- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

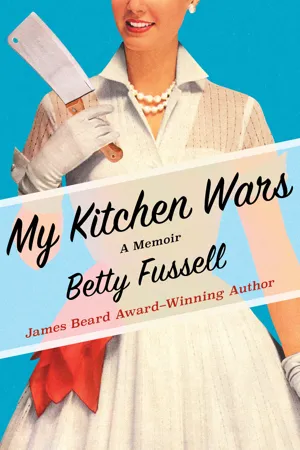

A fierce and funny memoir of kitchen and bedroom from James Beard Award winner Betty Fussell

A survivor of the domestic revolutions that turned American television sets from Leave It to Beaver to The Mary Tyler Moore Show to Julia Child's The French Chef, food historian and journalist Betty Fussell has spotlighted the changes in American culture through food over the last half century in nearly a dozen books.

In this witty and candid autobiographical mock epic, Fussell survives a motherless household during the Great Depression, gets married to the well-known writer and war historian Paul Fussell after World War II, goes through a divorce, and finally escapes to New York City in her mid-fifties, batterie de cuisine intact.

My Kitchen Wars is a revelation of the author's lifelong love affair with food—cooking it, eating it, and sharing it—no matter where or with whom she finds herself. From Princeton to Heidelberg and from London to Provence, Fussell ladles out food, sex, and travel with her wooden spoon, welcoming all who come to the table.

A survivor of the domestic revolutions that turned American television sets from Leave It to Beaver to The Mary Tyler Moore Show to Julia Child's The French Chef, food historian and journalist Betty Fussell has spotlighted the changes in American culture through food over the last half century in nearly a dozen books.

In this witty and candid autobiographical mock epic, Fussell survives a motherless household during the Great Depression, gets married to the well-known writer and war historian Paul Fussell after World War II, goes through a divorce, and finally escapes to New York City in her mid-fifties, batterie de cuisine intact.

My Kitchen Wars is a revelation of the author's lifelong love affair with food—cooking it, eating it, and sharing it—no matter where or with whom she finds herself. From Princeton to Heidelberg and from London to Provence, Fussell ladles out food, sex, and travel with her wooden spoon, welcoming all who come to the table.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Open Road MediaYear

2015eBook ISBN

9781453218433Subtopic

Social Science BiographiesHot Grills

It began innocently enough, with family picnics, the way Camembert begins with a meadow full of cows. But that was a few years and hundreds of hot dogs later, long after Paul and I bought our first house, a cottage paneled in knotty pine and hidden among blue spruce on Queenston Place, just off Nassau Street in Princeton. It was a dollhouse that wouldn’t have taken five minutes to burn to a cinder, and as long as I lived there I feared fire.

We picnickers were mostly young academics in our thirties, from Princeton and Rutgers, some with young children, some without, all of us frolicsome. R. P. Blackmur was our rubicund Lord of the Revels, our Bacchus, with vine leaves in his white hair. The respectables of the Princeton English Department scorned him as a mere writer, a poet-critic with no scholarly credentials at all. And of course they scorned anyone from Rutgers, a state university. But we saw ourselves as outsiders because we cared about Art, in contrast to the philistine Establishment.

Most of the men in our group had been in the service at least briefly, and we all recognized combat as the dividing line between innocence and knowledge, deferring to our vets as we deferred to our sages. For we took combat as the norm, and within the sure Place of the Establishment we fought a guerrilla war as subversives.

Picnics in the wild were rebellion against the white-glove tea parties given by graying deans and their mousy wives. We were bursting with youth, ambition, and libido, and they were not. Picnics were also a rebellion against the four-walled kitchen lives of us faculty wives, bored with changing diapers, fixing school lunches, arranging cocktail parties, typing our husbands’ manuscripts, shuttling our kiddies to ice hockey or ballet. A picnic got you out of the house, away from the eternal routine of setting the table, washing pots and pans, and making and unmaking the marital bed, which, once it had served its procreative function, left little time for play.

And we were desperate to play. We had cleaning ladies and babysitters, but none of us had live-in help. Even if we could have afforded it, a servant by any name would have violated the do-it-yourself code that was a battle cry for us who led kitchen lives. We had discovered, by God, that you didn’t have to buy cotton batting in the supermarket, you could make bread from scratch at home. By God, you didn’t have to pay a dollar a jar for a smidgeon of baby food, you could make applesauce from scratch in your blender. By God, you didn’t have to break your budget by eating in a fancy restaurant where the waiters sneered, you could create in your own kitchen a three-star, five-course meal and have money left over for wine. Of course it would take you two weeks of hard work to do it, but as your husband might unkindly remind you, what else did you have to do?

Curiously, our picnics were not a rebellion against kitchen work. The woman who cooked indoors cooked outdoors as well. I don’t know if blue-collar men were grilling hot dogs and hamburgers in their backyards in the early sixties, but I do know that white-collar academics were not, any more than they were going bowling, hunting, or to the Elks. It was women who toted the bags of charcoal and loaded up the Weber grills and squirted kerosene and watched the flames explode and then subside and the gray ash grow while they manipulated six pounds of ground chuck into thick patties and laid out giant wooden bowls of chopped iceberg lettuce and tomatoes and grated red cabbage slathered with blue cheese dressing and shooed the kids away from the grill as they chased fireflies and each other, while the men stood around and drank. Heavily.

Princeton was an outpost of Cheever territory, where you could drink your way across town from party to party in one long moveable feast. While the women tended the grill, the men tended the thermoses of iced martinis and wrestled with the corkscrews that opened the wine and dispensed the brandy and cigars that finished off the meal. Drinking was men’s work, and the men went at it manfully. The women drank too, of course, and not just to keep up with the men. Drinking was vital to our picnics, loosening tongues and lips and hearts and kidneys. Men could turn their backs and pee openly in the bushes. Women had to choose their coverts more carefully. But the unspoken rule was that you could do things on a picnic that you couldn’t or wouldn’t do in a parlor. Such license was sanctified by a host of pastoral forms, literary and cinematic: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Smiles of a Summer Night, Women in Love, Daphnis and Chloë, Roman de la Rose, As You Like It, Les Règles du Jeu. Food and wine on a greensward or under a grape arbor or even in a backyard were by nature a provocation to lust. Or at least to serious flirtation.

These days we drank, when the cocktail thermos was drained, iced Chablis or an inexpensive Médoc in stemmed glasses. The men had begun to drop the names of wines as easily as the names of obscure Metaphysical Poets, but no matter what the quality of the vintage, the results were the same. Prescriptions for hangovers were as lengthy as the drinking that had caused them. The only thing that interrupted hangover talk was being hangover horny.

Actually, being horny was the reason for our picnics, drink merely the excuse. We had learned during wartime, first the hot and then the cold one, to seize the day. If the Jerries didn’t get you, the atom bomb would. Today was it, and we wanted to gather all the rosebuds we could find, now. The night after we moved to Princeton, Paul and I hired a babysitter and drove to our first dinner party in nearby Kingston. The party was still booming at 1 a.m. when our sitter’s mother called, reminding us quite firmly that we’d promised to be back by midnight. Rather than break up the party, we simply shifted it to our house, and at three in the morning we were swinging in the children’s swings in the backyard and building castles in their sandbox and making far too much noise.

Sex was in the air and on our lips and in the pressure of our bodies when we kissed each other hello and goodbye, a social custom that had infiltrated America’s upper bourgeoisie in the fifties and lingered on, putting a full-mouthed American twist on the Continental habit of kissing both cheeks in greeting. Women rubbed cheeks so as not to leave lipstick behind, but women and men rubbed bodies together like Boy Scouts starting a fire, and the prolonged good-night kiss that began as ritual courtesy might end as rendezvous. Or not. It was an era good for kissing and flirting without anything happening at all.

Except, of course, it did. It had to, the way the Cold War eventually had to hot up after the prolonged foreplay of threats and counterthreats, simulated and real. With Ike and Khrushchev flashing their missiles, Russia was bound to fire off a Sputnik and a Lunik just as we were bound to counter with a Jupiter and an Apollo. Nationally we believed we were in control of our fears, just as privately we believed we were in control of our lusts. Self-delusion clotted the air like sex, and it took but a small charge to blow it sky-high.

Our Princeton pals had already been primed by a quartet of Brits, writers and their wives, who’d revived the days just after the war when a crew of bacchants had danced across the quad—John Berryman, Delmore Schwartz, Randall Jarrell, Allen Tate, Robert Lowell. But the Eisenhower years had lulled the Establishment into a false sense of security, so when Lucky Jim arrived at Princeton in the person of Kingsley Amis, few were prepared. Kingsley cut a swath a mile wide through the faculty wives, literally laying them low with his charm, celebrity, curly blond hair, and bad-boy antics. He’d propositioned me once in the bathroom of our house in Piscataway while I washed out baby Sam’s diaper. “Not quite my idea of a romantic setting,” I said. “Oh,” he said, as if surprised, “would you prefer a bed?”

The Amises had inspired a whole year of husband- and wife-swapping in Princeton before we moved there, and I didn’t know whether to be sorry I’d missed it or glad. There was no scandal left in who had slept with Kingsley. Who hadn’t? The Amises were so very English, and yet not at all like the English revered by the English Department and mocked for all time by Lucky Jim. I tried to imagine resisting Kingsley’s irresistible combination of comedy and sex, as he single-mindedly put one in the service of the other, and I longed to be put to the test. Laughter is the most powerful seduction of all, and for these English, America, with her straitlaced Puritans, was one big laugh-in. They would as soon fuck as say the word; they seemed to have no verbal or sexual inhibitions at all.

In Princeton the Amises lived out scenes Kingsley had already written in Lucky Jim. They accidentally burned a bed-sheet in their rented house and tried to cover it up by cutting a hole in the sheet; Kingsley went off to Yale to deliver a lecture and forgot his briefcase with his speech inside. They were also living out scenes that would appear shortly in One Fat Englishman, like the infamous barge party on the Delaware River by New Hope, in which drunken revelers who’d been screwing in dark corners of the barge kept falling off the boat and having to be fished out of the water half naked. A lot of the time Kingsley couldn’t remember whom he’d screwed, it meant so little and he drank so much.

Another pair of Brits doubled the charge the Amises had ignited. Al Alvarez was an explosive nonfiction writer and his wife, Ursula, distantly connected to D. H. Lawrence, was a ripe raven-haired beauty who wore her hair long and her bosom full. Men flocked to Ursula the way women flocked to Kingsley, but for sex in the opposite mode. Ursula was pure romanticism à La Belle Dame sans Merci, silent to the point of being sullen. When she placed a white rose in her bosom, you could hear the room heave a sigh. Not much later, she ran off with an Irish poet. The poet’s wife committed suicide and Al later attempted the same, then wrote a book about it. The Alvarezes played out tragedy while the Amises played out comedy in our small university town of Anglophiliacs.

Adultery was in the air like wood smoke, only no one called it adultery. It was called Letting Go, and Letting It All Hang Out, in the jargon of that prefeminist era. Now that Freud and Kinsey and Joyce Brothers had told us that women were as sexual as men, now that Marx and Marcuse and Norman O. Brown had told us that sexual morality was the opiate of the masses, it was a liberated woman’s duty not to go out there and get a job, but to go out there and fuck. We were not at war with men. Men were our heroes, and we wanted to love them all, in the high style of Simone de Beauvoir. French women of a certain class had always had lovers, just as their husbands had. So had the English. Why shouldn’t we?

In food as in sex, America was slipping behind us as Europe beckoned. The moment classes were over, we all hopped boats for Europe, often the same boat so that we could continue partying at sea, wallowing in the three large meals a day, wine included free of charge, plus morning bouillon and afternoon tea, provided by the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique. In France, the simplest casse-croûte, a sandwich jambon, in the lowliest bar was a revelation of sensuality that put our picnic sandwiches to shame. We were like amateur painters discovering Picasso. We couldn’t wait to get home to marinate fat shrimp and grill them in the shell so that everyone could peel his own the way the French did it along the Côte d’Azur.

Food was an index of how far we’d moved into the fleshpots of Dionysus, leaving behind the restraints of Apollo. On our backyard grills we’d long since graduated from hot dogs to elephantine sirloin steaks, crusty outside and rare within, to be quilted in garlic butter and served with roasted corn and potatoes wrapped in foil. Now we advanced to butterflied legs of lamb, marinating them in olive oil scented with herbs from Provence, before we seared them on the grill with thick slices of eggplant. Even the men participated when we spit-roasted a whole lamb for Greek Easter in the American-Greek couple’s backyard. Preparing kokoretsi of spiced innards or creamy moussaka topped with béchamel and thick yogurt required ethnic know-how, but anyone could take turns basting the naked lamb before we sliced off smoking hot gobbets to wash down with carafes of pine-flavored wine.

When we moved indoors, everything had to be French. We women were discovering with excitement how to upgrade our Irish stews into boeuf bourguignonne and boeuf en daube. My old fondness for Depression tongue translated into langue au madère, brains were cervelles au beurre noir, and discarded innards like sweetbreads and tripe were now costly ris de veau and tripes à la mode de Caen. Now we planned our dinner parties like surveyors exploring new land. When a hostess set forth a salmis de faisan, she supplied footnotes on what a salmis was. Presenting a poulet chaud-froid, she held a seminar to explain how each layer of white sauce was chilled before the next; and how the whole was decorated with medallions of chicken and topped with truffle cutouts before it was shellacked with layers of clear aspic. The ritual of presentation required responsive aaaahs.

We were discovering what the French had known forever, that food was like literature and art, and that sex was above all like food. But the subtext was always sex. We wanted to have our cake and eat it too, but we didn’t want Betty Crocker cake mix anymore. We wanted dacquoise and génoise and baba au rhum at the end of a Rabelaisian banquet flowing with still wines and sparkling conversation. Every new food opened up new sexual analogues. To explore the interstices of escargots with the aid of fork and clamp, each shell in its place on the hot metal round, each dark tongue hidden deep within the whorls and only with difficulty teased out and eased into the pool of garlic-laden butter—what could be sexier than that? Foods we had known as American but now cooked French revealed a world of innuendo we had missed in our own language. Asparagus that might have gone limp in a steamer stayed stiff with a quick dip in boiling water. Artichokes that had seemed tedious to unleave took on vulvate meaning when the tops of the leaves were cut off and the pith removed and the center made wet with vinaigrette, so that each leaf brought the mouth a step closer to consuming the heart. The canned peach halves that were a staple of my father’s table didn’t at all resemble the glossy operatic breasts of pêches Melba, cushioned on velvet ice cream and rosied by raspberry coulis.

On one climactic occasion it all came together—food, literature, sex, and art. Paul and I staged a dinner to honor Muriel Spark, who was giving a lecture series at Rutgers she called “L’Amour de Voyage.” She appeared at our little cottage in a chauffeured limo, which impressed us and our neighbors no end. She wore a bright red wig and fake eyelashes that nearly swept her plate and entertained us with bawdy stories while we stoked her with course after course: oeufs en cocotte avec caviar, consommé à la reine, blanquette de veau, haricots verts, riz à l’impératrice. By the end of the evening her wig was askew and so were we, but it was all in the cause of Art.

At Princeton, apart from visiting writers, men and women were even more segregated than at Harvard or Yale, where women had infiltrated the graduate schools at least. But if we were excluded from the classrooms, we were all the more valued for our sex. In this atmosphere, I capitulated at last. From now on, I’d be sexy. I made my own clothes, because that way I could afford expensive fabrics and make a good show. I cut the tops of my dresses lower and made the waists tighter. I put tissue in the bottom half of my bras to push my cleavage up. I could feel men buzz around me like drones to the honey pot, and I liked that feeling.

I discovered that all I had to do was ask intelligent questions, and men of all ages would find me intelligent. I could wrap my arm in the arm of the distinguished Eric Kahler, a fellow émigré and friend of Thomas Mann, and while we strolled across campus feel his pleasure as he discoursed learnedly on the relation between Klimt and Freud in the Vienna Circle. I could feel the drama theorist Francis Fergusson glow when I sat at his feet by the fireplace in his Victorian parlor and asked questions about Sophocles. I was only half aware that I was adding new weaponry to my arsenal, the weaponry of flattery and adoration and argument, not as an intellectual exercise but as a form of sex.

If I couldn’t use logic professionally, I’d use it for fun. With the lights on, I would engage one or another young male instructor in heated argument over the superiority of Whitman to Milton, say—the more outrageous the thesis, the better, because it required more skill to defend. It was a fencing match, the thrust oblique and the parry direct, designed to challenge, provoke, and parry other thrusts when, lights out, we danced close and closer to old recordings of “Sunrise Serenade” and “How High the Moon.” So blatantly sexual was argument to us that the wife of one instructor, a trained nurse, rose from her chair one night and said, “I know I can’t discuss la-de-da poetry or the works of Emerson, but I can do this … and this … and this,” and she executed a couple of bumps and a grind that put my mental gyrations to shame.

Dancing, we made love standing up and swaying slow, the way we had in high school and college, teased by the same urges and the same prohibitions, only now it was not virginity we were protecting but marriage. In effect, these were licensed petting parties and there were subtle, unspoken rules about what was and was not permitted. Sitting on laps was okay, dancing so close you could feel each other’s body parts was okay. Fondling in public was not, nor was disappearing into bedrooms, but disappearing outside into nature was. Once I sat on our picnic table out back, huddled under a blanket with a vet who’d seen a lot of action in both military and marital wars, a man whose heroism I much admired and whose horniness when drunk was commanding. He got drunk compulsively, as we all did, and when I indicated kissing was fine but that was it, he didn’t argue, he simply masturbated while we kissed.

Decades before Bill Clinton’s equivocations, we were looking for a presidential solution to the semantics of sex. One evening after a great deal of brandy in front of the fire, Paul and I traded partners with this same vet and his wife. Paul was delighted when we took off clothes, because the vet’s wife had unusually large breasts. I hated to be naked because mine had diminished to nonpregnancy flatness, and I was ashamed of them. I was not surprised when the vet proved to be less interested in kissing them than in kissing parts further south, at which point his wife came alive and hit him on the head with her shoe to make him stop. Nudity was permitted, kissing below the belly was not.

Still, when I was cast as the courtesan Bellamira in a student production of Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, I didn’t have a clue how to play her. As a noted Elizabethan drama critic said kindly after seeing the performance, “Oh, I see, you’re playing it like Margaret Dumont with the Marx Brothers.” Later, I graduated to a full-fledged stripper as the young Gypsy Rose Lee in Gypsy. Blinded by a spotlight as I descended a long staircase without a rail in stiletto heels while singing “Let Me Entertain You,” I was thorou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Epigraph

- Assault and Battery

- To Arms with Squeezer and Slicer

- Annihilation by Pressure Cooker

- Blitzed by Bottle Caps and Screws

- Invasion of the Waring Blenders

- Ambushed by Rack and Tong

- Hot Grills

- Attack by Whisk and Cuisinart

- To Sea in a Sieve

- Cold Cleavers

- Breaking and Entering with a Wooden Spoon

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access My Kitchen Wars by Betty Fussell in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.