![]()

Act 1

66-59 MILLION YEARS AGO

•

IN WHICH AMERICA IS CREATED AND UNDONE

![]()

ONE

GROUND ZERO

The death-dealing visitor appeared in the skies 65 million years ago above a planet that had long rested in contented stability. The era it terminated—the age of dinosaurs—had dawned following a crisis in life history some 180 million years earlier. The steady unfolding of evolutionary change in this tranquil world had seen the first birds, first mammals and first flowering plants come into existence. Thus, despite the fact that it was dominated by dinosaurs, the age was the nursery of our times.

At its dawn all the world's continents were joined into one vast landmass known as Pangaea, which was inhabited by many kinds of animals and plants. Pangaea was destined to divide into two super-continents, known as Laurasia and Gondwana, and by the end of the era these landmasses had begun to fragment, giving rise to the contemporary continents.

Continents are not born like people, for there is no day, century or even millennium that we can hail as a continental ‘birthday’. This is because continents are born of inexorable geological forces that move at glacial speed. They coalesce, break apart and re-collide, driven by great convection currents circulating in the Earth's mantle. Most of the existing continents were formed of fragmentation: Australia, Antarctica, South America and Africa all came into existence as a result of the break-up of the supercontinent Gondwana. North America, however, was created differently—it resulted from a victory of the forces of union.

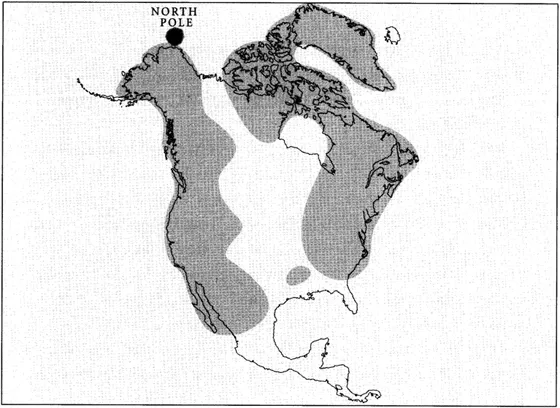

North America was born in the twilight moments of the age of dinosaurs, and at birth it was a very different place, for there was no Mississippi River, no Rocky Mountains and no Isthmus of Darien. Instead, a vast shallow seaway, dubbed by Canadian scientists the Bear- paw Sea, occupied its southern and central portions, dividing North America into separate eastern and western landmasses. The Bearpaw Sea had been in existence for at least 35 million years and had acted as a Zoogeographie barrier.1 During their long separate histories the two islands destined to form North America had become as different as Australia and South America are today. Some species did, however, manage to cross the Bearpaw, possibly by using volcanic islands (which would have been important breeding grounds for species such as the giant marine reptiles, seabirds and perhaps pterodactyls) as stepping stones. As the Bearpaw Sea narrowed such crossings became more frequent, heralding the amalgamation of the two island realms into a continental whole.

The landmass that constituted the eastern island of this proto-North America had long been geologically stable and bereft of mountain-building heat and energy. The Appalachian Mountains that were its backbone began to form over 450 million years ago and had already been eroded into a flat-topped cordillera by 230 million years ago. Zoogeographers can identify various animal groups that probably first evolved on this ancient island in the Mesozoic sea, among them the largest family of salamanders in the world, the Plethodontidae or lungless salamanders.2 By the end of the age of dinosaurs the east coast of this ancient land had been eroding and subsiding into the sea for tens of millions of years.

Throughout much of the Cretaceous period North America existed as two isolated islands, separated by the broad but shallow Bearpaw Sea.

America's western island was, in contrast, a geologically restless land that had been joined to Asia via the Beringian land bridge for hundreds of millions of years. Its fauna and flora were largely shared with Asia. Just before the asteroid struck, the Sierra Nevada had come into existence and was a high, jagged range of recently extinct volcanoes. Rivers draining eastward from their peaks meandered across a broad coastal plain towards the Bearpaw Sea. Looking from those high peaks to the west, one would have seen the Pacific Ocean, but the western coastline was then very different. Where beaches and headlands stand today there was nothing but water, for there was no Baja California (the peninsula was still stitched to Mexico proper) and parts of what are now coastal Oregon and Washington were islands positioned far out to sea. A portion of what is now coastal California was also islands, situated well south of its present location. Furthermore, most of Mexico was submerged under a shallow sea.

Long before the asteroid struck pressures had been building deep within the Earth's crust that would eventually thrust the Rocky Mountains high into the air, but for the present the movements caused by these pressures served only to narrow the inland seaway that divided America. By the end of the age of dinosaurs its southern section was still a shallow gulf, its mouth located near present-day Houston. In polar regions, however, the seaway changed into freshwater lakes and swamps, providing partial access across the newly unified continent.

Dramatic changes in the vegetation of North America had been occurring as the Bearpaw Sea narrowed. Earlier, great tropical conifers such as relatives of the monkey puzzle tree, which today have a primarily southern hemisphere distribution, had been dominant. At this time the pines of the boreal north, including the family to which the genus Pinus belongs, were yet to take on their modern form. Their ancestors were still growing as shrubs in ancient heath-like communities—pygmy plants revealing no signs of their greatness to come. Tens of millions of years would pass before they would come to resemble modern pines. The flowering plants likewise then lived as humble shrubs and twining plants in gaps in the canopy.

As the age of dinosaurs drew to a close many flowering plants began to grow larger and some, such as members of the magnolia family, would become the first flowering trees. Just two million years before the asteroid struck, these trees had formed a great belt of evergreen tropical forest that extended in a swath, south of 60 degrees latitude (the present latitude of Nunivak Island, Alaska), right across the continent's middle. This forest did not entirely replace the great conifers, however, for some were now gigantic trees, towering above the canopy of broad-leaved flowering plants. Growth rings are difficult to detect in the fossilised timber of these trees, which indicates an absence of seasons.

To understand the nature of that ancient forest it helps to walk the badlands along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. There, amid the grey, black and tan buttes of soft eroding rock that jut out throughout the valley, the Midland Coal Company found an entire ancient forest turned to coal, which they mined until the 1950s. Even where there are no seams of coal the rocks are packed with ancient plant remains. Leaves of exotic Asian species such as the ginkgo and the dawn redwood cram the sediments, alongside the tropical forms of the araucaria and palm. In one special layer the plant remains were not turned to coal, but were instead replaced with black silica. When freed by acid from the surrounding ironstone these 65 to 70-million-year-old fossils look like the most exquisite jewels—tiny branchlets, seeds and cones preserved in the finest glassy detail. To pick up a dusty rock packed with such fossils from among the sparse badlands shrubs struggling to survive is a strong reminder of just how much the world has changed since the demise of the dinosaurs.

As the continent was thus being born a bright, star-like object appeared in the sky. This was no guiding star but a stony, malevolent extraterrestrial visitor. The death-dealing lump of rock that shone so brightly was at least ten kilometres in diameter. That's a piece of celestial real estate two to three times the length of Australia's Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock), the largest monolith on our planet. We can imagine it silently approaching a steadily revolving Earth; a jagged lump of stone playing a game of Russian roulette with life's mothership. Perhaps it had missed narrowly on a billion earlier occasions, or perhaps it was on a new and deadly trajectory, pulled from its timeless round in the asteroid belt by the gravity of another passing heavenly body. Had we been perched on that lump of rock 65 million years ago, we would have watched the Earth grow ever larger as we descended upon it. It was not an equatorial aspect that we would have seen but a vision of the planet's nether regions, for the asteroid was approaching from the south. A verdant, glacier-free Australo-Antarctica would have first flashed past. Then a rotating Earth would have displayed a narrowed Atlantic Ocean to the crosshairs of our imaginary asteroidal sights. Above that expanse of water we might have calculated the chances of a splashdown in the sea. Today water covers about 70 per cent of the globe, but 65 million years ago it was even more expansive, covering 75 per cent of the Earth's surface.

As the asteroid came closer its path led it towards the mouth of a great gulf, the entry to the Bearpaw Sea. The equator was behind us now, the asteroid set on a course that, just slightly changed, could so easily have resulted in a near miss. But no, Ground Zero would be squarely in the mouth of that ancient American waterway. Today the site straddles the northern tip of Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula and its surrounding, tropical seas. Near its epicentre lies the town of Chicxulub Puerto, near Progreso, from which the impact site takes its name. When it hit, the rock released the equivalent of 100 million megatons of high explosive, about one hundred times the energy needed to create a global catastrophe, bringing the Mesozoic era—the age of dinosaurs—to a close.3

The Chicxulub Crater is lost to the world today. The massive scar, around 180 kilometres in diameter, is buried under a kilometre of limestone rock, deep below a region famous for its white sand beaches and its riot of tropical growth. The fact that the scar has been smothered by limestone, a rocky product of existence itself, and that a diverse albeit somewhat dry tropical forest forms a garnish on its surface, is eloquent of the victory that life has had over this alien death-dealer. But such a thing must have seemed barely possible at the time of impact, for then life came close to being extinguished entirely, at least in North America.

The sea into which the great lump of rock splashed down was about ten metres deep. I imagine it as being rather like the tropical seas of today, with their mixture of azures and luminous greens, and teeming with fish and other marine life. Only back then there were giant reptiles rather than whales and dolphins, and ammonites (like nautiluses) but no reefs of coral like today. Instead, giant clams (some a metre long and shaped like the horns of cattle, others jammed together in enormous colonies) took their place.

Until recently no one knew exactly what kind of extraterrestrial object had collided with the Earth on that day so long ago. Some championed a comet, others a meteorite. But on 19 November 1998, in an article in the journal Nature, Professor Frank Kyte of the University of California announced that he had found what might well be a piece of the object itself. It was a fluke discovery—a fragment of corroded rock no larger than a match-head recovered from a core taken kilometres deep in sediments underlying the central Pacific Ocean. The fact that a drill piece just a few centimetres across encountered this tiny extraterrestrial visitor buried deep beneath the ocean gives one pause to reflect upon chance as well as our present mastery of this planet.4

The miniature chunk, degraded as it is, still bore the distinctive chemical signature of a carbonaceous chrondrite—a stony meteorite. Such meteorites are rare, constituting just a few per cent of all that fall to Earth but, significantly, they appear to be common in the asteroid belt. The nemesis of the dinosaurs thus appears to have been an errant asteroid, possibly a fragment from a sister planet long since reduced to rubble by some mysterious power, or a fragment left over from the beginning of the solar system that somehow escaped incorporation into a larger heavenly body. Independent studies of the chromium preserved in ancient sediments the same age as that containing the fragment have since reinforced Kyte's findings, for researchers have discovered that they are rich in a kind of chromium similar to that found in carbonaceous chrondrites.5

This rock hit the Earth at a speed of at least twenty-five kilometres per second, the atmosphere providing little if any cushioning effect. It almost certainly disintegrated on impact, as stony meteorites are prone to do. Despite this, it opened a hole five kilometres deep in the Earth's crust, blasting thousands of times its original mass into the atmosphere and back into space, where some earthly fragments doubtless became heavenly wanderers themselves.

The great smoking pit left by the impact must have been an incomprehensible sight. How long, I wonder, did the ocean continue to pour into it? So big was the hole that one could not have seen from one side to the other, and so deep that no cliff on Earth today could produce such vertigo. The vast quantities of pulverised rock and blasted life it shot into the atmosphere must have turned the blue planet brown.

Geologists can pinpoint the moment the impact occurred worldwide by the presence of a layer of sediment rich in iridium. Iridium is largely absent from the Earth's crust but is abundant in asteroids and it seems that the disintegration of the carbonaceous chrondrite released enough iridium to act as a global calling card. The iridium layer also contains another indication of disaster—grains of sand known as ‘shocked quartz’. The name comes from changes in the crystal structure of quartz produced when intense shock waves pass through it. It develops striations that travel in more than one direction and can even recrystallise into new minerals as a result of the intense pressure of the shock. Alongside these ‘shocked’ sand grains are tiny glassy spheres, pieces of the Earth's crust that have been thrown high into the atmosphere, then melted to a glassy smoothness as they fell to ground.

This was an impact so intense it could send portions of the Earth spinning into space, coat the globe with iridium and, on the micro-scale, change the structure of grains of sand. How could such awesome forces have been generated, and what were the implications for Ground Zero America? If the location of the strike was unfortunate for North America, the angle of the blow was nothing short of catastrophic. Seismic studies of the crater indicate that the asteroid made a low swipe from the southeast that—like a golfer's chip shot—generated tens to hundreds of times more heat than a vertical strike would have done. It literally fried America, the heat generated by the impact reaching 1000 times that provided by the sun. And the result would have been particularly severe within 7000 kilometres of the impact point, an area that effectively covers the continent.6

The atmospheric shock wave must have flattened trees all over North America, creating great piles of timber. There is convincing evidence that the Earth's atmosphere was then about 10 per cent richer in oxygen than it is today. With oxygen levels at about 23 per cent this was a flammable world—when oxygen comprises 24 per cent of the atmosphere, even damp timber will burn. Not surprisingly, evidence has been discovered of vast forest fires following the impact, and a global soot layer has been identified. It appears that much of the northern hemisphere was carbonised by the impact.7

The celestial chip shot had other unfortunate consequences, for it took a huge divot of molten rock and debris and propelled it straight up the Bearpaw seaway. Evidence of the result is found in the distinctive sediments that formed as a result of the catastrophe. These rocks differ from similar-aged deposits elsewhere on Earth in that they have two distinct layers. The lower one is a chaotic mixture of materials and may represent part of the ‘divot’ dumped unceremoniously by the shock wave. The upper layer is better sorted and has thinner layers within it, as if it were laid down by water. Such rocks have been found all along the southern margin of North America, for example on the Brazos River, Texas and near Braggs, Alabama, as well as the Caribbean and Mexico. The exact nature of the upper layer is still debated, but many researchers postulate that they resulted from titanic tsunamis that raked the land a few hours after the asteroid hit.8

Scientists think that the sea along the southern coast of North America withdrew as it poured into the crater, only to return a few hours later as an enormous tsunami, or more likely a series of them. Were the waves a kilometre high ‘the largest in the history of the world’ as some claim?9 Whatever the case, I cannot imagine them as being anything but titanic, devastating all that remained standing in interior North America.

No humans have ever experienced anything comparable to the asteroid impact, but once—just once in written history—a faint echo of the great impact was directly experienced by a small section of humanity. On 27 August 1883 the island of Krakatoa, lying in the strait between Sumatra and Java, blew apart, releasing as much energy as 10,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs. A vast cloud of pulverised rock blocked out the sun for fifty-six hours. Villagers reported that the darkness was more profound than that of the blackest night, for it was palpable, like a blanket, and it cut off not only sight, but sound as well. In the terrible silence that reigned, they did not hear the explosion that 3000 kilometres away in central Australia was mistake...