- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

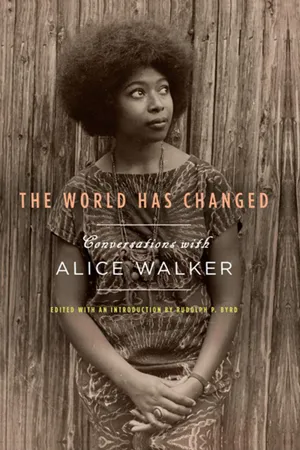

About this book

The National Book Award– and Pulitzer Prize–winning author’s fascinating and far-reaching conversations with acclaimed writers and thought leaders.

Spanning more than three decades, this collection of fascinating discussions between Alice Walker and renowned writers, leaders, and teachers, explores the changes that Walker has experienced in the world, as well as the change she herself has brought to it.

Compelling literary and cultural figures such as Gloria Steinem, Pema Chödrön, and Howard Zinn represent a different stage in Walker’s artistic and spiritual development. Yet, they also offer an unprecedented look at her career and political growth. Noted literary scholar Rudolph Byrd sets Walker’s work into context with an introductory essay, as well as with a comprehensive annotated bibliography of her writings.

“Read as separate pieces, these conversations offer vivid glimpses of Walker’s energetic personality. Taken together, they offer a sense of her marvelous engagement with her world.” —Kirkus Reviews

Spanning more than three decades, this collection of fascinating discussions between Alice Walker and renowned writers, leaders, and teachers, explores the changes that Walker has experienced in the world, as well as the change she herself has brought to it.

Compelling literary and cultural figures such as Gloria Steinem, Pema Chödrön, and Howard Zinn represent a different stage in Walker’s artistic and spiritual development. Yet, they also offer an unprecedented look at her career and political growth. Noted literary scholar Rudolph Byrd sets Walker’s work into context with an introductory essay, as well as with a comprehensive annotated bibliography of her writings.

“Read as separate pieces, these conversations offer vivid glimpses of Walker’s energetic personality. Taken together, they offer a sense of her marvelous engagement with her world.” —Kirkus Reviews

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Interview with John O’Brien from Interviews with Black Writers (1973)

JOHN O’BRIEN: Could you describe your early life and what led you to begin writing?

ALICE WALKER: I have always been a solitary person, and since I was eight years old (and the recipient of a disfiguring scar, since corrected, somewhat), I have daydreamed not of fairy tales but of falling on swords, of putting guns to my heart or head, and of slashing my wrists with a razor. For a long time I thought I was very ugly and disfigured. This made me shy and timid, and I often reacted to insults and slights that were not intended. I discovered the cruelty (legendary) of children, and of relatives, and could not recognize it as the curiosity it was.

I believe, though, that it was from this period—from my solitary, lonely position, the position of an outcast—that I began to really see people and things, to really notice relationships and to learn to be patient enough to care about how they turned out. I no longer felt like the little girl I was. I felt old, and because I felt I was unpleasant to look at, filled with shame. I retreated into solitude, and read stories and began to write poems.

But it was not until my last year in college that I realized, nearly, the consequences of my daydreams. That year I made myself acquainted with every philosopher’s position on suicide, because by that time it did not seem frightening or even odd—but only inevitable. Nietzsche and Camus made the most sense, and were neither maudlin nor pious. God’s displeasure didn’t seem to matter much to them, and I had reached the same conclusion. But in addition to finding such dispassionate commentary from them—although both hinted at the cowardice involved, and that bothered me—I had been to Africa during the summer, and returned to school healthy and brown, and loaded down with sculptures and orange fabric—and pregnant.

dp n="61" folio="36" ?I felt at the mercy of everything, including my own body, which I had learned to accept as a kind of casing, over what I considered my real self. As long as it functioned properly, I dressed it, pampered it, led it into acceptable arms, and forgot about it. But now it refused to function properly. I was so sick I could not even bear the smell of fresh air. And I had no money, and I was, essentially—as I had been since grade school—alone. I felt there was no way out, and I was not romantic enough to believe in maternal instincts alone as a means of survival; in any case, I did not seem to possess those instincts. But I knew no one who knew about the secret, scary thing abortion was. And so, when all my efforts at finding an abortionist failed, I planned to kill myself, or—as I thought of it then—to “give myself a little rest.” I stopped going down the hill to meals because I vomited incessantly, even when nothing came up but yellow, bitter bile. I lay on my bed in a cold sweat, my head spinning.

While I was lying there, I thought of my mother, to whom abortion is a sin; her face appeared framed in the window across from me, her head wreathed in sunflowers and giant elephant ears (my mother’s flowers love her; they grow as tall as she wants); I thought of my father, that suspecting, once-fat, slowly shrinking man, who had not helped me at all since I was twelve years old, when he bought me a pair of ugly saddle-oxfords I refused to wear. I thought of my sisters, who had their own problems (when approached with the problem I had, one sister never replied, the other told me—in forty-five minutes of long-distance carefully enunciated language—that I was a slut). I thought of the people at my high-school graduation who had managed to collect seventy-five dollars to send me to college. I thought of my sister’s check for a hundred dollars that she gave me for finishing high school at the head of my class: a check I never cashed, because I knew it would bounce.

I think it was at this point that I allowed myself exactly two self-pitying tears; I had wasted so much, how dared I? But I hated myself for crying, so I stopped, comforted by knowing I would not have to cry—or see anyone else cry—again.

I did not eat or sleep for three days. My mind refused, at times, to think about my problem at all—it jumped ahead to the solution. I prayed to—but I don’t know Who or What I prayed to, or even if I did. Perhaps I prayed to God awhile, and then to the Great Void awhile. When I thought of my family, and when—on the third day—I began to see their faces around the walls, I realized they would be shocked and hurt to learn of my death, but I felt they would not care deeply at all, when they discovered I was pregnant. Essentially, they would believe I was evil. They would be ashamed of me.

For three days I lay on the bed with a razor blade under my pillow. My secret was known to three friends only—all inexperienced (except verbally), and helpless. They came often to cheer me up, to bring me up-to-date on things as frivolous as classes. I was touched by their kindness, and loved them. But each time they left, I took out my razor blade and pressed it deep into my arm. I practiced a slicing motion. So that when there was no longer any hope, I would be able to cut my wrists quickly, and (I hoped) painlessly.

In those three days, I said good-bye to the world (this seemed a high-flown sentiment, even then, but everything was beginning to be unreal); I realized how much I loved it, and how hard it would be not to see the sunrise every morning, the snow, the sky, the trees, the rocks, the faces of people, all so different (and it was during this period that all things began to flow together; the face of one of my friends revealed itself to be the friendly, gentle face of a lion, and I asked her one day if I could touch her face and stroke her mane. I felt her face and hair, and she really was a lion; I began to feel the possibility of someone as worthless as myself attaining wisdom). But I found, as I had found on the porch of that building in Liberty County, Georgia—when rocks and bottles bounced off me as I sat looking up at the stars—that I was not afraid of death. In a way, I began looking forward to it. I felt tired. Most of the poems on suicide in Once come from my feelings during this period of waiting.

On the last day for miracles, one of my friends telephoned to say someone had given her a telephone number. I called from the school, hoping for nothing, and made an appointment. I went to see the doctor and he put me to sleep. When I woke up, my friend was standing over me holding a red rose. She was a blonde, gray-eyed girl, who loved horses and tennis, and she said nothing as she handed me back my life. That moment is engraved on my mind—her smile, sad and pained and frightfully young—as she tried so hard to stand by me and be my friend. She drove me back to the school and tucked me in. My other friend, brown, a wisp of blue and scarlet, with hair like thunder, brought me food.

That week I wrote without stopping (except to eat and go to the toilet) almost all of the poems in Once—with the exception of one or two, perhaps, and these I no longer remember.

I wrote them all in a tiny blue notebook that I can no longer find—the African ones first, because the vitality and color and friendships in Africa rushed over me in dreams the first night I slept. I had not thought about Africa (except to talk about it) since I returned. All the sculptures and weavings I had given away, because they seemed to emit an odor that made me more nauseous than the smell of fresh air. Then I wrote the suicide poems, because I felt I understood the part played in suicide by circumstances and fatigue. I also began to understand how alone woman is, because of her body. Then I wrote the love poems (love real and love imagined) and tried to reconcile myself to all things human. “Johann” is the most extreme example of this need to love even the most unfamiliar, the most fearful. For, actually, when I traveled in Germany I was in a constant state of terror, and no amount of flattery from handsome young German men could shake it. Then I wrote the poems of struggle in the South. The picketing, the marching, all the things that had been buried, because when I thought about them the pain was a paralysis of intellectual and moral confusion. The anger and humiliation I had suffered was always in conflict with the elation, the exaltation, the joy I felt when I could leave each vicious encounter or confrontation whole, and not—like the people before me—spewing obscenities, or throwing bricks. For, during those encounters, I had begun to comprehend what it meant to be lost.

Each morning, the poems finished during the night were stuffed under Muriel Rukeyser’s door—her classroom was an old gardener’s cottage in the middle of the campus. Then I would hurry back to my room to write some more. I didn’t care what she did with the poems. I only knew I wanted someone to read them as if they were new leaves sprouting from an old tree. The same energy that impelled me to write them carried them to her door.

This was the winter of 1965 and my last three months in college. I was twenty-one years old, although Once was not published till three years later, when I was twenty-four (Muriel Rukeyser gave the poems to her agent, who gave them to Hiram Haydn—who is still my editor at Harcourt, Brace—who said right away that he wanted them; so I cannot claim to have had a hard time publishing, yet). By the time Once was published, it no longer seemed important—I was surprised when it went, almost immediately, into a second printing—that is, the book itself did not seem to me important; only the writing of the poems, which clarified for me how very much I love being alive. It was this feeling of gladness that carried over into my first published short story, “To Hell with Dying,” about an old man saved from death countless times by the love of his neighbor’s children. I was the children, and the old man.

I have gone into this memory because I think it might be important for other women to share. I don’t enjoy contemplating it; I wish it had never happened. But if it had not, I firmly believe I would never have survived to be a writer. I know I would not have survived at all.

Since that time, it seems to me that all of my poems—and I write groups of poems rather than singles—are written when I have successfully pulled myself out of a completely numbing despair and stand again in the sunlight. Writing poems is my way of celebrating with the world that I have not committed suicide the evening before.

Langston Hughes wrote in his autobiography that when he was sad, he wrote his best poems. When he was happy, he didn’t write anything. This is true of me, where poems are concerned. When I am happy (or neither happy nor sad), I write essays, short stories, and novels. Poems—even happy ones—emerge from an accumulation of sadness.

J.O.: Can you describe the process of writing a poem? How do you know, for instance, when you have captured what you wanted to?

A.W.: The writing of my poetry is never consciously planned, although I become aware that there are certain emotions I would like to explore. Perhaps my unconscious begins working on poems from these emotions long before I am aware of it. I have learned to wait patiently (sometimes refusing good lines, images, when they come to me, for fear they are not lasting), until a poem is ready to present itself—all of itself, if possible. I sometimes feel the urge to write poems way in advance of ever sitting down to write. There is a definite restlessness, a kind of feverish excitement that is tinged with dread. The dread is because after writing each batch of poems I am always convinced that I will never write poems again. I become aware that I am controlled by them, not the other way around. I put off writing as long as I can. Then I lock myself in my study, write lines and lines and lines, then put them away, underneath other papers, without looking at them for a long time. I am afraid that if I read them too soon they will turn into trash; or worse, something so topical and transient as to have no meaning—not even to me—after a few weeks. (This is how my later poetry-writing differs from the way I wrote Once.) I also attempt, in this way, to guard against the human tendency to try to make poetry carry the weight of half-truths, of cleverness. I realize that while I am writing poetry, I am so high as to feel invisible, and in that condition it is possible to write anything.

J.O.: What determines your interests as a writer? Are there preoccupations you have which you are not conscious of until you begin writing?

A.W.: You ask about “preoccupations.” I am preoccupied with the spiritual survival, the survival whole, of my people. But beyond that, I am committed to exploring the oppressions, the insanities, the loyalties, and the triumphs of black women. In The Third Life of Grange Copeland , ostensibly about a man and his son, it is the women and how they are treated that colors everything. In my new book In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women, thirteen women—mad, raging, loving, resentful, hateful, strong, ugly, weak, pitiful, and magnificent—try to live with the loyalty to black men that characterizes all of their lives. For me, black women are the most fascinating creations in the world.

Next to them, I place the old people—male and female—who persist in their beauty in spite of everything. How do they do this, knowing what they do? Having lived what they have lived? It is a mystery, and so it lures me into their lives. My grandfather, at eighty-five, never been out of Georgia, looks at me with the glad eyes of a three-year-old. The pressures on his life have been unspeakable. How can he look at me in this way? “Your eyes are widely open flowers / Only their centers are darkly clenched / To conceal / Mysteries / That lure me to a keener blooming / Than I know / And promise a secret / I must have.” All of my “love poems” apply to old, young, man, woman, child, and growing things.

J.O.: Your novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, reaffirms an observation I have made about many novels: there is a pervasive optimism in these novels, an indomitable belief in the future and in man’s capacity for survival. I think that this is generally opposed to what one finds in the mainstream of American literature. One can cite Ahab, Gatsby, Jake Barnes, Young Goodman Brown.... You seem to be writing out of a vision which conflicts with that of the culture around you. What I may be pointing out is that you do not seem to see the profound evil present in much of American literature.

A.W.: It is possible that white male writers are more conscious of their own evil (which, after all, has been documented for several centuries—in words and in the ruin of the land, the earth) than black male writers, who, along with black and white women, have seen themselves as the recipients of that evil, and therefore on the side of Christ, of the oppressed, of the innocent.

The white women writers that I admire, Chopin, the Brontës, Simone de Beauvoir, and Doris Lessing, are well aware of their own oppression and search incessantly for a kind of salvation. Their characters can always envision a solution, an evolution to higher consciousness on the part of society, even when society itself cannot. Even when society is in the process of killing them for their vision. Generally, too, they are more tolerant of mystery than is Ahab, who wishes to dominate, rather than be on equal terms with the whale.

If there is one thing African Americans have retained of their African heritage, it is probably animism: a belief that makes it possible to view all creation as living, as being inhabited by spirit. This belief encourages knowledge perceived intuitively. It does not surprise me, personally, that scientists now are discovering that trees, plants, flowers, have feelings . . . emotions, that they shrink when yelled at; that they faint when an evil person is about who might hurt them.

One thing I try to have in my life and in my fiction is an awareness of and openness to mystery, which, to me, is deeper than any politics, race, or geographical location. In the poems I read, a sense of mystery, a deepening of it, is what I look for—for that is what I respond to. I have been influenced—especially in the poems in Once—by Zen epigrams and by Japanese haiku. I think my respect for short forms comes from this. I was delighted to learn that in three or four lines a poet can express mystery, evoke beauty and pleasure, paint a picture—and not dissect or analyze in any way. The insects, the fish, the birds, and the apple blossoms in haiku are still whole. They have not been turned into something else. They are allowed their own majesty, instead of being used to emphasize the majesty of people, usually the majesty of the poets writing.

dp n="67" folio="42" ?J.O.: A part of your vision—which is explored in your novel—is a belief in change, both personal and political. By showing the change in Grange Copeland you suggest the possibility of change in the political and social systems within which he lives.

A.W.: Yes. I believe in change: change personal, and change in society. I have experienced a revolution (unfinished without question, but one whose new order is everywhere on view) in the South. And I grew up—until I refused to go—in the Methodist Church, which taught me that Paul will sometimes change on the way to Damascus, and that Moses—that beloved old man—went through so many changes he made God mad. So Grange Copeland was expected to change. He was fortunate enough to be touched by love of something beyond himself. Brownfield did not change, because he was not prepared to give his life for anything, or to anything. He was the kind of man who could never understand Jesus (or Che or King or Malcolm or Medgar) except as the white man’s tool. He could find nothing of value within himself and he did not have the courage to imagine a life without the existence of white people to act as a foil. To become what he hated was his inevitable destiny.

A bit more about the “Southern Revolution.” When I left Eatonton, Georgia, to go off to Spelman College in Atlanta (where I stayed, uneasily, for two years), I deliberately sat in the front section of the Greyhound bus. A white woman complained to the driver. He—big and red and ugly—ordered me to move. I moved. But in those seconds of moving, everything changed. I was eager to bring an end to the South that permitted my humiliation. During my sophomore year I stood on the grass in front of Trevor-Arnett Library at Atlanta University and I listened to the young leaders of SNCC. John Lewis was there, and so was Julian Bond—thin, well starched and ironed in light-colored jeans, he looked (with his cropped hair that still tried to curl) like a poet (which he was). Everyone was beautiful, because everyone (and I think now of Ruby Doris Robinson, who since died) was conquering fear by holding the hands of the persons next to them. In those days, in Atlanta, springtime turned the air green. I’ve never known this to happen in any other place I’ve been—not even in Uganda, where green, on hills, plants, trees, begins to dominate the imagination. It was as if the air turned into a kind of water—and the short walk from Spelman to Morehouse was like walking through a green sea. Then, of course, the cherry trees—cut down, now, I think—that were...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- ALSO BY ALICE WALKER

- Acknowledgments

- CHRONOLOGY

- The World Has Changed

- Introduction

- 1 - Interview with John O’Brien from Interviews with Black Writers (1973)

- 2 - Interview with Claudia Tate from Black Women Writers at Work (1983)

- 3 - “Moving Towards Coexistence”: An Interview with Ellen Bring from The ...

- 4 - “Writing to Save My Life”: An Interview with Claudia Dreifus from The ...

- 5 - “Alice Walker’s Appeal”: An Interview with Paula Giddings from Essence (1992)

- 6 - “Giving Birth, Finding For : Where Our Books Come From”: Alice Walker, ...

- 7 - “The Richness of the Very Ordinary Stuff”: A Conversation with Jody Hoy (1994)

- 8 - “My Life as Myself”: A Conversation with Tami Simon from Sounds True (1995)

- 9 - A Conversation with Howard Zinn at City Arts & Lectures (1996)

- 10 - “The World Is Made of Stories”: A Conversation with Justine Toms and ...

- 11 - “On Finding Your Bliss”: Interview with Evelyn C. White from Ms. (1998)

- 12 - “On the Meaning of Suffering and the Mystery of Joy”: Alice Walker and ...

- 13 - “I Know What the Earth Says”: Interview with William R. Ferris from ...

- 14 - Alice Walker and Margo Jefferson: A Conversation from LIVE from the NYPL (2005)

- 15 - “Outlaw, Renegade, Rebel, Pagan”: Interview with Amy Goodman from ...

- 16 - Alice Walker on Fidel Castro with George Galloway from Fidel Castro ...

- 17 - A Conversation with Marianne Schnall from feminist.com (2006)

- 18 - A Conversation with David Swick from Shambhala Sun (2006)

- 19 - On Raising Chickens: A Conversation with Rudolph P. Byrd (2009)

- NOTES

- CONTRIBUTORS

- INDEX OF PEOPLE AND WORKS

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The World Has Changed by Alice Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.