- 548 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

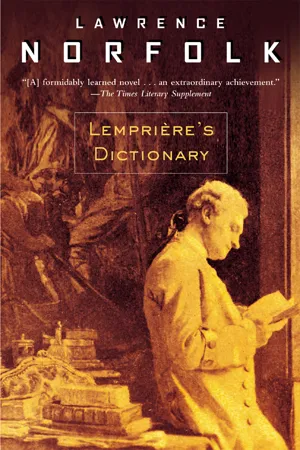

Lemprière's Dictionary

About this book

The Somerset Maugham Prize–winning, international bestselling debut novel: "a dazzling linguistic and formal achievement" set in 18th century London (Salman Rushdie).

In eighteenth-century London, John Lempriere works feverishly on a celebrated dictionary of classical mythology that bears his name. But when he discovers a conspiracy against his family dating back 150 years, he embarks on a personal mission that will pit him against enemies he never new he had, allies he never thought he would ever want, and a destiny he never imagined . . .

Told with the narrative drive of a political thriller and a Dickensian panorama of place and time, this "superbly entertaining" tale encompasses multinational conspiracies and a motley cast of scholars, eccentrics, prostitutes, assassins, drunken aristocrats, and octogenarian pirates—all brilliantly depicted across three continents and the world of classical mythology ( The Washington Post).

In eighteenth-century London, John Lempriere works feverishly on a celebrated dictionary of classical mythology that bears his name. But when he discovers a conspiracy against his family dating back 150 years, he embarks on a personal mission that will pit him against enemies he never new he had, allies he never thought he would ever want, and a destiny he never imagined . . .

Told with the narrative drive of a political thriller and a Dickensian panorama of place and time, this "superbly entertaining" tale encompasses multinational conspiracies and a motley cast of scholars, eccentrics, prostitutes, assassins, drunken aristocrats, and octogenarian pirates—all brilliantly depicted across three continents and the world of classical mythology ( The Washington Post).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

III Paris

TO PARIS, by pacquet-boat from Saint Helier to Saint Malo, by coach along the stages of the Normandy road, wheels clattering over a metalled surface rolled out of Trésaguet’s tripled-tiered genius and the corvée labour system like carpet through mile after mile of flat grey skies and avenues of plane trees and Lombardy poplars, with outriders making up an escort though no-one is encountered for leagues except capped and smocked peasants toting sickles and scythes for the late harvest who wave the mail through by reflex, grinning, waving, scything: Le Nain country.

On, into the interior, Île de France, where the terrain becomes more intensely rural, pigs, cows, sheep, fields of sorrel shaking in the slight gusts that freshen the shallow slopes the road cuts through and clouds of chickens thrown up by the coach’s commotion tumbling about in the air, apple trees too and stunted vines pushing branches out of the earth like the arms of the dead, flat lawns and neglected parterres. It all helps, even the skies which are still lead-grey, even the peasants though they contribute less, scarcely looking up as the coach approaches the metropolis, their oppidan indifference is a sign meaning the city is not far off and a little later a purple-grey smudge up ahead on the horizon confirms this, four or five hours away at the most. It is late autumn.

Inside the coach, the two passengers sensed its approach as it crept closer towards them, Paris, city of white plaster walls, leaning tenements and the Palais Royale where the two of them will later stroll and admire the treillage and horse chestnut trees, guess at the humbler structures which will turn out to be extraordinary, though in different ways, trumpet schools, a wallpaper factory, or an entrance to the catacombs which riddle the city guts with passages and channels, for the soil is very chalky and buildings have been known to disappear overnight, or even in broad daylight - it is a city of sudden collapses and rumours of collapse which turn out to be true. Streets run into each other like old friends penetrating one another’s motiveless disguises (later they realise they were sent by distant rival-monarchs to destroy one another), geometry can no longer account for the angles at which they meet but the bonus of constantly surprising and unexpected vistas which this non-plan implies is always around the next corner, always waiting, always deferred. Awful boredom hangs over the place like smoke and even if the fact that the city looks like it were dropped from a great height and shattered into a thousand pieces were true, this too, even this cataclysm, would be dull. The roads which converge on the city from all directions except the north-west and confirm it as the centre of attention do so from necessity, injecting provincial vigour and rough rural bonhomie without which it would grow confused and sluggish and eventually come to a complete halt with everyone frozen forever in place like Phineus and his men turned to stone at the wedding of Danae’s son. At some deep substratum of its soon-to-be collectivised subconscious the metropolis knows and resents this fact, metabolising it as hauteur. The arteries carrying in its life from the outlying districts constrict as they approach their goal, intensifying the commerce of coaches, wagons, cabriolets and post-chaises until they jostle and knock against each other, making their drivers ill-tempered in a frantic preparation for their syringing into the stone scab of the city itself. A rampart of refuse which the city voids and pushes out and which grows a little higher day by day rings the area, somehow investing it with the spurious allure of a walled garden in which, rumour has it, pale-looking young men might pay fruitless attentions to vicious Arabic beauties and neglected orange trees nevertheless bear fruit year after year after year, great rotten-ripe segments fall away from their mouths and everything could turn to dust around them, they would not care, nothing matters. Paris. City of lovers, which the coach has entered by the Rue de Sévre, its pace slowed to a walk by the drovers and carters. Juliette angled her head against the glass to watch the city as it lumbered towards them, its spires and rooftops drawing her eye this way and that until there was nothing but buildings all about them, the driver was passing through the toll gate and they were inching through streets crammed with flower sellers, letter writers, women selling pastries and men selling herrings spiced with vinegar and chives. The smell made her remember everything. The coach came to a halt in Rue Notre Dames des Victoires and she stepped onto the ground which became hard and real beneath her feet, crystallising into Paris, suddenly the city of her return.

Behind her, the other passenger climbed out more slowly. They had been on the road from first light and now it was late in the afternoon. Jacques watched the girl as she strode about at the back of the coach gabbling in French, pulling the men this way and that as they unloaded the cases, hailing an open carriage. Her activity came in flurries, he had noticed, with periods of lethargy when nothing would animate her but a barked command. Casterleigh’s work, he thought, or the past encounters he had not witnessed and at which he could only guess. The journey from Jersey had exhausted him, though smooth enough compared to the last. He was growing tired of it, but this was the last time, if all went well.

‘Wait!’Jaques shouted across to the girl, who froze and looked back over her shoulder with the face of a thief. Casterleigh again. Leaving his stamp. Jaques pointed to the girl’s own case which still sat on the cobbles at the rear of the coach. Battered canvas, a cheap thing. She had hugged it to her all the way from Saint Helier, it had blue flowers painted on its side which were all but faded away.

The house lay a quarter of a mile away, across the Rue Montmartre in a court off the Rue du Bout du Monde. It was entered via a courtyard. The porte-cochère’s heavy gates were closed behind them as the carriage rolled through, a three-storey villa, plastered white with the lower windows protected by iron grilles set into the stonework. The footmen were waiting to unload the baggage. Stable lads unharnessed the horses. Inside, the maids curtseyed to Juliette before going about their business. A faint smell of dust hung in the air. She could hear pails and mops clattering somewhere out of sight. The house had lain empty and was now being opened for the two of them. Other than the servants they were the only occupants. Jaques had already disappeared. She was alone in the entrance hall with her cases and a footman who waited quietly at the foot of the staircase, the familiar scene, tens, perhaps hundreds of such halls, cool echoing interiors with alabaster columns and Japanned urns, intricate stucco work, and herself, waiting for the serving man who would fetch her upstairs in silence only broken by their footsteps.

This time it was he who waited for her, but the silence was unchanged as she motioned him to guide her to her room where a maid stood in attendance, curtsied and began to unpack the cases. She clutched the canvas bag to her chest. High windows looked south, out over the city with its rooftops which looked like scales, the river and the spire of Notre Dame, until the detail was lost in distance and the onset of evening. Between her vantage point and the spire lay the Marché des Innocens, just beyond that the tangle of streets bounded by the Saint Denis highway and Quai de la Mégisserie. She might have reeled off every street in that quarter, every ally, court, even the nameless passages that connected some of the establishments with discreet back entrances onto the quieter thorough-fares. She knew them all, running through with her playmates who stank of the river, scabs on her knees and her hair cut like a boy’s, pretty even then. They had watched as the floods brought small boats crashing down the river and cheered as they splintered against the stones of the Pont Neuf. Her mother had cuffed her till she saw double but she had forgotten why, almost forgotten when. Almost forgotten Maman.

‘Mademoiselle?’

‘Yes, yes of course.’ The maid was finished. A pier-glass mounted on the wall between the windows threw back her reflection. There she was, brought back for a purpose. The Viscount knew but would not tell. She had known better than to ask as they took the carriage down to the waiting boat. He had spoken with Jaques on the jetty. She had watched through the window, then Jaques had taken her back to the house. The Viscount’s departure sharpened her vague sense of betrayal, for she already sensed a new phase in their relations and heard the clatter of gears changing. She thought of the pool. The water had been very cold and when the man, barely a man then, had flopped over and his arm had come up with its hand shredded to rags, she had thought of her own body, white, naked in the water which held her like weights around her ankles. More and more he was the Viscount; not Papa at all. He would be one then the other, she could not follow and was left floundering in his disapproval, a coquette, a precocious harlot all out of step, but in the pool she was frightened in a new way. Later, he had shot the dogs. She had sat in her room. It had taken an hour and each time the gun cracked she had jumped, then tried to settle but all the time waiting for the next report which would jerk her back to the moment in the pool when she had looked up at him on the horse and he had looked down at her and she saw the aftermath of a decision in his face. She was alone and naked and the dogs were there, aimless, waiting; the decision had gone her way. The gun cracked and she jerked again. It was the boy’s father, but she had guessed that. Later, when she went to the Viscount, he had told her that the boy had seen it all. That was the point. She was ashamed he had seen her. Casterleigh had become Papa again, tender or stern as the situation demanded, no longer the Viscount, just as he had been when she had told him what father Calveston had told her, what Lemprière had told him.

‘Visions?’ he had demanded.

‘He reads things. He believes they come true….’

‘What things?’

The man turning over. The dogs eating him. Letters had been sent to men in London and he had become the Viscount once more, raging and cursing. Children’s games. He wanted to kill the boy and the letters told him no. Juliette spied on him hunched over his desk like an animal with the letters in his fists, little bits of paper telling him no, and the boy was still alive. Jaques had told her during their weeks together on Jersey. The boy had sailed for England, for his father’s will. She and Jaques had left for France a fortnight later. There would be a reason for both these things. There was a reason for the dogs drifting harmlessly back through the stream towards their master, leaving her there shivering, unmarked in the water; reasons like the bits of paper in his fists keeping Lemprière alive. The men in London, his partners, had told him no.

The maid had returned. A meal had been prepared for her on Monsieur Jaques’ instructions. Juliette gave up her thoughts and followed the woman to the dining room where a long mahogany table was laid for one. Monsieur Jaques had gone out. Juliette ate alone and in silence only broken by the servants as they brought in dishes she remembered: spiced mutton and ham, sweet white onions. When she had finished, Jaques had still not returned. It was quite dark now. The lamps had been lit and Juliette wandered through the house, drawn from room to room by a curiosity which only intensified as one by one, their contents told her nothing; rooms furnished with bow-fronted sideboard tables and fiddle-backed chairs carved from rosewood. There were damask-covered sofas and plain chests of drawers. The pictures on the walls were of old dukes, Rohan, Orléans, Barry and Condé whose woods they had passed through near Chantilly, Jaques had said. Framed charts lined an upper corridor which seemed to stretch the length of the western seaboard of France; Le Havre, Boulogne, Calais, Cherbourg, La Rochelle. They told her nothing. The room at the far end of this passage was a large study, but the desk was bare, its drawers locked and, she suspected, empty too. Leather-bound books lined the walls behind it. They still had their sheen, new, she thought, then fakes. No, they were simply unread. Her finger dawdled along the tooled leather spines with the names picked out in gilt letters, beautiful, all Greek and Latin. Anthologies of fragments. They were ranged chronologically along the shelves and as her eye skipped along the names she realised that she had written them all down, the day Lemprière had come to visit, in the library on Jersey. He had pushed these books through Quint’s protests like battering rams, humiliating him. So he had teeth after all, in a way. Lemprière’s books: growing wings or horns.

‘He reads them. And he believes they come true.’ The dogs rounded and trotted back to their master. Lemprière: his thoughts were in the trees of that scene, in the pool, the dogs, even in Casterleigh and herself. All his dreams came true, they were all here. In the pool she was at their centre. The Viscount’s decision and Lemprière’s dreaming her there shuttled her this way and that at their behests while the dogs pulled the body apart. She was them both somehow, all their choices. It was a new phase. Papa was gone. There was only the Viscount now, and Lemprière.

Her search had taken her to the top of the house. From there, she heard a coach enter the courtyard far below. Juliette slipped from her perch on the desk and ran lightly down the corridor and stairs.

When Jaques entered the entrance hall she was preparing for bed, seated at her dressing table, picking pins out of her hair. They made tiny clinking sounds as she dropped them one by one into a small glass tray on the table. She was combing her hair. Jaques was in the doorway, she saw him in the mirror. Jaques was almost bald, he had a soft intelligent face. He was hanging there, neither in nor out of the room. She turned to look at him, surprised, she had not thought this required of her. Her comb had caught, she had missed a pin and drew it out carefully with her head bent down. Her hair hung down her back, click, she looked up once more at the slight sound. He had closed the door. The pin fell with the others, ting, into the tray. She looked around. Jaques was gone.

The following morning found them strolling arm in arm in the triple avenue of the Cour de la Reine. She was his daughter, his ward, a favoured niece, some or all of these as they drifted back along the Port aux Pierres and up into Place de Louis Quinze. Later they admired the arcaded houses which had gone up on three sides of the Tuileries. The next day was much the same, walking along the Quai Pelletiers with the gamblers playing passe dix and biribi seated on folding stools amongst the herring racks.

Other days, other sights. When the November skies threatened rain she her hair dressed at Baron’s. They ate at the Véry or Beauvilliers and watched the learning riders fall off their mounts at Astley’s. Juliette, for whom routine was a series of coincidences strung together, found it unsettling. In the evenings they played trente et un at Madame Julien’s, or dominoes at the Chocolat Café, or they went to the theatre. Sometimes she was left alone. There was a calculated aimlessness to their days. Each one, somehow, was a facsimile of the last. Only the details varied.

The days became weeks. Their vague rambles through the streets became vaguer still as though any sort of planning or forethought was forbidden and they found themselves in the Halles or Courtille districts where Juliette would never have ventured of her own accord, or walking through streets where the sewers were choked with straw, animal droppings and offal. There seemed no point or design to these tours, except that not once did they venture into the area below the Marché des Innocens, which she had viewed at a distance on her first evening. They would take long exhausting detours to avoid it, and the sight Juliette dreaded was never encountered. Casterleigh would have told him, must have told him. ‘Papa’ once more, perhaps.

They were watched. She could not be certain - they were always different - she caught them in the corners of her eyes just within earshot and at irregular times, in places which signified nothing. She kept her peace about them; another component to be weighed up and fitted into the puzzle with the others, like Lemprière’s list of books turning up in the study. Their aimlessness, their waiting, their watching; some central task, some event would link them but she did not know what. Her role was changed, she was a stranger now. Her first embrace, when the city pressed itself right up against her as she stepped from the carriage, that was gone. She was drifting and floating. Somewhere in these repetitious dawdling days the two of them had come apart. Even the watchers were falling away, or blending more successfully into the crowds. The time was filled with events and diversions, things they had done, or avoided doing. Somewhere in it all was a point.

D...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- 1600: The Voyage Out

- I Caesarea

- II London

- III Paris

- IV Rochelle

- 1788: Settlement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lemprière's Dictionary by Lawrence Norfolk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.