CHAPTER 1

From Curse to Crusade

Milton Wexler was a Hollywood psychoanalyst who counted a number of movie stars among his friends and patients. His two daughters, Alice and Nancy, were all that any father could ask for: bright, attractive, and full of promise. In 1968, Alice, the older of the two women, was twenty-five and deep into graduate studies in Latin American history at Indiana University. Twenty-two-year-old Nancy, who would play a key role in the coming genetics revolution, was following her father’s profession. She held a bachelor’s degree from Harvard’s Radcliffe College, had studied briefly under Sigmund Freud’s daughter, Anna, in England, and had just returned from Jamaica, where, under a Fulbright scholarship, she had spent the academic year studying the mental health problems of the poor. That fall she would begin her doctoral studies in psychology at the University of Michigan.

The two women had come to Los Angeles to celebrate their father’s sixtieth birthday. But Wexler had asked them to his apartment to talk of their fifty-three-year-old mother and his ex-wife, Leonore. As the girls sat on his bed, the shades drawn against the fierce California summer sun, Wexler described recent events in Leonore’s life. A calm and rational man who had spent a career choosing his words carefully, he struggled to control his emotions.

A few months before, Leonore had to report for jury duty, he told them. She had gotten up early, dressed carefully and impeccably as was her habit, and driven downtown, putting her car in the parking lot near the courthouse. As she was crossing the street, she was approached by a policeman. “Aren’t you ashamed of drinking so early in the morning?” he admonished her. Only after her anger at such rudeness subsided a few moments later did she realize that she had been walking erratically, weaving in a manner that suggested drunkenness. Alarmed, she called her ex-husband, who, trying to keep her calm, suggested she continue on to court and then come over to his office.

This much, while distressing, wasn’t totally surprising to Nancy and Alice. When they were young, Leonore had been an attentive, loving mother, but she also suffered bouts of moodiness, depression, and erratic behavior. “I remember my mother was a lousy driver,” Nancy recalls. “Once when I was a teenager, sitting in the car with her going down Sunset Boulevard, she kept driving in this sort of herky-jerky way, pulling and pushing her foot on the gas pedal, as if she was some sort of Sunday driver who didn’t know what she was doing. I lost my temper and yelled at her. It was cruel thing for a kid to do, but, of course, back then, I didn’t know. She was so upset she stopped the car and told me to get out, which was a very unusual thing for her to do.”

Such behavior seemed to afflict Leonore more frequently as the years passed. While Nancy was in Jamaica, Leonore had come to visit her. “I was shocked by the change in her,” Nancy says. “We slept together in the same bed. Before we fell asleep, as we talked, her arms and legs seemed unusually restless; I’d never seen that before.” Moreover, “she had become so infantile she couldn’t go off on her own. She couldn’t shop. She seemed so absolutely lost inside herself.”

Shortly after Leonore called her ex-husband in a near panic, Wexler called a colleague, a neurologist, who hurried over to the psychoanalyst’s office as soon as Leonore arrived. After listening to Leonore’s story and the history of her symptoms, his diagnosis was quick and certain.

Leonore had Huntington’s disease.

“It shocked me,” Milton Wexler says. “All I felt was horror. All I could think about was my two beautiful daughters, both working on their doctorates, and I got sick.”

That afternoon in the bedroom Wexler told his daughters of the neurologist’s verdict. Huntington’s disease was incurable and untreatable. It would slowly but relentlessly destroy their mother’s mind, steal control of her body, and, eventually, take away her life.

Then Wexler had to broach the matter that had sickened him so. Huntington’s disease is a genetic disease. Leonore had apparently inherited the Huntington’s disease gene from her father and there was a fifty-fifty chance she had unwittingly passed it along to each of her daughters. And, what’s more, there was no way to know if they had inherited it.

“Imagine what it must be like telling your grown children something like that,” Nancy says two decades later. “Alice and I immediately decided we would never have children, that we’d never knowingly take the risk our parents unknowingly had taken. We said it boldly to Dad, as if that at least was something we could do. Dad said that if he had known, he wouldn’t have taken the gamble of having us, but that he wasn’t sorry that we were here. We were stunned, too stunned to cry, and, I think, mostly worried about our mother and each other.” Then, with a brashness of youth and, most certainly, in an effort to reassure their father, the young women declared, one after the other, “Well, fifty-fifty isn’t so bad.”

Among the three thousand or so known human genetic diseases, Huntington’s has its own peculiar tragedy. It is a genetic time bomb. The inheritance of the Huntington’s disease gene is implacably fixed at the moment of conception, but the symptoms of the disease don’t become manifest until the carrier approaches or reaches middle age, usually years after he or she has borne children. Thus, the defect is preserved and unwittingly passed on through the generations. It is a rare disease, with about 25,000 American victims afflicted at any one time, and another 125,000 who, like Nancy and Alice Wexler, are at risk of having the gene and who may yet develop the disease.

“It is the most terrifying disease on the face of the Earth,” says Milton Wexler, “because its victim is doomed to absolute dementia as terrible as Alzheimer’s disease, a loss of physical control akin to muscular dystrophy, and a wasting of the body as bad as the very worst of cancers.”

The disease is named after George Huntington, a mid-nineteenth-century physician who practiced medicine on the eastern tip of Long Island. In 1872, in the only scientific paper he ever published, titled “On Chorea,” Huntington described a scene he encountered while driving along the road from Amagansett to East Hampton, the area that today is the playland of the well-to-do and the literati but was farmland at the time. “We suddenly came upon two women, mother and daughter, both tall, thin, almost cadaverous, both bowing, twisting, grimacing,” he wrote.1 At the time, such uncontrolled movement was diagnosed as an adult form of Saint Vitus’ dance. But Huntington was aware that the frenetic movement and staggering gait of the two women was far different from the Saint Vitus’ dance seen in children who temporarily developed uncontrolled movements during a fever (now known to be a temporary result of bacterial infections).

As a child, Huntington often had accompanied his grandfather and later his father, both physicians who had practiced in the same area, as they made their rounds. He had seen similar patients then and knew that the disease progressed “gradually but surely, increasing by degrees and often occupying years in its development until the hapless sufferer is but a quivering wreck of his former self.”2

Then, in an observation that was to enshrine his name permanently in the literature of medicine, he noted that the strange chorea (the medical term for purposeless movements) appeared to run in families, “an heirloom from generations away back in the dim past.” He observed that, when either parent had the disease, “one or more offspring almost invariably suffer from it, if they live to adult age. But if these children go through life without it, the thread is broken and the grandchildren and great-grandchildren are free from the disease.”3

In 1968, almost a century later, little else had been learned about Huntington’s disease. It was known that the inheritance of the mysterious gene from parent to child followed the pattern of what the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel called a dominant gene (or “hereditary factor,” in Mendel’s words) in pea plant experiments. It was later shown that, as with Mendel’s peas, human traits are controlled by two factors, or genes, one coming from the father and one coming from the mother. In his plants, Mendel showed that in some cases an inherited trait will be expressed because of the presence of a single dominant gene from just one of the parents, while in other cases two recessive genes, one from each parent, are required for a trait to be expressed. (If brown eyes is a trait in humans that is dominant, only one brown-eyed gene is needed from one parent for the trait to be expressed, whereas blue eyes require the inheritance of two recessive genes, one from each parent.)4

Beyond this slender fact, Huntington’s disease remained an enigma. The purpose and functioning of the defective dominant gene and its normal counterpart was a complete mystery. Try as they might, scientists could find no biochemical abnormality in the blood, urine, or tissues of Huntington’s disease victims that even hinted at how the gene carried out its lethal work. The anatomical and biochemical abnormalities seen in the brain at autopsy gave no clues. And there wasn’t any way to find where the gene resided on the twenty-three pairs of human chromosomes. Without even one of these discriminating factors, there was no test that could tell Nancy or Alice whether they had inherited their mother’s deadly, defective copy of the unknown gene, in which case they, too, would develop the disease in mid-life—or whether they had inherited her normal copy, in which case, in Huntington’s words, the thread was broken.

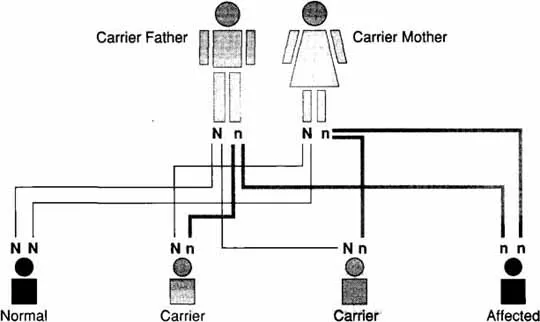

How Recessive Inheritance Works

Both parents usually unaffected, carry a normal gene (N) which is generally sufficient for normal function despite the presence of its faulty counterparts (n)

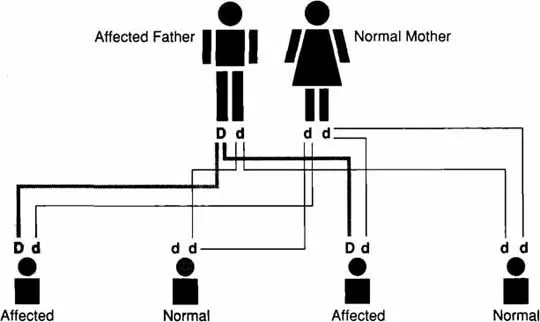

How Dominant Inheritance Works

One affected parent has a single faulty gene (D) which dominates its normal counterpart (d)

While Leonore was still lucid, Nancy and Alice questioned her about her family background, hoping, in part, that piecing together the genesis of the disease might somehow lift the veil of uncertainty over their own future. Gradually, it emerged that Leonore’s father, a Russian Jew who changed the family name to Sabin from Maziowieski when he passed through Ellis Island, had come to America at the turn of the century, while still an adolescent. The family had always assumed he left to escape the persecution and poverty that oppressed the Jews in Eastern Europe. But Wexler now strongly suspects her grandfather’s immigration was a conscious or unconscious attempt to escape the tragic malady that afflicted the Maziowieski clan.

Leonore was the youngest of Sabin’s four children and his only daughter. By the time Leonore was born, Sabin must have been showing signs of mental and physical instability, since, in 1921 (when his daughter was only six years old), he was institutionalized in a state hospital on Long Island. Seven years later he died.

By the time Milton Wexler and Leonore Sabin met, however, her father’s fate was a submerged family secret. Leonore was a bright, vivacious young woman who loved to dance. She had studied for a master’s degree in biology at Columbia University and, when they met, she was teaching high school in the Bronx. Milton Wexler was tall and dapper, stylish in dress and manner. He already had a thriving law practice on Wall Street and, for the times, was doing quite well. (Soon afterward, Wexler abandoned his practice and followed some friends into what he felt would be the more exciting field of Freudian psychology, eventually receiving a doctoral degree from Columbia University.)

Wexler later told his daughters that, on several occasions, while he was courting Leonore in Brooklyn, Leonore’s mother and brothers took him aside as though they wanted to divulge some private family matter, but they seemed unable to specify exactly what it was.

In 1950, when the Wexlers were living in Topeka, where Wexler researched schizophrenia at the famous Menninger Clinic, word came that Leonore’s eldest brother, Jessie, forty-eight years old, was “having trouble” and had to quit work. The three Sabin “boys” had been delightful uncles, Nancy recalls. In their youth they had been fun-loving, and, fascinated with “swing” and jazz, all played musical instruments. When they were older, Paul and Seymour formed the Paul Sabin Orchestra and played at the Tavern on the Green and the Hotel Delmonico in New York City, and at posh hotels in Miami. Jessie fancied himself an amateur magician and delighted his nieces with fabulous tricks, spinning coins around his fingers at top speed and making them magically appear out of his ears, his nose, and his pockets.

Nancy and Alice remember, however, that on their occasional trips to Brooklyn from Topeka, their uncle Jessie began to seem “odd.” He spoke with a slur and shuffled when he walked. “I remember on one visit, he seemed to be having trouble with his magic, the tricks didn’t work, the coins fell to the floor while his fingers danced and twisted,” Nancy notes.5

Jessie soon sought a neurologist who, after examining him, asked to see the other two Sabin brothers. All three, he concluded, suffered a “progressive degeneration of the brain . . . of unknown etiology . . . with poor prognosis.” Huntington’s chorea wasn’t mentioned at first, and the family outwardly behaved as if the strange disorder was a coincidental occurrence instead of what it was, a frightful trick played on all three brothers at birth.

In fact, while the news surprised Milton, it almost demolished Leonore. Growing up, Leonore had somehow come to believe that her father’s disease, which she knew to be Huntington’s, only affected males. But when Jessie’s illness was finally described as Huntington’s, a neighbor of the Wexlers’ in Topeka, a neurologist, told them that men and women were equally at risk. Leonore suddenly realized that not only were her brothers likely to experience the worst that was possible from the family curse, but that she and her young daughters also were at risk. Neither Milton nor Leonore discussed this possibility, burying it as if that could make it go away. Nonetheless, Nancy believed that from then on her mother’s “equanimity about herself and her children’s genetic safety was smashed.”6

Realizing he would soon have the burden of supporting his brothers-in-law, Wexler abandoned his beloved research at the Menninger and moved to Los Angeles to open a private practice in psychoanalysis. One by one, the Sabin brothers died of the disease. Milton and Leonore continued to keep the nature of the curse in the shadows, never telling Nancy and Alice. “I had known there was something the matter in my mother’s family, something that had hit all her brothers, but I didn’t know what it was,” Nancy says. “My mother was always so hidden about it, it was very hush-hush.”

Milton Wexler does recall briefly reading about Huntington’s disease during this period, but he convinced himself that his wife and children had escaped the disease, since Leonore showed no signs of being affected. “As a rational man steeped in science, it’s almost unbelievable to me now that I could have ignored the possibility,” he says. “But denial is common with the disease. It’s a way to survive.” Wexler later viewed Leonore’s erratic moods and deepening depression over the years as the consequence of mental conflicts traceable to the death of her father in her formative childhood years, compounded by the early deaths of her brothers and the sudden fatal heart attack her mother suffered soon after the Sabin brothers died.

For Leonore, “things began unraveling,” Nancy recalls, “but they were so subtle, so insidious, no one knew what was going on. As I grew older it became clear that something was wrong. She snuggled my sister and me like we were toys or pets, at some elemental level unaware of who we were or what we were about. She listened but often did not respond and did not know how to make it better. She cuddled and kissed and fussed but she also grew softer, sadder, silent, more listless, vague and undefined. It was as if some dark subterranean river was taking her away from us.

“In retrospect, I do not know if the ominous gene was beginning to take hold or if she was mainly numbed and in shock,” Nancy says.7

As Leonore drifted, Milton’s career blossomed. His life was filled with famous people and stimulating research. He began to write screenplays. Coming home at night was “deadly,” he recalls, and in 1964, the Wexlers separated and then divorced. “I was convinced beyond doubt that, if there was any danger, she had escaped it by then,” says Wexler.

But, on that hot afternoon in 1968 when Milton revealed Leonore had Huntington’s disease, the family was forced finally to face facts. Nancy and Alice grieved for their mother, for themselves, and for the children they vowed they would never have. And they began to experience the spectre that hangs perpetually over the children of Huntington’s disease victims. A few days after that devastating session with her father, Nancy was at a friend’s house helping in the kitchen. She dropped a carton of eggs, splattering them over the floor. There was a sudden silence in the room. “No one said a word but I know everyone was thinking what I was thinking: ‘Is this the beginning? Do I have it, too?’ I started watching and worrying, and to this day, any moment of forgetfulness or physical slip can get me going,” she says. Alice agrees: “There isn’t a day I don’t think about it.”

Wexler, however, was not one to passively accept his daughters’ uncertain fate. That August afternoon, “before we could even focus on what it meant, he was telling us, ‘Let’s fight this thing,’...