![]()

PART I

THE LIFE OF LIVIA

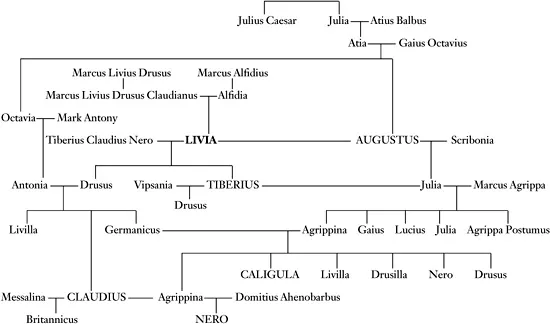

Stemma 1. Livia’s significant family connections

![]()

1

FAMILY BACKGROUND

The expulsion of the last hated king from Rome, an event dated traditionally to 510 BC, ushered in a republican form of government that was to endure for more than four centuries and which was regarded by later Romans, especially those from the elite levels of society, with pride and an often naive nostalgia. At the outset, Roman society was characterised by a fundamental division between the patricians, who held a virtual monopoly over the organs of power, and the plebeians, who were essentially excluded from the process. Although the power and privileges of the patricians were eroded during the first two centuries of the republic, it is a mistake to think that the system became open and democratic in the modern sense. The removal of the barriers facing ambitious plebeians resulted in a modification of the aristocracy, not its abolition. The chief magistracies became the almost exclusive reserve of a small number of families, whether plebeian or patrician, and the historical record is dominated by a handful of prestigious families, such as the Cornelii or the Julii, who succeeded in keeping a tight grip on the key offices (the system is summarised in appendix 2). Anyone who broke into the closed system and reached the highest office, the consulship, despite lacking a consular ancestor was such a novelty that he was known as a “new man” (novus homo). The popular assemblies, through which legislation had to be enacted and which might seem on the surface to have offered the masses scope to exercise an influence, in fact did little to upset the balance, because a complex voting procedure gave a distinct advantage to the wealthy.

The importance of family background as a virtual prerequisite to success in Roman society can not be overstated, and, as Tacitus acknowledges, few could have rivalled Livia’s claim to family distinction.1 On her father’s side, she was descended by blood from one of the proudest and highest-flying of all the great Roman families, the Claudian. According to legend, the family’s founder was Clausus, who supposedly helped Aeneas when the Trojan hero sought to establish himself in Italy.2 In the historical record, the Claudii were in reality immigrants who did well, and their association with the city might be said to begin with the migration to Rome of the Sabine Attus Clausus and all his dependants in 503 BC. Co-opted into the patricians, Attus claimed the first Claudian consulship in 495. Subsequently his descendants would expect, almost as an entitlement, a consulship each generation. Suetonius records that they eventually boasted twenty-eight consulships, five dictatorships, seven censorships, six triumphs, and two ovations.3 Their family history is a veritable parade of some of the giants of Rome’s past. In 451, as a member of the Decemvirate (Commission of Ten Men), Appius Claudius was instrumental in giving Rome its first written legal code. One of his descendants was among the most distinguished and venerated figures of the old republic, and probably the first figure of Roman history to emerge as a clear and distinct personality—Appius Claudius Caecus, consul in 307 and 296. Even when aged and blind he was still consulted as an elder statesman, as on the celebrated occasion when in about 280 BC he addressed the Roman Senate, the senior deliberative and legislative body, made up of men who had held the important magistracies. In a speech passed down through the generations and still used as a school text when Livia came into the world, he persuaded his fellow senators to reject as dishonourable the peace terms offered by King Pyrrhus. Claudius Caudex led the Roman forces into Sicily at the outbreak of the First Punic War against Carthage in 264, and during the Second War, Gaius Claudius Nero defeated Hasdrubal in 207 as he made his way to join his brother Hannibal. This pattern of high office continued to the end of the republic.4

Like their modern counterparts, the important Roman families were often made up of more than one branch. Appius’ two sons, Tiberius Claudius Nero and Publius Claudius Pulcher, were the founders of the two main subdivisions of the patrician Claudians, the Claudii Nerones and the Claudii Pulchri. Livia could claim descent from one and would marry into the other.5 The Nerones apparently soon faded from view. Tiberius Claudius Nero was the last Nero-nian consul, in 202, until Livia’s son, the future emperor Tiberius, was elected to the office in 13 BC. The Pulchri, on the other hand, went from strength to strength, and carved out a preeminent role in Roman political life.6

Amidst the paragons of public service and duty, however, tradition also ascribed to the patrician Claudii a motley collection of rogues and eccentrics, linked to the white sheep of the family by common possession of the notorious Claudian pride. Tacitus could speak of one of their descendants as marked vetere ac insita Claudiae familiae superbia (by the old inborn arrogance of the Claudian family); Livy speaks of a family that is superbissima and crudelissima (excessively haughty and excessively cruel) towards the plebeians, a sentiment echoed by Suetonius’ description of them as violentos ac contumaces (violent and arrogant). Whether this reputation was deserved, or resulted from a hostile historical tradition, is perhaps not particularly relevant in the present context, because it was the reputation that would be bequeathed to Livia and the line of emperors that followed her.7 Tradition has grafted onto the worthy if dull achievements of Appius Claudius, the decemvir and lawgiver, a luridly sinister role of would-be tyrant and insatiable defiler of women, the most noteworthy being Verginia, slain by her own father to save her from Appius’ lust—and, of course, to save her father loss of face. Publius Claudius Pulcher, consul in 249, had contempt not only for man but also for the gods. He suffered a major defeat in a naval battle against the Carthaginians at Drepana, losing 93 of his 123 ships. His defeat was blamed by some writers on his outrageous behaviour when the auspices hinted strongly that his enterprise was headed for disaster. The sacred chickens refused to eat. He ignored the sign and, according to some, in a fit of pique dumped them into the sea, announcing, “If they won’t eat, let them drink.”8 The stories seem endless. Appius Claudius Pulcher, father-in-law of Tiberius Gracchus, provoked the Salassi of Gaul into a costly war during his consulship in 143 and suffered a defeat and the loss of five thousand men. In a later engagement he redressed the balance by killing five thousand of the enemy. He assumed arrogantly that he was entitled to a triumph, the grand procession through Rome granted victorious generals who fulfilled a specific set of conditions, and he requested the necessary funds from the Senate. When his request was refused, he simply went ahead and staged the triumph at his own expense.9 Suetonius tells a story, otherwise unknown and whose historicity cannot be determined, of a Claudius Drusus who set up his own crowned statue at Forum Appi and tried to use his clients to take over Italy.10

Tradition was even-handed in one respect, for the Claudian women were painted as no less arrogant than the males. Claudia, for instance, was the daughter of the distinguished statesman Appius Claudius Caecus and the sister of the Claudius Pulcher who lost his ships to the Carthaginians. When Claudia’s carriage was blocked by a crowd of pedestrians, she lost her temper and prayed, loudly of course, for her brother to come back to life to lose another fleet of Romans. She was fined for her outburst. Another Claudia, the daughter of the pseudotriumphator Appius, joined him in his chariot during the triumphal parade. There was a danger that he would be hauled out, but she, as a Vestal Virgin with sacrosanctity, would be able to protect him from the intervention of the tribune. Arguably the most notorious Claudian woman of all time was still alive during Livia’s youth. Clodia Metelli was famed for her profligacy and political power. Her numerous lovers almost certainly included the poet Catullus (he gave her the pseudonym Lesbia) and her brother, the demagogue Publius Clodius. She was berated by the orator Cicero for bringing shame on her distinguished Claudian ancestors.11

One of the descendants of this celebrated if eccentric family was Livia’s father, Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus. We have no knowledge of Marcus’ biological parents, though he is described as a Claudius Pulcher by Suetonius (the only one actually to claim this), and his family seems to have had a connection with Pisaurum. This old colony, at the mouth of the Pisaurus in Umbria, was apparently a depressing place. Catullus, writing in the 50s, calls it moribunda, and Cicero describes it as a hotbed of discontent. Thus when Cicero at one point mockingly calls Marcus a Pisaurensis, it was clearly intended as a slur.12 But Pisauran or not, Marcus was still a Claudian. Livia’s mother Alfidia came from far less distinguished stock. She was the daughter of a Marcus Alfidius, a man of municipal rather than senatorial origins, and she may have attracted an eligible aristocrat like Marcus Livius Drusus through her family wealth.13 She seems to have come from Fundi, a pleasant town on the Appian Way, in the coastal area of Latium near the Campanian border. Fundi was noted for its fine wine but was generally been viewed as a place for escape—many Romans had country villas in the vicinity. Suetonius twice alludes to Livia’s connection to the town. He reports that some (wrongly) believed that Livia’s son, the emperor Tiberius, had been born at Fundi because it was his grandmother’s hometown. In another context, to illustrate one of the many vagaries of her great-grandson Caligula, Suetonius cites a letter to the Senate in which the emperor alleged that Livia had been of low birth because her maternal grandfather had been merely a decurion (town official) of Fundi. Caligula, of course, was much given to wicked jokes at his family’s expense, and his charge should perhaps not be taken too seriously (see appendix 3).14

Livia’s descent on her father’s side from one of Rome’s oldest and most prestigious families would have conferred enormous status on her. That status would have been enhanced by another link, no less important politically and originating in this case through adoption. An admirer of Livia’s, the contemporary historian Valerius Maximus, describing the feud of Claudius Nero and Livius Salinator, censors of 204 BC, remarks that if they had realised that Livia’s son would be descended from their blood, they would have ceased to be rivals. With this eloquent display of sycophancy Valerius testifies to the “dual line” of Livia. Her name, Livia Drusilla (see appendix 4), in itself gives no hint of a Claudian connection. Rather it reflects her family connection with a man who earned a secure if controversial place in Roman history. The Livii seem to have been an eminent Latin clan who received Roman citizenship in 338 following the Latin revolt.15 Their most famous member emerged in the aftermath of the disintegration of the social order that followed the adoption by the Senate of violent emergency measures to counter the land resettlement schemes proposed in 133 BC by Tiberius Gracchus and subsequently by his brother Gaius. The republic was not to recover from the severe blows it suffered during this crisis, which brought martyrs’ deaths to the Gracchi. The crisis also brought to the fore a distinction between the optimates, who represented the old senatorial class, with its traditional claim over the higher magistracies, and the populares, who sought to promote the initiative of the tribunes and the consuls to introduce legislation free of the heavy hand of the Senate.

Gaius Gracchus had included among his proposals a measure to extend the franchise to Rome’s Latin allies, and a limited franchise to the Italians. In 91 BC the issue of the Italian franchise returned with a vengeance, and it was during this critical phase that Marcus Livius Drusus came into prominence, when as tribune of the plebeians he took up a number of causes, including agrarian reform and, most notably, a move to enfranchise all Italians living south of the river Po. He somehow succeeded in firing the imagination of the Italian communities to see him as the man to champion their rights. At the same time, however, he encountered considerable opposition in Rome. There were outbreaks of disorder, and Drusus was murdered by an unknown assailant. His death fomented widespread resentment and was the decisive element leading to the outbreak of armed revolt in the Social War. What he had sought through political action eventually came about through conflict, and by 89 the allies had been absorbed into the Roman state. Livia’s family connection with the champion of the rights of the Italians must be seen as a major asset, especially in the later stages of the civil war that would end the republic, when warring factions competed for broad support.

As Drusus breathed his last he reputedly declared to his weeping entourage, ecquandone similem mei civem habebit res public?—when will the state have another citizen like me?16 What precise qualities he had in mind in his final moments are not known, but his family, through adoption rather than bloodline, was to produce in Livia someone whose fame would far eclipse the tribune’s. Livia’s father, Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, was born a Claudius, as his name indicates, but was adopted into the Livian family. In the Roman fashion he assumed the nomen of the adopting gens, the Livii, and appended an adjectival form of his original gens, the Claudii.17 With adoption he would have been expected to assume the praenomen of his adoptive father; the fact that he was a Marcus, combined with the absence of any prominent Livian other than the famous tribune with the cognomen Drusus, strongly suggests that this Drusus was the adoptive father.18 From her link with the tribune Livia acquired her cognomen, Drusilla. It also gave her family the name Drusus, which some of her descendants opted to bear as a praenomen.

If Marcus was the adopted son of the tribune, he would have found himself in an advantageous position. On the death of his new father he could have inherited all or part of his estate. Diodorus Siculus called the tribune Marcus Livius Drusus the richest man in Rome, and his observation seems to be supported by other sources.19 This wealth would have given an important boost to his son’s career. Moreover, as we have seen, Marcus’ inherited wealth might have been amplified by money from his wife’s family. The Alfidii would have considered a lavish dowry a small price to pay for a connection with such a socially prominent Roman, a man described by Velleius Paterculus as nobilissimus. 20

Livia’s father steps onto the stage of Roman history in 59 BC, during a period of great political tension. The end of the struggle over the franchise in Italy did not mean an end to overseas conflicts. In 83 the general Sulla, flushed with his victories over king Mithridates, who ruled in the Black Sea area, returned to Italy at the head of his troops and after a period of turmoil and conflict was appointed dictator with special powers. He made it his mission to restore the supremacy of the Senate, retiring in 79. The Senate squandered their advantage. They offended the military commander Pompey, who, having undertaken a successful campaign in the East, on his return found the senators unwilling to ratify the measures he had undertaken. The Senate also offended the wealthy financier Crassus by restricting his financial dealings in Asia. The same body further alienated a new rising star, Julius Caesar, denying him the prospect of the consulship on his return from Spain in 60. In that year Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus found common cause and formed an compact often referred to casually by modern scholar...