- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Car Ownership Forecasting

About this book

Originally published in 1982, this book gives a concise commentary on the development and performance of car ownership prediction procedures and a wide-ranging survey of the modelling techniques associated with forecasting. The book provides a basic appreciation of the key points, whether they are mathematical or otherwise. Throughout the book there is a theme which relates the academic debate surrounding the issue to technical rather than philosophical concepts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Modelling in the UK 1900-1960

Despite an increasing research emphasis on traffic prediction during the past twenty years, it would be incorrect to assume that the issue was totally ignored during earlier periods. Although the amount of published material is small there is evidence that British Governments and other bodies have at least been aware of the existence of a growing private vehicle population for most of the present century. It was, however, not until the 1920’s (in the aftermath of the First World War) that the growing number and use of private vehicles required noteworthy changes in highway infrastructure and a need to indulge in some limited prediction of increase in numbers with subsequent “planning” proposals and strategy.

Plowden (1971) has provided a limited summary of the official central government philosophy and policy adopted during the interwar period. Surprisingly, there do appear to have been some limited scientifically-reasoned forecasting procedures along similar lines to those later adopted in the new conditions of the 1960’s. In addition, the inter-war period provoked just the degree of temporal and geographical variations in economic circumstance to test some of the broader assumptions concerning the influence of income on car ownership. As might be expected, the immediate post-war growth in new registrations had declined after 1925 before reviving again from 1931 onwards. Despite severe economic depression in certain regions expansion in the south, coupled with considerable real reductions in car and petrol (running) prices, was sufficient to maintain an increasing growth rate.

Without any apparently rigorous statistical analysis, Plowden reached the conclusion that a major reason for the continuing demand for cars was the steady reduction in cost of purchase and operation. With the growing use of production line techniques, the cost of new cars fell by more than 50 per cent between 1920 and 1928. Prices in 1938 were 33 per cent less than they had been ten years earlier. In line with new prices, running costs also fell. The combined cost of purchase and use fell more than any other item of household expenditure.

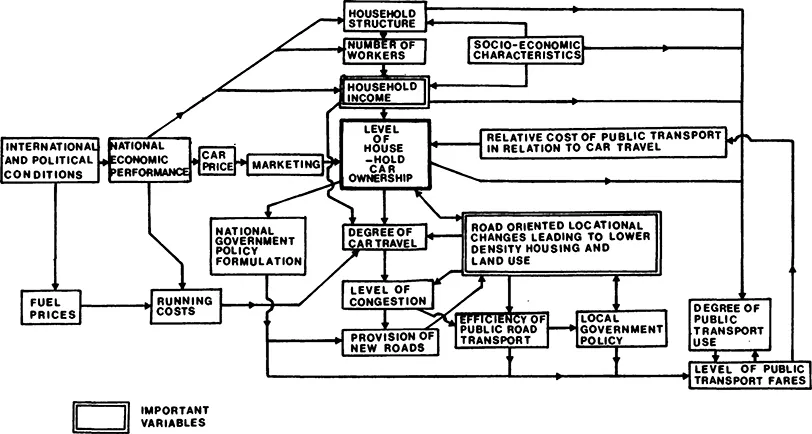

FIGURE 1.1 Factors influencing the level of car ownership.

To a much greater degree than exists in modern times, and refuting some of the logic applied to present day patterns, there was a notable regional variation in ownership levels as is shown by Figure 1·2. Under such conditions, any attempt at national forecasting on the basis of aggregation of data was liable to misuse, though there is little evidence that central governments expended very much energy on road and traffic matters, other than in the area of road safety, until the changing pattern of car ownership and use became evident in the late 1950s. What limited forecasting there was soon proved to be widely inaccurate and reflected the rule-of-thumb philosophy upon which it was based.

In 1929 (with annual registrations still falling but with nearly a million cars already in use) the SMMT [Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders] continuously revised their estimate of saturation point to a million and a quarter (from an earlier 1927 estimate of one million). From 1932 sales began to pick up again at an ever-increasing rate. The Economist expressed astonishment at the resistance of the motor industry to the depression. There were a million and a quarter cars — “saturation point” — on British roads by 1934; by the time the war began there were over two million. (Plowden, 1971, p. 264.)

FIGURE 1·2 Variation in car ownership in selected areas in 1927.

It is clear that there were problems in estimating that parameter which has been a continual source of debate over the past twenty years, namely saturation point, or that level of ownership which reflects a stable ratio of cars per head of population with no latent desire for car ownership on the part of any group or individual within that population. The situation in the 1930’s provides an interesting comparison with more recent assumptions on saturation levels. Pre-war commentators obviously assumed that car ownership was clearly beyond the means or desires of the working-class section of the community. In recent years, it has been assumed that the vast majority of the population desire car ownership or at least free access to private vehicle use, and that the final constraints are financial or related to age and physical ability to drive. Clearly, the popular ideas of the 1930’s suggest that any assumption regarding desire for car ownership should be open to modification in the light of experience.

Although the nature and scale of the problem differed considerably from that which faced transport planners in the 1960’s, it is clear that (in the 1930’s) there already existed some of the pitfalls of prediction based on apparently rational variables and relationships. The parallel between the inter-war period and the post-1973 economic “depression” is worthy of comment. In so far as a large faction of predictive researchers base their hypotheses on economic variables, any logical observation of the inter-war period, using economic data aggregated at national level, would have predicted a stagnant level of car ownership and use. In reality, spatial and social variations in income and purchasing power, coupled with other social and economic variables, resulted in a relatively high rate of increase in vehicle ownership (among the middle class) during the 1930’s.

The (already) well-established tendency to under-predict the growth of vehicle ownership was evident once again during the 1950’s, only now the “problem” was much more serious as ownership of motor vehicles began to extend beyond the bounds of upper and middle classes. It is clear that prediction procedures used in the 1930’s were based on a loosely accepted hypothesis of the relationship between ownership and income distribution and that although it is accepted that such a relationship does exist, ownership rose much faster than real incomes for a number of reasons. During the early 1950’s it was estimated that at least 50 per cent of vehicles were owned or partly financed by firms or business interests. Coupled to this was the influence of widespread use of hire purchase which predictions had not considered. So a familiar tendency to underestimate growth rates and saturation levels is evident during the period 1945-1960, forming only one aspect of a limited governmental involvement in the road transport problem. Contemporary predictions throw into relief the relative success which has been achieved on the basis of work carried out since 1962 at the Road Research Laboratory (RRL).

In 1945 the Ministry [of Transport] estimated that traffic increases by 1965 would be 75 per cent over 1933 figures in urban areas and 45 per cent more in rural areas; but by 1950 — five years later — the number of vehicles had already nearly doubled compared with 1933. In 1954 the Ministry told highway authorities to plan for a 75 per cent increase in traffic by 1974. But by 1962 the number of vehicles was already 75 per cent above the 1954 figure. In 1957 the Ministry forecast that there would be eight million vehicles by 1960; but there were 9 million. In 1959, the Ministry of Transport forecast that there would be 12½ million vehicles by 1969, but this figure was passed in 1964. (Tetlow and Goss, 1968, p. 83.)

Other government policies on transport, and road provision in particular, reflected the assumptions inherent in these predictions.

Views about the relationship of motoring to both class and income — and probably also the residual notion that car ownership is a luxury of which the state, in providing for the necessities of life, need take no account — were built into the provision of garage space and of roads in public housing developments. (Plowden, p. 327.)

As far as road construction is concerned, the story of inactivity and piecemeal investment during 1945-58 is well known and needs no expanded treatment. Legal powers to build motorways existed under the Special Roads Act of 1949 but it was not until December 1958 that the first section of motorway was opened.

The need for accurate and more dependable prediction led to new pressure and research interest with the first consideration of overseas (particularly USA) experience. The justification for accurate and soundly based prediction has not changed, only become more valid, as pressure on space and resources has increased to the extent that the rule-of-thumb techniques of the 1950’s are totally inadequate. The vast amount of academic research activity of a statistical and economic nature may be justified solely on the grounds of reducing the probability of a slight percentage error, perhaps saving millions of pounds’ unnecessary expenditure.

The 1950’s also witnessed greater involvement in forecasting on the part of staff of the United Kingdom Road Research Laboratory. Although primarily concerned with growth rates in overall vehicular traffic some coverage was afforded to the specific problem of explanation of car ownership notably by Rudd (1951) and Reynolds (1954). These commentators gave only approximate estimations of future levels of ownership. More detailed projections were produced by Chandler (1958). Using a number of methods, including extrapolation, he concluded that, by 1968, the number of vehicles in use would reach more than ten million, possibly twelve million (the actual GB 1968 figure was 14.4 million).

The problem of provision of scientifically derived forecasts also received attention from Tanner (1958). On the basis of an analysis of growth patterns in the USA and parts of the UK, he noted that areas with higher levels of ownership tended to exhibit lower rates of growth, indicating evidence of a declining demand for first cars as a situation of “saturation” approached. Several linear extrapolations of this trend produced tentative “saturation levels” which would be achieved when the rate of growth fell to zero. Tanner postulated that growth in the UK could be expected to follow a curve exhibiting logistic characteristics, its shape being controlled by three parameters — base year rate of ownership, base year growth rate, and saturation level. Using a 1957 base this procedure was used to predict a 1975 forecast of 16.4 million vehicles (this compares closely with the actual 1975 value of 17.5 million). (Full details of the Tanner logistic procedure are discussed in Chapter 2.)

Within the United States, however, several authorities had already set about more detailed examinations of growth trends in car ownership and other consumer durables and it was in the latter field that much UK work was based prior to 1960. Some of this work pre-dated the Second World War, notably that of de Wolff (1938).

De Wolff used a time-series extrapolation of demand for new cars based on patterns of scrapping and replacement during the period 1921-1934. It was unfortunate that the time period chosen (available) coincided with economic conditions which were not typical of the postwar period, making the analysis largely invalid as a predictive exercise, but his use of a logistic growth curve for car purchase established a precedent in this field which was followed very vigorously by the Transport and Road Research Laboratory (UK) more than twenty years later.

In the immediate post-war period, a limited amount of research was carried out on the problem, mainly in the United States. There was a distinct tendency to look for economic explanations of existing trends. Typical is the work of Farrell (1954), who paid particular attention to economic explanation for changes in demand for cars. In classifying motor cars in the same category as other consumable durables, Farrell was guilty of an invalid assumption exposed by later researchers (notably Cramer, 1962) and in any case his work was largely concerned with an historical examination of trends in the USA between 1941 and 1953. He made no attempt to make any prediction of future rates of vehicle purchase and levels of ownership. Indeed Dawson, in the “discussion” which followed the presentation of Farrell’s paper, noted the difficulties resulting from regarding motor cars as typical consumer durables. Not only was the concept of a saturation level less acceptable, but, already by the mid 1950’s, the market in second-hand vehicles was of a size quite incomparable with any other durable such as washing machines or vacuum cleaners. This feature of the motor vehicle market has remained a notable constraint on analogous studies.

During the same period, Cramer was working on a similar area of study in the UK which produced a general economic model for ownership of consumer durables. This took into account household size and type of residential area as the major determinants of ownership of consumer durables. The study had already made an a priori assumption that in fact the nature of demand for motor cars was inherently different from that for other goods, on account of their special qualities and the non-economic benefits ownership conferred. So any attempt to compare growth rates and distribution patterns for cars on the one hand and television sets (for example) on the other led ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of contents

- Series Editors’ Introduction

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Modelling in the UK 1900-1960

- 2 The Road Research Laboratory Model and its Development to 1973

- 3 Econometric Modelling and the Problem of Disaggregation

- 4 The Impact of Government Intervention

- 5 A Review of US Modelling Prior to 1962

- 6 Recent Developments in the USA and Australia

- 7 National Theory: Local Practice

- Conclusion

- Additional References

- Appendix 1: Summary of the TRRL Logistic Curve Procedure

- Appendix 2: Population Projection Methods used in the UK

- Appendix 3: Car Ownership in the USA and UK 1900-1979

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Car Ownership Forecasting by E. W. Allanson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.