb the tranquillity of the fields and forests in which their post nestled, the soldiers unbuttoned their military shirts and relaxed. Not far off was a building, which Yashvili and some of his comrades went over to investigate. It turned out to be the kitchen for a nearby prison camp, and a Polish girl asked if the men would like some food. They followed her to a great storehouse. It was locked, but the girl proved able to open it, and when the soldiers entered (a little gingerly), they found themselves in a veritable Abanazer’s cave of comestibles; the place was stocked to the ceiling with giant hams, strings of sausages, sides of bacon, and crates of vodka. The soldiers’ mouths watered, but knowledge of penalties exacted in the Soviet Union from those who laid hands on state property held them in check.

The girl reassured them, and from her and a bewildered prisoner who returned from a week-end’s leave they learned the situation. The inmates of the prison-camp were driven out each day to perform forced labour on the aerodrome.1 As soon as news of the German invasion was confirmed, the whole population, guards and captives, vanished. None knew where they had gone, but at any rate they were unlikely to reappear soon. As for the riches of the storehouse, these were the supplies kept for the mess-room of the NKVD guards. As became the foremost guardians of the Revolution, they did not stint themselves. The delighted soldiers spent the next hour cramming their truck and stomachs with good things. That evening they did not trouble to send to the aerodrome for their rations.

It had been an uneventful and leisurely day, but as night came on matters resumed their former unpredictable course. The major’s orderly who should have done the rounds of the outposts failed to appear. After waiting some time, Yashvili sent a messenger to the lieutenant commanding their neighbouring company. The soldier returned, scratching his head, and reported that there was nobody there. The young officer then despatched his messenger to the major in charge. Back came the envoy: the major and everyone else had vanished too! All had melted away, leaving the lone twenty-four with their lorry.

There was nothing for it but to try to rejoin the regiment. They piled into the truck and returned to the town. All was confusion, with the streets and square packed with retreating troops. Making their way through the throng, the lost company drove first to Regimental Headquarters. Once again they drew a blank: the building was a blackened and empty shell, having received a direct hit from German bombs. Faced with this final check, the young Georgian decided he had no alternative but to join the fleeing throng pressing eastwards back to Russia.

With no plans beyond this, Yashvili and his men drove out of the town as evening was coming on, and billeted themselves on a grumbling Polish farmer. A sentry was posted by the main road to keep an eye out for units of their regiment. The men were settling down, when the sentry ran in to say that he had just stopped one of their captains on the road. Yashvili came out, and was told by the captain that his battery had been moved nearer the front to protect a road. In the meantime they were to follow him and rejoin the rest of the regiment.

They drove all that night, reaching the regimental camp in a wood next day. There they learned that Yashvili’s battery officer had been killed and the entire battery destroyed. This news did not by now seem very shocking or surprising, as it was evident that chaos reigned throughout their section of the front.

At midday, Yashvili was ordered to join the regimental ammunition convoy. This consisted of sixty trucks, under the command of a captain. They were given a map-reading as their destination, but no further explanation or alternative orders. Still, at least they were part of the integrated structure of the army once again.

Bumping along the forest road, they continued for several miles until the braking of the foremost truck brought the column to a halt. Yashvili, about twentieth along the line, leaned out and saw that his captain was being harangued by two senior officers. One wore on his collar the red and black tabs of a general from the Headquarters Staff, whilst the other was a field general. After some discussion the convoy captain jumped out of his truck and got into the next one. The two generals took his place in the leading lorry and the procession trundled on, to come to a halt shortly afterwards.

The captain told the men they could have a short rest period, and then came over to Yashvili. It appeared that he had received a ferocious lambasting from the generals for being so foolish as to drive by daylight. ‘Are you mad, dourak (blockhead), to drive by daylight? Don’t you realise what will happen if the Stukas catch you in the open? Learn a little sense, if you can, and from now on keep under the trees by day and drive only by night!’

Not daring to excuse himself by quoting his previous orders, the poor subaltern jumped to obey. When darkness fell, the two martinet generals once again sat in the leading truck and directed the pace of the journey. It proved an unnerving experience for the drivers, as they were not allowed to use their headlights. In addition, the leading vehicles moved in a most erratic way, constantly stopping unexpectedly—presumably through fear of hidden obstacles. All each lorry-driver saw was the sudden flashing of the brake lights of the truck in front. During the entire night they moved by recurring stops and starts a few miles only. And, needless to say, a number of accidents took place. Russian military trucks had their radiators situated right at the front of the bonnet, so that a relatively mild collision with the rear of the preceding truck resulted almost invariably in a burst radiator and a useless lorry. The vehicles so damaged had to be nosed aside into the ditch. Of sixty trucks which had set out the night before, only twelve were still intact next morning.

However, the generals made no comment, and explained to the captain that they were now only a dozen miles from an ammunition dump. They gave him documents empowering him to collect as many shells as they were able to take back to the regiment. The generals then departed, leaving strict instructions that once again the convoy was to wait for darkness before moving off.

When night came the captain took the remains of his convoy slowly and carefully along the allotted route. Despite the shortness of the journey, it was not until morning that they reached their destination. When they did, they found that the entire ammunition store was no more. It too had been blown to pieces by an aerial attack.

The reality of their situation began to dawn on the two young officers. The two ‘generals’ were in fact German agents who had succeeded in depriving a Red Army artillery regiment of vital ammunition for some three days, destroying forty-eight lorries in the process. If they were achieving elsewhere even a tithe of this success, these enterprising agents alone must be spreading chaos in Soviet ranks.2

Two factors had greatly assisted the impostors. One was the fact that, as Yashvili stresses, ‘in the Red Army no one questions an order; he just obeys’. The other was that the disguised generals spoke perfect Russian and had perfected the hectoring manner which Red Army soldiers expected from their generals. Ironically, the disguised Russian generals were almost certainly Russians, and quite possibly generals in reality as well! For the Counter-Intelligence Department of the Wehrmacht, the Abwehr, had set up special commando units for operation behind the Soviet lines. Recruited from White Russians and Russian-speaking Balts, Poles and Ukrainians, and given impeccably tailored Soviet uniforms, they were able to achieve successes far beyond the ordinary in this type of warfare.3

The two young officers returned with their twelve trucks (the ninety-six lorryless drivers and mates came as passengers) to the regiment. When their colonel learned that he had not only not got the expected shells, but had also lost four-fifths of his precious trucks in this foolish way, he was beside himself with rage. Still, there was nothing to be done, and as German units launched an attack shortly afterwards, the ammunition-less artillery regiment was obliged to continue its retreat. Continually attacked from the air when on the highroads, they were obliged to move slowly through the woods. There the ground was too soft to take the heavy 122 mm guns, and an order came to abandon them. The demoralised remnant of the regiment was regrouped with other units to form a somewhat ragged division of survivors. News had come that the Germans had already reached Minsk, far to the east, and so the retreat continued through the forests.

It was at this time that Lieutenant Yashvili underwent his first and brief experience of actual fighting. Sent out on patrol, he came round a bush to find himself face-to-face with a German. Both fired off a round and bolted for cover, neither having been hit. But after this slightly ludicrous incident, events took a more serious turn, and the Georgian was hit by a bullet which passed through both legs. He was treated by an attractive young woman doctor (he can still recall his acute embarrassment when she told him to take down his trousers: he was, after all, not yet twenty-one). He was then taken to the battalion casualty section, where he found a corner of a lorry in which to rest.

But there was no rest for the Red Army in the summer of 1941. The Germans began to press home another attack, and bullets came whipping through the sides of the parked lorries. Ignoring his wounds, Yashvili flung himself from the lorry and dragged himself along the ground to the safety of some bushes. But this spurt of energy proved too much for his weakened frame, and he fainted. Debilitated from pain and loss of blood, he slept all that day (2 July) where he lay. When he finally woke, the sun was already setting behind the birch trees. He raised himself up, and found he was lying in the midst of an archipelago of mortar-bomb craters. They had been crashing and splintering all around the spot on which he lay: he is understandably convinced that the hand of God was upon him that day.

Everywhere was quiet; even the leaves of the trees had stopped rustling. Yashvili picked himself up gingerly, and staggered off—whither, he was not very certain. He had no gun, no knapsack, and no idea where to find his or any other unit of the Red Army. That morning he had been one amongst fifty thousand armed men; he was now unarmed and alone, except for the corpses. The only living creatures there besides him were some army horses from the artillery train. With extreme difficulty, he crawled to one and managed to scramble into the saddle. Despite the serious nature of his wounds, the young lieutenant felt little pain, and his main concern now was to find somewhere he could receive medical attention.

His first act was to remove his military tunic and stuff it into a saddle-bag. There was now nothing to single him out as a soldier; his fear was that, with daylight failing, he might be shot by either side as he emerged from the trees. An hour’s ride brought him to the edge of the forest, and there, about three miles off, he could see a village. As he approached, he became aware from the distant hum and twinkling lights that a great crowd was assembled. Drawing nearer, he came on two bedraggled officers sitting on their horses beyond the perimeter of the houses. They shouted to Yashvili to join them, suggesting they could help each other. They also asked him if he was prepared to go amongst the milling horde of undisciplined soldiers occupying the village, and beg some food. They explained that, as officers, they were afraid of being shot by the men if they went amongst them. A great many officers had been killed by their men during the first weeks of war. As there was now nothing about Yashvili’s appearance to suggest his being an officer, he agreed.

He rode in amongst the cheerful, drunken mob to where a group was cutting up a cow they had just killed, and asked for a piece. A burly soldier with a knife looked up and, seeing the stained trousers and blood-filled boots of the rider, hurled across with rough good humour the throat and lungs of the slaughtered beast. The hideous slippery object nearly knocked Yashvili from his horse, but he clutched hold firmly and rode back in triumph with the prey to his waiting comrades. They were delighted, and all three rode off furtively. They boiled portions of this unappetising joint in their helmets by a woodland stream...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CONTENTS

- CHRONOLOGY

- Preface to Corgi edition

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: Russians in the Third Reich

- 2: Russian Prisoners in British Captivity: The Controversy Opens

- 3: The ‘Tolstoy’ Conference: Eden in Moscow

- 4: British and American Agreement at Yalta

- 5: The Allied Forces Act: The Foreign Office versus The Law

- 6: From Paradise to Purgatory

- 7: The Cossacks and the Conference

- 8: From Lienz to the Lubianka: The Cossack Officers Return Home

- 9: The End of the Cossack Nation

- 10: The Fifteenth Cossack Cavalry Corps

- 11: Interlude: An Unsolved Mystery

- 12: The End of General Vlasov

- 13: Mass Repatriations in Italy, Germany and Norway

- 14: The Soldiers Resist

- 15: The Final Operations

- 16: National Contrasts: Repatriation Pressures in France, Sweden and Liechtenstein

- 17: Soviet Moves and Motives

- 18: Legal Factors and Reasons of State

- APPENDIX

- EPILOGUE

- NOTES

- INDEX

- Copyright Page