- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

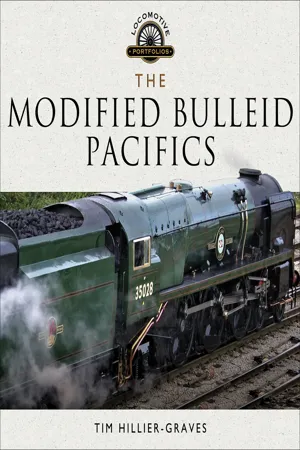

The Modified Bulleid Pacifics

About this book

This British Railways history recounts the life of a controversial steam engine and its miraculous transformation at the hands of a brilliant engineer.

As Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Southern Railway, Oliver Bulleid designed what were perhaps the most controversial steam locomotives ever built in Britain: the Pacifics. Loved and loathed in equal measure, the debate over their strengths and weaknesses took on a new dimension when British Railways decided to modify them in the 1950s.

When noted engineer Ron Jarvis was charged with improving on Bulleid's designs, he displayed a master's touch, saving the best of Bulleid's work while incorporating other established design principles. What emerged was described by Bert Spencer, Gresley's talented assistant, as taking 'a swan and creating a soaring eagle.'

This book explores all the elements of the lives of these Pacifics and their two designers. It draws on previously unpublished material to describe their gradual evolution, which didn't start or finish with the 1950s major rebuilding program.

As Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Southern Railway, Oliver Bulleid designed what were perhaps the most controversial steam locomotives ever built in Britain: the Pacifics. Loved and loathed in equal measure, the debate over their strengths and weaknesses took on a new dimension when British Railways decided to modify them in the 1950s.

When noted engineer Ron Jarvis was charged with improving on Bulleid's designs, he displayed a master's touch, saving the best of Bulleid's work while incorporating other established design principles. What emerged was described by Bert Spencer, Gresley's talented assistant, as taking 'a swan and creating a soaring eagle.'

This book explores all the elements of the lives of these Pacifics and their two designers. It draws on previously unpublished material to describe their gradual evolution, which didn't start or finish with the 1950s major rebuilding program.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

INFLUENCES, OPPORTUNITIES AND IDEAS

Oliver Bulleid and Ron Jarvis were from different eras. One was the product of a Victorian world, with all its self-belief, certainties and divisions, the other of an ever changing post-Great War Britain, where extreme sacrifice had driven the need for social reform and a better existence for all. Their lives and careers were shaped by the two eras in which they grew up, although a love of engineering helped them cross many boundaries that time and attitudes imposed.

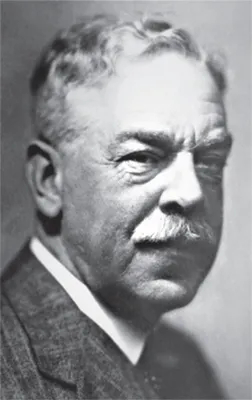

Oliver Bulleid at the time of his promotion to CME (ES/RH).

Both were exceptionally gifted engineers who played significant roles in the development of many locomotives, but one type stands out from the others, the iconic Southern Region Pacifics. Without Bulleid, they probably would not have been built and without Jarvis they might have been consigned prematurely to the scrapyard by British Railways, as time revealed serious flaws in their design. In so doing, he turned a concept full of promise into a masterpiece of engineering, but, despite this, they will always be known as Bulleid’s Pacifics, whilst Jarvis remains hidden in the shadows, barely remembered. Yet of the two, Jarvis may have been the more talented engineer, with an eye for the practical that meant he took fewer flights of the fancy down doubtful paths or cul-de-sacs, probably more conservative in outlook than Bulleid, but more successful because of it.

The timing of their careers also deeply affected the roles they played and the opportunities they could exploit. Bulleid rose to prominence in 1937 when he was appointed to be the Southern Railway’s Chief Mechanical Engineer. But with another war brewing in Europe, he had little time to develop his ideas as a period of austerity beckoned, so his concepts for the new engines of which he dreamed seemed likely to die stillborn.

During the 1930s, as one of Nigel Gresley’s assistants on the LNER, he had participated in many great schemes, but could not lead in this golden age of development, as steam locomotive design leapt forward with ever higher speeds, streamlining and headline-grabbing glamour. Now his own chance seemed thwarted by the vagaries of history and the march of dictators. Even when the war ended, his opportunities would still be restricted by a changing world and nationalisation. Who knows what he might have achieved if his tenure had begun earlier and he had enjoyed the freedom open to others. As it was, by grit and determination, and despite the war, he pushed back the boundaries of what was possible and created his Pacifics.

Jarvis, then a young engineer with the LMS, also served in these pre-war years, but at a much more junior level. The greatest and most productive period of his career lay in the future, beyond the war when investment and innovation offered the talented an opportunity to experiment and explore. He would play a part in the design of new steam engines for BR and be allowed to see beyond the end of that world into new forms of traction. There would be the limitations imposed by a nationalised industry, with its short-sighted and fickle political masters, but this didn’t seem to inhibit Jarvis, who was capable of working within such a system. Bulleid railed at the restrictions and would fall foul of a regime that had to be negotiated with guile and stealth if success were to be achieved. And here his Victorian self-belief and certainties would let him down. He didn’t learn to play a new game and found himself isolated, sidelined and then eased out.

The world had been so different when he was a child growing to maturity, although his earliest days were coloured by a tragedy that shaped his life. Born in 1882, the eldest of three children, to British parents who had emigrated to New Zealand in 1878, the loss of his father in 1889 drove his mother back to the UK where her family could offer support. Faced with the difficult problem of accommodating three children at her widowed mother’s home in Llanfyllin, it was decided to despatch young Oliver to live part time with his uncle, aunt and two cousins in Accrington. One wonders where life might have taken him if he had remained in a largely non-industrial New Zealand and not moved to a heavily industrialised Great Britain. He may have found his way into engineering, but it is probable that he would not have achieved the success he did and play such a significant part in railway history along the way.

Having begun his education in New Zealand he went on to attend school in Accrington, before moving to the Spa College at the Bridge of Allan for two years. There then followed a four-year period at the Municipal Technical School in Accrington before being apprenticed to the Great Northern Railway at Doncaster in 1901. Here he passed under the control of the company’s Locomotive, Carriage and Wagon Superintendent, Henry Ivatt, a man who would have the most profound influence on his life at work and at home; in 1908 he would marry his youngest daughter Marjorie. But before this happened he was eager to better himself educationally and boost his knowledge and improve career opportunities. So during his apprenticeship, and after it, he attended evening classes in Doncaster, then three nights a week at Sheffield University before moving to Leeds University.

John Click, who would later work for Bulleid at Brighton and became a good friend, recorded many of their conversations. Click, who began work as a premium apprentice draughtsman when the heavy and light Pacifics were being designed, recalled that:

‘I found it hard to picture OVB as an apprentice for by nature he was an academic with a very enquiring mind constantly asking ‘‘why’’ and never accepting anything because it was ‘‘the way we do it’’. One senses that he asked too many questions, yet never gave up. He read a lot, made visits whenever he could, including to Crewe Works in 1902 where Francis Webb still had a year to go.’

Nigel Gresley, Bulleid’s mentor and guide (LNER PR/RH).

He also described the effect of losing a friend at this time had on the young Bulleid:

‘OVB shared digs with a fellow apprentice called Talbot, who was to lose his life in the Grantham accident of 1906. Though still an apprentice he was firing an Ivatt Large Atlantic, in place of the regular man, a practice not unusual at that time. I think this affected Bulleid deeply and accounted for his view of footplatemen and the perils they could face. As a result I don’t think he ever experienced the delight of firing and driving a locomotive, even his own. He did ride on the footplate for many important and exciting events, though, and was quite fearless of high speed, but these were the exceptions.

‘He had the rare ability of being able to take a ride on the footplate and to step off at the end just as clean and as immaculately attired as when he got on. I could never imagine him lending a hand when things were going wrong. It certainly wasn’t snobbishness, but a certain aloofness born of shyness.’

In 1910, when seeking membership of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, his application recorded details of the tasks he undertook as an apprentice:

‘January 1901 to January 1905 – in the GNR Works at Doncaster: passing through turneries, fitting, erecting shops and drawing office, then into Running Shed doing shed fitting and obtained running experience.’

He also recorded being ‘privately coached in Steam Mechanics and Structures’, then achieved ‘matric at London University’. All this is confirmed and countersigned by Ivatt, who had clearly been impressed by the young man and so had taken a very close interest in his development. Armed with this backing, a good education and great personal skills, Bulleid began to shine. Immediately on qualifying, he was appointed ‘Assistant to the Outdoor Superintendent at Doncaster in charge of experiments with petrol motor driven coaches’ swiftly followed by ‘ placed in charge of various work in connection with out-stations’. Then for a year he became ‘Assistant to the Works Manager in charge of Shop Costs’ before seeking employment at ‘the Freinville shops (Paris), French Westinghouse Co, as Engineer of Test’. Such a move spoke of his ambition as did a move to the Board of Trade as Mechanical Engineer for exhibitions in 1910. Interestingly, this suggests that he didn’t see railway engineering as the sole route his career should follow, but the appointment only lasted for a year and then folded up leaving him in the lurch.

Now married with a young daughter, he returned to Doncaster and with his father-in-law’s help was appointed Personal Assistant to Nigel Gresley, then replacing a retiring Ivatt as Locomotive, Carriage and Wagon Superintendent. He started work in January 1912 and the most important phase of his career and development began, shaped by his own skills and ambition, but heavily sponsored and directed by his new leader for the next 25 years.

Gresley was a very perceptive man, as well as being an outstanding engineer. But more than that he understood human nature, ambition and the need for new challenges and personal development. He also understood team dynamics and good business management. He was, by any standards, an exceptional leader and a perfect chief and guide for Bulleid at this stage in his career. There is also evidence that he was a calming influence on the younger man, who was beginning to show a headstrong attitude that didn’t always sit comfortably with his fellow workers. Dynamism matched with a fertile imagination and great intelligence can often have this effect and there is no doubt that he was imbued with these qualities. Ernest Cox, who was also a locomotive engineer of great skill and knew Bulleid well from the 1930s, described his character in his book Locomotive Panorama in quite frank terms:

‘To an extent unknown on other railways, he had been a supreme autocrat within his own department and had been able to impose his will upon management … An individualist of the deepest dye, he had no sympathy at all with the painstaking improvement of the breed, but wished with brilliant and dramatic improvisations to solve the remaining problems of steam by quite other means. To him novelty was everything. If it would not work then this could not be the fault of the idea itself, but only of the incapacity of those who tried to carry out or use it. The cross which he had to bear was that his developments with conventional practice were successful, sometimes brilliant, whereas his exercises in the bizarre, which he loved dearly as his brain children, often failed.’

But Cox also saw another side of Bulleid, the tough but charming negotiator:

‘He knew in advance that we were bound to introduce practice which was alien to his thought processes and to divert the activities of his assistants from frantically trying to solve the impossible into more normal channels. I remember my first official contact with him … His charm and tact eased a confrontation which could have been very difficult … He did not disguise his attitude however, and expressed in an extremely gentlemanly way, that he had cast his pearls before swine.’

In reality, the world of locomotive development, though close to his heart, was probably too restricted a field of exploration for his agile, questioning, scientific mind. So the attitude Cox describes may have been born of frustration at the limitations imposed by his chosen career. In truth, his skills and intelligence were probably better suited to a broader area of science than the railways could offer. But luckily, he had Gresley to offer advice, lead him and keep his imagination in check. Later, when he became the Southern Railway’s CME, he would be in sole charge with only a rather ponderous, remote General Manager and Board of Directors offering any sort of control over his work. And this freedom lent itself very well to the development of his Pacifics. Nationalisation, when it came in 1948, proved a bitter pill for Bulleid to swallow because it slowly stripped him of autonomy and freedom of action.

But in 1912, these events were far in the future and for the moment, under Gresley’s guiding hand, the young engineer gradually flexed his engineering and leadership muscles on a range of projects. Armed with such strong skills, he fitted perfectly into the role of ‘trouble shooter’. He moved around the organisation assessing engineering and management problems, then recommending practical solutions. Occasionally his forthright attitude rubbed others up the wrong way causing friction. But as his analysis always seemed right he received Gresley’s backing, even acquiescence at times when his advice picked holes in the Superintendent’s own solutions. Then war came and Bulleid chose to ignore the reserved occupation status of many jobs on the railway to join up. A commission was offered and in January 1915 he crossed to France to join the Army Service Corps later that year.

No one is left unaffecte...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Influences, Opportunities and Ideas

- Chapter 2 Bulleid’s Developing Fleet

- Chapter 3 Endeavours Fade to be Renewed

- Chapter 4 Spring and Port Wine

- Chapter 5 A Last Flurry

- Chapter 6 In Loco Parentis

- Appendix 1 Bulleid’s Merchant Navy – Evolution, Design and Construction

- Appendix 2 A Light Pacific Emerges – A Pictorial Study

- Appendix 3 Interim Modifications

- Appendix 4 The Rebuilding Programme

- Appendix 5 Bulleid Comments on Rebuilding

- Appendix 6 9 July 1967

- Appendix 7 Condemned, Scrapped, Survived

- Appendix 8 The Life of One Locomotive

- References and Sources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Modified Bulleid Pacifics by Tim Hillier-Graves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Modern British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.