![]()

THE TRANSITION YEARS OF THE 1870s

A new era in the history of the GNR was heralded by the departure of the three characters who had most influenced the development of the company since the securing of the Act of 1846. The most notable was the Chairman, Edmund Denison, who had become involved in the London and York railway proposals back in 1844, fought numerous battles with rivals and had finally been forced to resign due to poor health in December 1864. Working closely with him was Seymour Clarke, General Manager from 1850 to 1870. Along with Archibald Sturrock, holding the post of Locomotive Engineer from 1850 to 1866, these two men had created the GNR’s reputation for its customer service and the speed of its trains. It could be said that these three characters had nurtured the GNR through its 1850s childhood and into its adolescence in the 1860s, leaving others to take the company into its early adulthood of the 1870s.

The GNR main line through Hatfield station as it appeared after the repositioning of the down platform (on the right) in 1864. The canopy might have been erected at the same time but certainly no later than about 1875, when this photograph was taken. The earlier preference for building canopies that covered both the platform and its adjacent track can be seen in the background. (T.W. Latchmore, Hitchin/Author’s collection)

Safety

By the end of the 1860s all GNR stations were protected by semaphore signals, but the interlocking of signals with the operation of points was not to be found everywhere on the network. Neither was block working. Interlocking and block working were only installed where thought necessary due to local conditions. At the beginning of the 1870s, however, the Board of Trade through the Railway Inspectorate was pressuring companies to adopt both, consistently, over all lines. The threat of legislation to enforce this persuaded the GNR – and other companies – to change their approach to signalling. From just sixty-four route miles (103km) controlled by the block system in 1869, by 1876 the GNR had almost 350 route miles (563.3km) so protected, and by the end of this period, the GNR had erected hundreds of new signalboxes, all with interlocking lever frames. The majority of these structures survived in use for over 100 years. With decorative barge boards on their gable ends, they were the first characteristically GNR structures, displaying what would be later termed a ‘corporate identity’. The architectural features that elevated these new signalboxes from the simple huts and cabins that had preceded them only a few years earlier, were overt indicators that the GNR was taking safety more seriously and was proud to display this. Consequently, when an accident at Abbotts Ripton happened on the night of 21 January 1876, GNR management must have felt dismay after such a short period in which so much had been invested in moving from the ad hoc signalling arrangements of the 1860s to what they believed was a new comprehensive and safe system of traffic management.

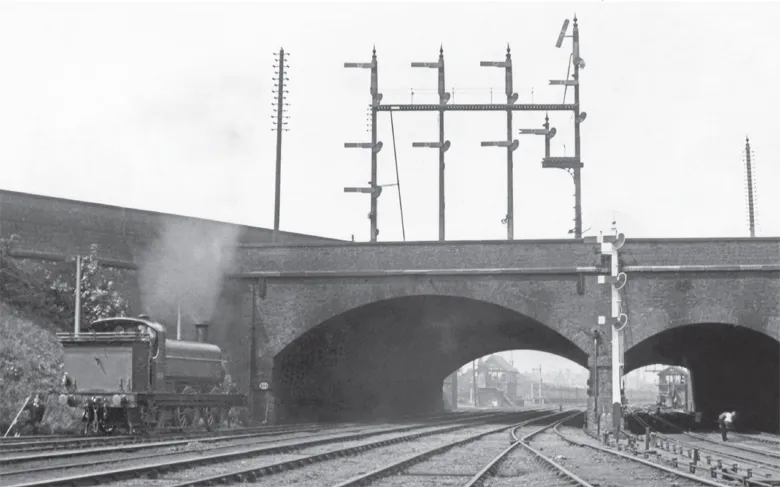

Balby Bridge just south of Doncaster station with its four post signal gantry. The structure must have been erected before the middle of the 1870s because the tops of all four posts show they originally had semaphore arms pivoted in slots. The arms were subsequently replaced with ‘somersault’ semaphores but the spectacle glasses and lamps remained where first fitted at the base of the slots. All the arms below the walkway were later additions (as was the distant signal beneath the arm in the ‘off’ position on the right post). (Official photograph/Author’s collection)

The signalbox brought into use at Rossington station in March 1876. At least six other signalboxes on the main line between Grantham and Doncaster were built to this same design in this period, all fitted with interlocking lever frames and equipped with the electrical equipment for working the absolute block system. (Commercial postcard./Author’s collection)

This signalbox at South Elmsall on the West Riding & Grimsby Railway jointly owned by the GNR and MS&LR was one of many brick and timber signalboxes brought into use in the 1870s all over the GNR network. (Author’s collection)

It is well known that the cause of the accident was the failure of the levers in the signalboxes in the area to move the semaphore arms from the ‘all clear’ position to ‘danger’ because they had become frozen in their signal post slots by compacted snow. This misled the drivers of an up coal train and two expresses into believing the line was clear. Having passed Holme signalbox where it should have stopped, a coal train was being shunted into a lay-by siding at Abbotts Ripton when it was struck, first by an up express and then a north-bound express, all running under false clear signals. Fourteen passengers were killed and over fifty injured.

In the Board of Trade report following the accident, one of the recommendations was that signals protecting the entry to block sections should normally indicate ‘danger’ (or ‘blocked’) and not ‘all clear’. But even this change did not prevent another accident on the GNR two days before Christmas 1876. A goods train was being shunted across the main line at Arlesey Sidings where there was also a small station (opened in 1860 and then rebuilt to become Three Counties station in 1886). The manoeuvre had resulted in some of the wagons becoming derailed on the main line. The home and distant signals were set to danger but because the shunting was taking place beyond (in advance of) the home signal, the line between Arlesey Sidings and Cadwell to the south was clear according to the regulations. A Manchester express entered the section and all would have been well if the driver had responded to Arlesey’s distant signal at danger. Unfortunately, he did not and the train also ran on past the home signal at danger, its progress only halted by hitting the derailed wagons. Both driver and firemen were killed, as were three passengers in the train, thirty being injured.

A photograph taken shortly after a memorial was erected at Abbotts Ripton following the accident there in January 1876. Other signalboxes known to have had the same design of windows and decorative barge boards were erected on the main line at Arlesey, Biggleswade, Sandy, Tempsford, Huntingdon and Holme between 1874 and 1876. All but Abbotts Ripton, Biggleswade North, Sandy North, and Huntingdon North remained in use for a hundred years. (Ernest Whitney, Huntingdon/Author’s collection)

After the accidents the GNR changed its design of semaphore, adopting one that eliminated the possibility of the arm sticking in the clear position. This ‘somersault’ signal very soon became a characteristic feature all over the network. Two other vital, but not so visible, changes were also made to block working procedures and adopted by other companies as well. The first was that lines between signalboxes were assumed to be ‘blocked’ whether or not there was a train travelling between them, and the second was the requirement that a specified distance beyond the home signal had to be unobstructed before a train could be allowed into the section. This distance beyond the home signal became known variously as the ‘clearing point’, ‘fouling point’ or ‘overlap’.

The main line near Essendine as originally laid out in 1851–2 with just two tracks. This late Victorian photograph was taken to illustrate the use of slag ballast but the distant signal is worthy of note. On the up line in this area, with its gradient falling towards Peterborough, the positioning of distant signals was very important. When the re-signalling of the 1870s had been completed, most were over 1,000 yards (914.4m) from the signalboxes that worked them. (Author’s collection)

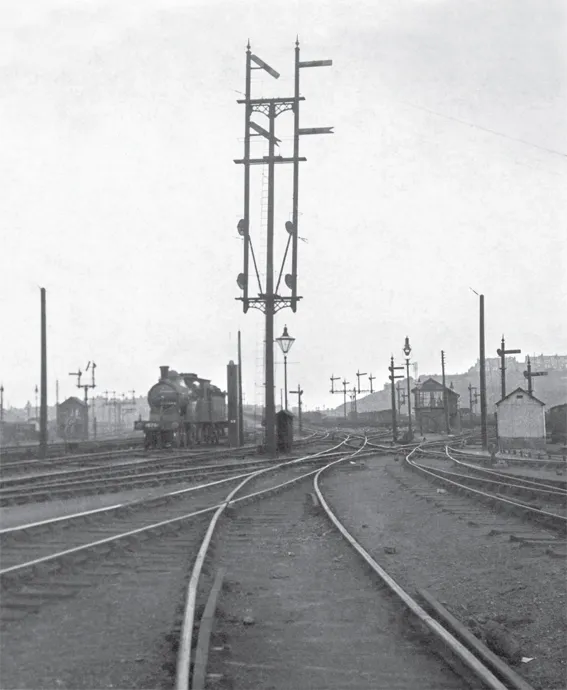

As the GNR ran fast passenger trains it believed drivers should be given the earliest indication of the state of the line in front of them. Consequently, tall signal posts and brackets were erected in many locations along the main line, such as this one just to the north of Hornsey station fitted with somersault semaphores. (12 June 1900 Locomotive Publishing Co./Author’s collection)

Beautifully decorated but with no brakes! 0-4-2 No. 70 was originally built as a 2-2-2 by Hawthorn & Co. in 1850 and rebuilt in May 1870. Posed here at Hitchin a few years later it was subsequently fitted with Smith’s simple vacuum brake, and then automatic brakes, and was not withdrawn until January 1901. (Author’s collection)

The 1876 accidents had also occurred at a time when the question of how best to stop a train in an emergency was being discussed. The decade had begun with passenger trains run with several brake vans, a driver sounding his whistle if he wanted the guards to apply their brakes to slow or stop the train. There were brakes on engine tenders but not on the locomotive itself, and the principle that all the carriages of a train should have brakes – referred to as ‘continuous brakes’ – had not been established at this time. However, growing public concern about railway accidents had led to the setting up of a Royal Commission in 1874, and in the following year trials were organised just south-west of Newark on the MR where a number of different braking systems were fitted onto ten different trains belonging to seven different railway companies. These were run up and down at various speeds, the distances covered and the times taken to stop being carefully measured. Amongst the British designs the equipment of two American inventors were on show: the GNR train fitted with a brake devised by J.Y. Smith and one of the MR trains fitted with another designed by George Westinghouse. The principal difference between the two systems was that although both were ‘continuous’, Westinghouse’s automatically applied the brakes on all the train even if it became divided or the equipment failed. At the time, although superior in this respect over Smith’s equipment, Westinghouse was still making modifications to his design and its apparent complexity convinced Stirling that it would need constant attention if it was to work reliably in everyday service. Consequently, Westinghouse’s overtures to GNR management were unsuccessful.

The accident at Abbotts Ripton took place only six months after the Newark Trials and very quickly Smith’s equipment was fitted to a number of GNR trains to test it under normal, main line running conditions. At the end of the year, Westinghouse made another appeal to the company to trial his improved automatic apparatus, but once again it met with a lukewarm response from Stirling. By the end of 1877 the trials with Smith’s equipment led to a definite policy of fitting all GNR engines and trains with that form of continuous but non-automatic vacuum brake.

London suburban traffic growth

By the mid-1860s the GNR was witnessing the first stages of a new phenomenon that was later to be called ‘commuting’. New housing was spreading ever northwar...