![]()

PART ONE

EMPIRE, LITERATURE AND RURAL ENGLAND

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

NATION AT THE CROSSROADS

‘Thank God the athletes have arrived! Now we can move on from leftie multi-cultural crap. Bring back Red Arrows, Shakespeare and the Stones!’ (Tweet by MP Aiden Burley, Olympics Opening ceremony, July 2012).

It was Friday night on 27 July, 2012. The London sky was overcast and a BBC commentator worried aloud about the prospect of rain. There was tension in the air: Britain was about to be showcased to a worldwide television audience of over 900 million people. As the countdown began to the official opening of the Olympics Ceremony, viewers were reminded that ‘Isles of Wonder’ was choreographed by Danny Boyle, the celebrated director of Trainspotting (1996) and Slumdog Millionaire (2008).1 The choice of Boyle as creative director had been announced two years previously. Back then, news media coverage of the impending spectacle was cautiously optimistic. The Guardian went so far as to express ‘delighted astonishment’ at the choice of Boyle.2 But none of this could quite dispel the air of trepidation: would London’s opening ceremony rival Beijing’s 2008 offering? ‘Isles of Wonder’ came with a high price-tag. At £27M it had consumed twice its original budget, yet at £65M the Chinese had spent considerably more.

As nine o’clock loomed, the BBC’s aerial cameras zoomed in on the Olympic Stadium’s blazing lights. As Big Ben’s amplified chime faded, ‘Isles of Wonder’ began with Journey Along the Thames, a two-minute BBC film directed by Boyle. As the film’s title and length imply, the River Thames is followed at high speed from its source in a Gloucestershire field to the heart of London. This journey is full of references to rural representation, from the English idyll to more radical depictions of the countryside by film-makers that Boyle admired, such as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger whose film, A Canterbury Tale (1944), depicted rural Britain as a place of labour and a place of change (landgirls in the fields), but also a place resistant to change. In its opening frames, Journey Along the Thames follows an improbably blue dragonfly as it flits along the water’s surface. Insofar as the dragonfly evokes hot, bygone summers, it belongs to the symbolic terrain of England’s pastoral idyll. Yet its ultramodern electricblue colouring gives an early indication that the film is concerned with updating established ideas about rural England. The film itself is speededup, a device which indicates the passing of time as though to indicate progress from traditional mind-sets. Below, I examine two scenes from the opening ceremony to understand why some spectators were so provoked by it. Their anger is symptomatic of widespread lack of awareness that England’s coastlines, country houses, moorlands, villages and woodlands have multiple global and colonial connections, which this book explores.

Successive images in Journey along the Thames unfold to the accompaniment of ‘Surf Solar’, by a two-piece, mixed-race pop band called Fuck Buttons. Their soundtrack underlines the film’s concern with diversifying images of rural Britain. Boyle’s letter in the ceremony’s official guide hints at this agenda:

‘This is for everyone’ is the theme of the opening ceremony… We can build Jerusalem. And it will be for everyone.3

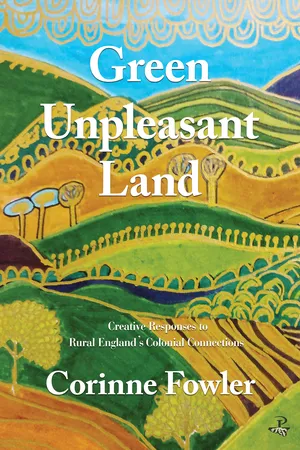

The concept ‘for everyone’ was soon afterwards adopted by the National Trust in its efforts to make the organisation more inclusive. The reference to ‘Jerusalem’ – the song which is commonly considered England’s ‘true national anthem’, based on a poem by William Blake – calls for the creation of a better world, built on ‘England’s green and pleasant land’, a land which – in the context of the opening ceremony – belongs to all, regardless of ethnicity. Yet, as studies of rural racism have consistently shown, rural England is a fiercely guarded site of belonging.4

Early on, Journey to the Thames presents its viewers with two white boys playing in the river with nets and jam-jars. The boys are immersed in a soundscape of birdsong, sloshing water and echoing laughter. It probably refers to a scene in A Canterbury Tale where boys are playing by a river. Two elements of this scene suggest its historical provenance: the receding echoes of laughter and the once-popular pastime of collecting specimens. Its fleeting image is calculated to evoke nostalgia for a lost era of unsupervised play in English meadows. The notion of the rural idyll is evoked by Kenneth Grahame’s riverside classic The Wind in the Willows (1908) when Ratty, Mole and Toad flash on to the screen. The camera passes under a Cotswold bridge before returning to the theme of childhood exploration with a medium close-up of a child brushing his palm against ears of corn. This last image is also given a historical flavour, viewed through a keyhole as though through a doorway to the rural past. These prepare the ground for the film’s concern with dislodging tenacious images of England’s countryside as a white preserve.

The film’s first black face appears as the outskirts of London are reached. A mixed-race woman opens a garden umbrella outside a riverside pub. This is followed by a brief close-up of a smiling Black schoolboy before the camera pans across a field and hovers above an Intercity 125 train. Inside the carriage, an Indian family is seated at a table. The teenage daughter reads the official gold-coloured guide to the opening ceremony.5 A split-second shot of a Black cricketer, a bowler – dressed in traditional cricket whites with a cloth cap and spotted necktie – appears at a culturally sensitive moment, coming straight after shots of the Oxford-Cambridge boat race and the Eton boating song, both of which epitomise elite expressions of Englishness. In this context, the image of an early 20th-century Black bowler is disruptive, not merely reminding supporters that Britain’s colonial masters have frequently been beaten at their own game,6 but because the way he is dressed suggests a historical, rather than recent, Black presence in the countryside. Whether Boyle intended it or not, the image is more complex than it might seem. There was a class tradition where the Marylebone Cricket Club employed professional bowlers as servants to bowl at the gentlemen batsmen,7 and the Caribbean trope of the Black fast bowler and the white batsman persisted at least into the 1930s.8 The only Black cricketers on a 1900 West Indies tour to England were bowlers; all the batsmen were white. But the presence of a Black cricket player is historically appropriate. There was the famous Indian prince, Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji (1872-1933) who played for both Sussex and England between 1895-1904;9 there was Charles Ollivierre (1876-1949) who came with the 1900 West Indian team to England, and thereafter was recruited by the Derbyshire County Cricket club for whom he played between 1901 and 1907;10 and there was Kumar Shri Duleepsinhji (1905-1959), another Indian prince who also played for Sussex and England between 1929 and 1931.11 But almost certainly the film’s reference is to Learie Constantine (1901-1971), a Trinidadian all-rounder who toured England with the West Indies in 1923 and later played in the Lancashire League (perhaps explaining the cloth cap). In Lancashire, Learie Constantine was an immensely popular figure who immersed himself in local radical Labour politics. He later became a formidable influence on racial equality campaigns and legislation. Eventually he became Britain’s first Black peer.12 Yet the Black cricketer might have been seen by the Olympic audience that night as unlikely because this figure challenges collective historical amnesia about Black people’s longstanding and influential association with England’s countryside as well as the nation more generally. In fact, as this book explores, the history of Black and Asian people in Britain before the 1940s was almost as much rural and coastal as it was urban.

That night in July, ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ was the first live spectacle in the stadium. 7,346 square metres of real grass and crops simulated a pastoral, pre-industrial setting. Farmers and milkmaids tended sheep, horses, ducks, goats and geese. The scene featured a cricket match – again including a Black bowler in cricket whites – and four Maypole dances, with a handful of Black children. Actors moved around the white cottages and hedgerows to the accompaniment of choristers singing Parry’s ‘Jerusalem’.

On the surface, the Official Guide commentary on ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ seems relatively innocuous:

This is the countryside we all believe existed once. It’s where children danced around the Maypole and summer was always sunny. This is the Britain of The Wind in the Willows and Winnie the Pooh.13

The statement is actually a gentle reproof which rejects outmoded visions of the past. England’s rural idyll is presented as a nostalgic falsehood (‘the countryside we all believe existed’), a falsehood fed to us by the classic stories we heard as children. This fiction, the commentary implies, has left a rose-tinted imaginative legacy (‘summer was always sunny’). Depictions of idyllic rural childhoods are – the booklet suggests – freighted with nostalgia, a beautiful lie. This lie is undermined by the commentary’s appeal to our contrasting experiences of overcast skies or recurrent summer rain. The use of the singular (‘the Britain’) immediately implies that there are multiple ‘Britains’ with which its citizens variously identify.

From a historical perspective, Boyle did well to place Black Britons in the pre-industrial countryside, since he offered an alternative lens through which to view the nation’s rural past. Yet, in Boyle’s presentation (although the Black cricketer probably recalls Constantine), the presence of Black maypole dancers, farmers and milkmaid...