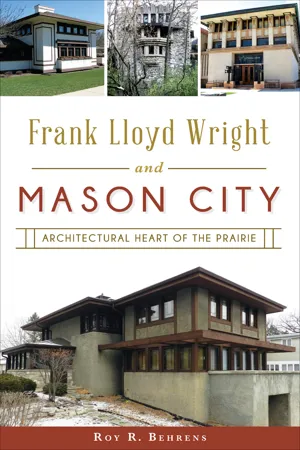

![]()

1

MASON CITY, KINDERGARTEN AND THE IMPERIAL HOTEL

On the first day of September 1923, an American businessman named Walter Scott Rooney (the father of CBS news commentator Andy Rooney) was in his room at the new Imperial Hotel in downtown Tokyo, Japan.15

The hotel had been designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and this was its formal opening day. At two minutes before noon, as Rooney was sitting at a table enjoying a cup of tea, the building suddenly started to shake so violently that the tea spilled out.

In the moments that followed, Tokyo was ripped apart by a massive earthquake, followed by aftershocks, fires and turbulent winds. It was one of the largest, most catastrophic earthquakes in modern history, resulting in as many as 150,000 deaths.

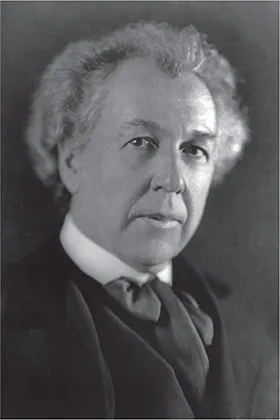

Photograph of architect Frank Lloyd Wright (circa 1926). Library of Congress (LOC) Prints and Photographs.

Reconstruction of the main lobby of Wright’s Imperial Hotel (circa 2015) at Meiji-mura in Inuyama, Japan. Photograph by Bariston (Wikimedia Commons).

Wright was in Chicago that day. Eighteen months earlier, he had been in Tokyo, when the city was struck by a previous earthquake (the largest in thirty years at the time). The building was “in convulsions,” Wright wrote, yet he offered reassurances that the structure was purposely built to withstand any earthquake of any magnitude.16

Now, on the day of the building’s premiere, Wright’s credibility was at stake. Had the Imperial Hotel survived? Was it still standing? There were erroneous rumors that the structure had collapsed. But communications had been blocked, and for a number of days, Wright “walked the floor, inconsolable,” awaiting a factual update.17

In time, confirmation came that the Imperial Hotel was among the few buildings still standing. Not only had it survived the earthquake, but it had even been used as a refuge for displaced victims. Still, news reports continued to claim that it had been substantially damaged. The truth was somewhere in between.

TIES TO MASON CITY

In an effort to quell the rumors, Wright reached out to a California-based public relations expert named Merle Armitage, who was also an acquaintance. Armitage was “an old friend” of the architect’s son, Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. (known professionally as Lloyd Wright), who was working at the time as a Hollywood film set designer and residential architect.18

Armitage was a book designer and arts impresario, the manager of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium and would also later become the art director of Look magazine. His promotional efforts on Wright’s behalf were presumably effective, and today it is widely conceded that Wright’s Imperial Hotel (although damaged) was largely resistant to earthquakes.

Whenever this curious story is told, it is rarely mentioned that Wright and Armitage had something else in common: both men had important ties to a small city in north-central Iowa. It was the county seat of Cerro Gordo County called Mason City.

Mason City was, in fact, Merle Armitage’s birthplace. Born in 1893 on a farm southeast of the city, he had grown up in that community, then resettled with his parents when his father (one of the earliest livestock farmers to raise corn-fed beef cattle) moved his business interests to Lawrence, Kansas, and after that to Texas.

The Armitage family was no longer living in Mason City when, in 1908, in the course of several visits to the town, Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned by two local attorneys, James E.E. Markley and James E. Blythe (both on the board of directors of a major city bank), to design a multipurpose building that would include a bank, an adjoining hotel, their own law offices and rentable retail spaces as well. Located beside a downtown park, the hotel was named the Park Inn, while the bank was officially known as the City National Bank.19

STOCKMAN HOUSE

On an early visit to Mason City, Wright was introduced to Dr. George and Eleanor (Chaffin) Stockman, a local physician and his wife who were Markley’s friends and neighbors.

Eleanor Stockman was an impassioned advocate of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her sister, Fannie Chaffin, was a longtime secretary to that organization’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt. The latter had grown up in nearby Charles City, Iowa, and had also recently served as a teacher and the first superintendent of schools in Mason City.20

Two views of the George C. Stockman House in Mason City, Iowa, in 2007. Photographs by Pamela V. White (Wikimedia Commons).

The Stockmans approached Wright about designing a two-story, four-bedroom home, both compact and affordable. In response, Wright proposed that he rework an existing plan that he had already published in the Ladies’ Home Journal called “A Fireproof House for $5,000.”21

Prior to that, as early as 1903, one of Wright’s associates, Walter Burley Griffin (while employed in Wright’s studio), had used a similar building plan for the Robert Lamp House in Madison, Wisconsin. A shared characteristic of these and other comparable homes is their “open floor plan” in which there are no dividing walls between the living room and dining room. As a result, these critical zones of activity blend into an L-shape, with a family hearth in the center.22

The Stockman House (as it is now commonly known) was completed in 1908. By 1924, Dr. Stockman had retired, and both he and his wife were failing in health. After Eleanor Stockman died that year, the house was sold. In subsequent years, it passed from owner to owner until 1987. Increasingly in disrepair and threatened with demolition (to make way for a church parking lot), it was heroically rescued by a civic-minded community group, which in 1989 moved it to a setting four blocks down the street, raised funds to restore it and opened it as a museum in 1992. By that remarkable effort, a modest yet pivotal landmark was saved for future generations.23

Through continued efforts by the River City Society for Historic Preservation, adjacent property was acquired just north of the Stockman House, and in 2011, the Robert E. McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center was completed. Designed by Iowa architect Robert Broshar in a manner that pays homage to both Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Burley Griffin, it functions year-round as a museum and gift shop facility that offers instructional lectures, collectibles and self-guided tours of all architectural highlights in Mason City.24

SUCCESS AND SCANDAL

In planning the City National Bank and Park Inn, Wright made use of what he had learned from previous building projects. Likewise, while working on these Mason City commissions, he gained in ways that strengthened his subsequent efforts, notably the Midway Gardens (in Chicago) and the Imperial Hotel (in Tokyo). Wright’s Mason City projects (the Stockman House and the City National Bank and Park Inn) were completed between 1908 and 1910.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs.

His Mason City clients were delighted with Wright’s accomplishments, and there were rumors of future commissions. But before any of those could be realized, he was publicly disgraced by an outrageous personal scandal, in the course of which he abandoned his wife and six children and went to Europe for a year with the wife of one of his clients.25

As it turned out, Wright had been in love for several years with an Oak Park neighbor named Martha (“Mamah”) Borthwick Cheney (pronounced “MAY-mah CHEE-ny”). Originally from Boone, Iowa, she herself was the mother of two young children.26

It was largely because of this scandal (gossip-laced reports of which were front-page stories in the news) that, as Katherine Rodeghier recently wrote in the Chicago Tribune, Wright “wasn’t exactly run out of town [Mason City]; he was asked never to return.”27 While some uncertainty remains, it is usually assumed that Wright never again set foot in Mason City. While he undoubtedly had access to photographs of the finished buildings, it may be that he never saw the City National Bank and Park Inn in their completed physical state.

In October 1909, Wright and Mamah Borthwick Cheney hurriedly left for Europe.28 During their year-long absence, the actual construction of the Mason City bank and inn was managed by a Wright associate, Chicago architect William Drummond, who in addition agreed to take on the design of another Mason City residence: the Curtis Yelland House at 7 River Heights Drive.29

Following Wright’s return from Europe in October 1910, he was commissioned to design the Midway Gardens, an elaborate concert garden and restaurant on Chicago’s South Side.30

Most likely, Wright and Merle Armitage first became acquainted in 1915. The latter was in Chicago that year, working as a manager and publicity agent for stage and concert performers. The great Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova was featured at the Midway Gardens several times that summer, in addition to other now legendary performers, including the Ballet Russes (Russian Ballet), operatic tenor Enrico Caruso and others.31

It was during this time that Wright’s career as an architect was substantially reestablished when he was commissioned to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

WRIGHT AND KINDERGARTEN

When and how did Frank Lloyd Wright, an up-and-coming architect from the burgeoning Windy City, become linked historically to a city as small and seemingly out of the way as Mason City, Iowa? One answer—believe it or not—is kindergarten.

Kindergarten in this case does not refer to preschool as we know it now but to the original kindergarten (or “children’s garden”) of German educator Friedrich Froebel that began in Europe in the 1830s. Froebel’s kindergarten was not a literal garden (although, at times, its pupils did raise plants) but rather a radical new approach to early childhood teaching.32

Froebel challenged the customary practice of treating children as if they were adults in miniature, to be molded by rigid restr...