![]()

1

A HISTORY LESSON

Chicago will give you a chance. The sporting spirit is the spirit of Chicago.—Lincoln Steffens

It's hard to imagine now, what with buildings that scrape the sky and elevated trains that rumble high overhead, but Chicago was an unlikely place for a city. It had no plan, no particular destiny. It wasn't until it was experienced and molded by men that this land held any fate. Take away the buildings, the boats and the miles of railroad lines and imagine instead a swampy bog inhabited by a few Native Americans. In the warm months, Indians did their fur trading up and down the river that wound its way through the prairie. In the cold months, even the Indians would skip town. The howling winter winds would shoot across the color-stripped plains, and in summer, the prairie grass would sway in the lake breeze. This breeze carried the scent of a foul-smelling onion the Indians called checagou—and with that, Chicago was born with a joke on its lips. A global city known for its architecture, business and big shoulders was named after a particularly smelly onion. Good one Chicago, good one.

The first white men to come to Chicago were two Frenchmen sent by the governor of France to explore new lands for expansion. Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet arrived here from Green Bay in 1674. They were impressed with the abundance found on the prairie land. Bison roamed free, and the soil grew corn and wheat easily. As Marquette and Jolliet made their way back to France—probably thinking about Chicago, “Meh, it was okay”—the two men were shown a shortcut, a portage that linked the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. Anywhere a canoe could be carried to connect two waterways was precious. Water was transportation, and transportation meant business; thus, a portage was a valuable asset. Both Marquette and Jolliet knew they had found an important spot, a spot that shivered and shook with the anticipation of growth. Once home, Jolliet pressed the French to build a canal to create a direct waterway between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, a canal that would connect east to west. Alas, the canal would not be built by the French.

Jolliet had seen the seed of Chicago's power, and this was all that was needed to spark the fire. Chicago was obscure no more. Only nine years after Jolliet and Marquette, another French explorer, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, began to map the land, and he too saw, perhaps better than anyone, a destiny for the invisible city:

This will be the gate of empire, this the seat of commerce. Everything invites to action. The typical man who will grow up here must be an enterprising man. Each day as he rises he will exclaim, “I act, I move, I push,” and there will be spread before him a boundless horizon, an illimitable field of activity.1

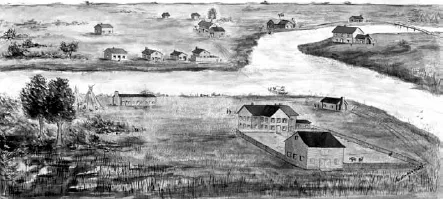

The first permanent settler was Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable, a French-Haitian black man who built his house at the mouth of the Chicago River about 1770. He made his living trading furs and goods with the Indians and the few travelers in the area. Generally, it was a quiet, if cold, existence. In 1804, Fort Dearborn, Chicago's first permanent structure, was built at the corner of modern-day Wacker and Michigan Streets. Fort Dearborn was all about the portage; the Americans were catching on to its possibilities, and the fort was built to protect the portage from the Indians. In 1812, after a bloody attack, Fort Dearborn was burned and then rebuilt in 1816. In 1818, Illinois was incorporated as a state, and by 1837, the year of Chicago's incorporation as a city, this tiny, fur-trading spot had grown in population to roughly four thousand people, mostly French and French-Indians plying their trades on the lethargic and lazy river.

The early days of Chicago were harsh ones. It was not easy to live on this hostile land. Settlers were isolated from much of the world and living without the rules and laws of polite society. Still populated by a racy mix of French and Indian traders, the only real relief from the elements came in the disguise of the local saloon. Chicago's first entrepreneur was a man named Mark Beaubien, who built the Sauganash Hotel on Wolf Point at the confluence of the north and south branches of the Chicago River. Although it sounds like a respectable place, the Sauganash was “an impressive structure in the town, it was more of a frontier tavern with rooms above it than the eastern image of a hotel.”2 Mark Beaubien was the epitome of an early Chicagoan; “to old settlers, he was ‘our Beaubien,’ part civilized, part savage in spirit, a reckless but lovable man who managed to spend whatever he made.”3 Soon, Beaubien, father of a whopping twenty-three children, found he was flush enough to open a saloon next to his hotel. Men and women—because all were welcome in this lawless frontier town—went to the Sauganash to drink and dance. White men danced with Indian women, and drink was plentiful. The Sauganash was a rowdy place, and its most sophisticated form of entertainment consisted of Mr. Beaubien pulling out his fiddle and playing a rollicking song for his patrons. Sometimes, just to mess with the easterners, white men would dress up as Indians and enter the saloon hollering and hooting, scaring the big apple right out of those New Yorkers.

Chicago in its early stages. The Sauganash Hotel can be seen in the foreground. Photo courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

As Chicago grew, so did its relationship with New York City. New York was a much older city; its first colonies were settled in 1624 by the Dutch. New York had strong ties to Chicago and wanted and needed it to do well. In City of the Century, Donald Miller notes, “New York, the busiest ocean harbor in the world, and Chicago, the busiest inland harbor in the world, became linked by nature and man, their economic destinies intertwined. Throughout the nineteenth century, as Chicago prospered, so did New York; and vice versa.”4 Land grabbing in Chicago was at an all-time high. Men could make fortunes in a matter of minutes. Easterners were coming to buy and sell land in the town, so their profits were linked to the success of the land they purchased. It was important Chicago succeeded. The relationship with New York would continue as not only a bane to Chicago's existence but a boon to it as well. New Yorkers brought their eastern ways with them, and in the case of Mark Beaubien, the arrival of easterners forced his early exit. He left for Naperville claiming he had to leave Chicago because he “didn't expect no town.”5

As New Yorkers spilled into the lawless city of Chicago, they yearned for more culture than Chicago could offer. Devoid of theaters but flush with saloons, proper entertainment in Chicago was difficult to find. New Yorkers had grown used to paying for and enjoying the refined theaters of New York City, but Chicago was still so young and base that its residents showed their love for performance by yelling and banging on tables at the Sauganash. There were a few performances by traveling entertainers who made their way to Chicago, usually one-man shows that specialized in a variety of fascinating spectacles for the audience. On February 24, 1834, the first performance that required actual payment was held in the private home of Dexter Graves. A Mr. Bowers was to arrive and “introduce many very amusing feats of Ventriloquism and Legerdemain, many of which are original and too numerous to mention…Performance to commence at early candlelight.”6

Chicagoans learned early on that a sense of humor was essential to living in a struggling frontier town in 1834. As Chicago's population increased, the muddy streets became a hazard. Farmers and horses both would get stuck in the knee-deep mud that arrived every spring. Huge holes would appear where horses and wagons were dug up out of the mud. Chicago's first comedians left signs saying, “No Bottom Here” or “The Shortest Road to China.”

![]()

2

THE SAVAGE TAMED

I have struck a city—a real city—and they call it Chicago…I urgently desire never to see it again. It is inhabited by savages.

—Rudyard Kipling, American Notes

It is important when talking about the history of Chicago comedy to start with the theaters that made their home in the city. Since very few people actually settled in this frontier town, it was the theater managers who dictated style and form. Individual performers came from all over, often passing through from other small towns. Specific performers are hard to track considering they had stage names and were never in town for long, blowing out as the winter winds blew in.

A few years after Chicago's incorporation in 1837, the first permanent theater group arrived—no doubt the influence of easterners searching for a new place of entertainment. The new theater group called itself the Chicago Theater. Mr. Harry Isherwood, the founder of the group, came to Chicago to see if it was a suitable place to open his new theater. But unlike the hopeful words of La Salle, Isherwood's words conveyed his shock at the state of the frontier town:

In 1837 I arrived in Chicago, at night, and was driven to a hotel in the pelting rain. The next morning it was still raining. Went out to take a view of the place. A plank road, about three feet wide, was in front of the building. I saw to my astonishment a flock of quail on the plank. I returned to my hotel, disappointed at what I saw of the town, and made up my mind that this was no place for a show.1

Yet Isherwood and his partner, Alexander McKenzie, stayed and housed the Chicago Theater group in the dining room of the vacated Sauganash Hotel. They put on a few plays like The Idiot Witness, a comedic melodrama; The Stranger; and The Carpenter of Rouen. The bill would change every night, as Chicago audiences weren't patient enough to have it any other way. After six weeks, the company went on tour, and when it came back in 1838, it made its new home in the Rialto.

The Rialto was “a den of a place, looking more like a dismantled grist-mill than a temple of anybody.”2 It wasn't a fancy theater; in fact, it was originally an auction house named for the part of town where it was located. It had four walls and flimsy wood—not so different from the small, independent theaters of today. But no matter, Isherwood and McKenzie worked with what they had and added a gallery and a pit to create a real theater experience. The four-hundred-seat theater changed its name to the Chicago Theater, no doubt a more cosmopolitan name than the Rialto. Isherwood and McKenzie did their best to bring an air of sophistication to the city. Instead of hiring the variety acts normally seen in saloons, they put on scripted plays, a practice many of the new elite found more appropriate.

The new culture emerging in Chicago saw drama as a serious undertaking to be experienced in a proper theater. But comedy, the hedonistic art form that it was, was relegated to the saloons. Women used to dance and sing along with the men in the old days of the Sauganash, but that was no more. Women appearing in saloons was frowned upon now. Men would go to the saloons for a respite from the hardscrabble days of battling a new frontier and, more likely, to get away from their wives. To the saloons they would go for their nightly liquor and ladies of the night. To keep the men entertained, variety performers of all sorts would play instruments, tell jokes and sing songs. Tim Samuelson, city historian, says:

There are references to people who had routines where they would dress up as a character or come out and do observations also combined with music. It's not like the divisions of what kind of performer you were were really clean. Even the people who performed would often combine things, so you would get up and make an observation about the time or politics and then break into a song.3

The men of Chicago would let it be known if they liked a show by throwing their money on stage—or fruit if they didn't. And in a move that would reverberate for the next 150 years, many of the men would participate in the show, running up on stage or influencing the show from the audience. Chicagoans always let it be known what they thought of their local theater, and from then on, the actors on stage began to listen.

Isherwood and McKenzie wanted to stay away from the base comedy being performed at the bars; they wanted to attract the new elite. They found it helpful to put on shows that were already popular in New York. Theater managers in Chicago also employed “stock stars”—actors who were well known around the country. These stock stars began to populate Chicago's theaters and gave the theater scene a boost in respectability. Although these stock stars tended to eat up money that Chicago certainly didn't have, the city wished to present itself as grown up. If Chicago liked what New York already adored, then it was on the right track.

A young family of actors by the name of Jefferson traveled with Isherwood and McKenzie. Joseph and Cornelia Jefferson arrived in Chicago with their daughter and nine-year-old son. Upon arriving, Joseph Jr. described Chicago as “a busy little town, busy even then, people hurrying to and fro, frame buildings going up, board sidewalks going down, new hotels, new churches, new theaters, everything new.”4 Joseph Jr. learned quickly how to entertain the audience members so they would throw coins in appreciation. Isherwood and McKenzie used the boy to fill out scenes or add a comic song to a particularly long drama. Joseph became quite adept at the stage and later in life became one of the great comedic actors of his time, known mostly for his roles as the gravedigger in Hamlet and his impression of Rip Van Winkle. Joseph Jefferson's name is immortalized in the annual Joseph Jefferson Awards, Chicago's version of the Tony Awards.

Isherwood and McKenzie were reasonably successful in Chicago, but they found that the winter months made it impossible to be profitable. Chicago's measly four thousand people weren't enough to sustain a permanent theater. They were losing money, and the traveling circuit called to them again. They left the Chicago Theater in 1839, and it was turned back into an auction house; obviously, a theater was not the best business proposal for a city like Chicago. Chicago went back to its circuses and saloons, forgetting temporarily about its foray into proper comedic theater.

Chicago didn't see another major theater again until 1847, when John B. Rice, a New York transplant, built the Rice Theater. Managing a theater was a full-time job, and Rice, like most theater managers at the time, was an actor, scene painter and anything else that was needed. Apparently,...