![]()

PART 1

WIMBLEDON

1860-1889

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION AT WIMBLEDON 1860-1889

Opening

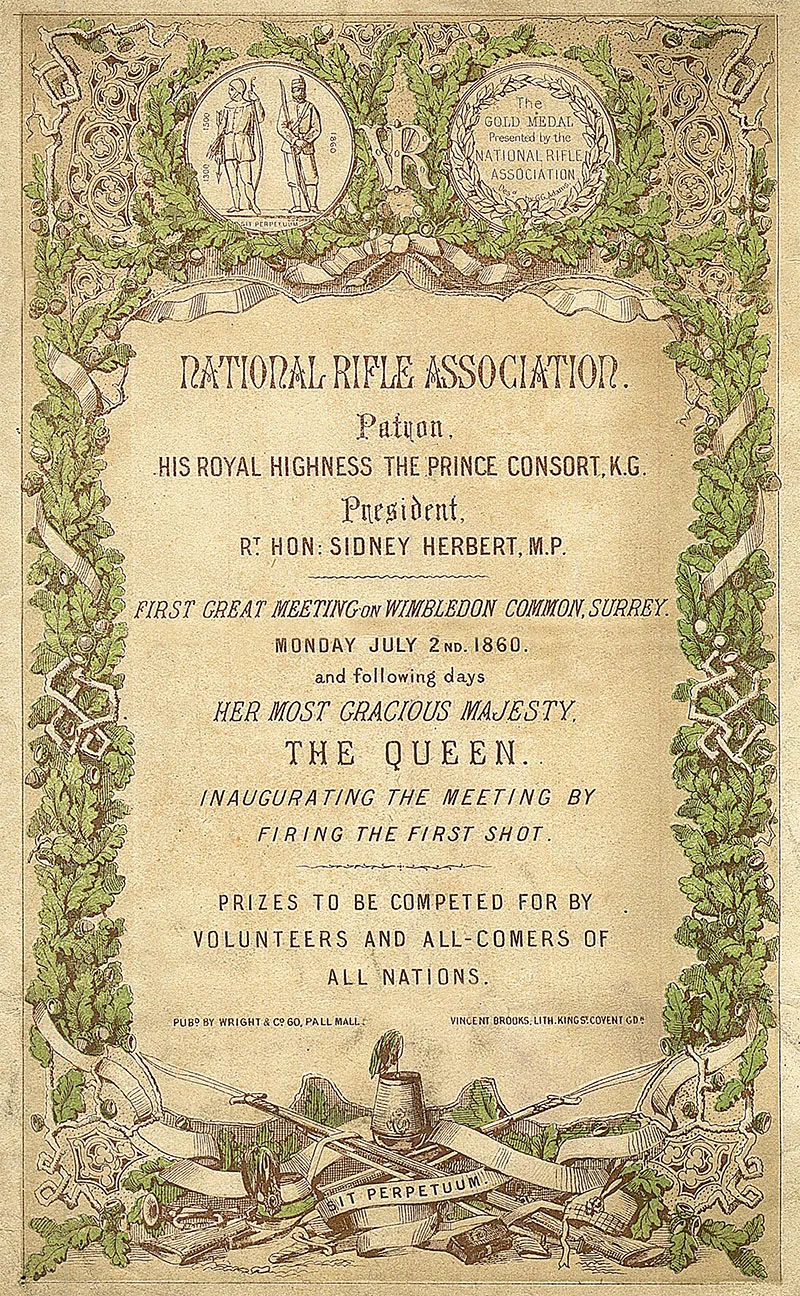

2 July 1860 had been fixed as the date for opening the first Meeting on Wimbledon Common with the Queen signifying her intention of inaugurating it in person by firing the first shot. Estimates for erecting the butts (£622) and the laying out of the enclosure (£250) were based on the hard, dry conditions existing on the Common at the time with the Government promising the loan of tents, mantlets (iron shelters for markers) and other necessary accoutrements. However, the rain then started to fall and did not finally let up until the day of the opening of the Meeting thus turning much of the Common into marsh with parts under water:

The front cover of the first Meeting Programme in I860. It was not until 1863 that the small but comprehensive pocket book, which became the famous ‘bible’, was first issued.

‘Nothing could look more hopeless, and the Council were obliged to issue orders from day to day for works to be done and preparations to be made which were never contemplated, and for which it was necessarily impossible to obtain estimates or enter into contracts. The Common had to be drained and ditches opened, roads had to be made, many hundred yards of planking for roadway had to be laid down; and large sums had to be expended in providing additional tents and accommodation for the protection of those who might be expected to be present at the inauguration; thus the estimated outlay has been more than doubled, as will be seen on reference to the printed statement of Accounts. Whilst referring to the preparation of the ground, the Council cannot omit recording their grateful sense of the services rendered by Colonel Bewes, by whom the butts were admirably laid out, and who for many weeks was constantly on the ground; and they would likewise acknowledge the efficient manner in which the butts were erected and the drainage and other works performed by Mr. Scott, who was engaged almost night and day in superintending the various operations up to the very hour of Her Majesty’s arrival. But notwithstanding the zeal and energy displayed by them, as well as by many other members of the Council and other gentlemen, the inclemency of the weather, and the difficulty of procuring labour, caused so many delays that at the last the Council were obliged to apply for fatigue parties of the Guards, and for some Sailors from Woolwich Dockyard. This aid was readily granted, and it was mainly owing to their exertions and the heartiness with which they worked, that everything was in readiness for Her Majesty’s reception at the opening of the Meeting.’

In recognition of the assistance given by the Swiss Tir Fédéral in setting up the Association one hundred and fifty riflemen from Switzerland paraded at the opening ceremony.

‘The Queen arrived about three o’clock and was received by the Premier, Lord Palmerston; the Secretary of State for War, Mr. Sidney Herbert; Lord Elcho, the great officers of State, and commanding officers of a large number of units of the Volunteer Force.

A guard of honour was mounted by the competitors, and with them were associated a hundred and fifty Swiss riflemen, the best shots of their respective societies or clubs, who had come over to take part in the first English national shoot. The Swiss wore no uniform beyond the badge or ribbon of their society, and they marched on the ground preceded by the flag of the Swiss Confederation. The Common was thronged with Volunteers in the varied uniforms of the numerous recently raised Corps. ’In such a young force,’ it was recorded in a contemporary account, ’it is not to be wondered at that the civilian was more apparent than the soldier,’ and the prints of the period show ’the curled whisker, the shaven upper lip, the long and aristocratically dressed locks of hair, and the shirt collar of the civilian, worn in conjunction with the military uniform. The uniforms also were more picturesque than soldierly, there being a general tendency to wear skirts to the tunic, nearly as long as those of a French vivandiere.’

After addresses had been presented to Her Majesty and the Prince Consort, the Royal party proceeded to the Pavilion, where Mr. Whitworth had, by means of a mechanical rest, fixed the rifle with which the Queen was to fire the first shot, the distance being 400 yards. A silken cord attached to the trigger was handed to Her Majesty by Mr. Whitworth, and the rifle having been fired by a sharp pull, it was found that so accurately had the rifle been adjusted that the bullet had struck the target within a quarter of an inch of the centre. A duplicate of the gold medal of the Association was then presented to the Queen by Lord Elcho, the chairman of the Council, while a salvo of artillery announced the opening of the meeting.’

The first Queen’s Prize was won by Private Edward Ross of the 7th North Yorkshire Volunteer Rifle Corps using a .451 Whitworth Rifle, with Lord Fielding of the 4th Flintshire Rifle Volunteers as ’runner-up.’ The prize-giving was held, on the Monday following the meeting, at the Crystal Palace (a practice which continued until 1864), and a crowd of twenty thousand assembled there to watch the distribution of the prizes by the Under-Secretary of State for War, Earl de Grey and Ripon, Sydney Herbert not being available. Chambers Magazine for 4 August carried a vivid eye witness description of the Meeting including the conclusion of the Queen’s Prize Competition in which Edward Ross finally triumphed over Lord Fielding.

Roger Fenton’s Photograph of ‘Her Majesty firing the First Shot’ at Wimbledon on the 2nd July 1860. The target is mounted on the left Butt of Number 1 Pair seen in the distance. (Roger Fenton - Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016)

‘The Queens Target’. The ‘first shot’ mark of the bullet fired by the Queen from the Whitworth Rifle. (Roger Fenton - Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016)

‘..............Passing through the entrance, where we paid one shilling, we found ourselves on the common - a wide heath, with patches of furze, and a fringe of tents. The eye took in the arrangements at a glance. Within the fringe of tents, which contained mainly refreshments, were a row of others in pairs, about a hundred yards apart, opposite and corresponding to pairs of butts 500 yards off. These were mounds of earth, some 15 feet high, and 30 feet wide. Beyond them was a still more distant line, nearly a mile off. In front of each stood the targets - plates of iron about half an inch thick, and six feet square, white-washed, with a black centre two feet in diameter. The furthest were so distant that the centre was just visible as a little black dot not much bigger than that of an ‘i.’

The Plan of the first Meeting held in 1860 showing the Queen’s Shooting Tent and the route of her Inspection Drive.

The tents from which the firing was going on were surrounded by crowds of people, who were kept from interfering with the shooters by a rope passed round a ring of stakes driven into the ground. The firing-tents to the right were occupied by the candidates for the Queen’s Prize of £250; those on the left were hard at work at ‘Aunt Sally.’ We visited these first. ‘Aunt Sally’ is adapted from the popular venture of that name at fairs and races. You pay a shilling for your shot, and the receipts are divided at the close of the day among those who hit the centre. I walked up to the tent opposite the third pair of butts; a crowd of gallant volunteers were waiting for their turn to shoot. The tent from which they fired in rotation was about eight feet wide, open before and behind. At the entrance, a man sat with pen, ink, and paper, ready to receive the moneys, and put down the names of those who hit the centre. Some twenty men were standing in single file, treading close on each other’s heels, and shuffling forward as the turn of the leading man came to fire; after which he moved off to the right, round the tent, reloaded, and took his place again in the line - like the processions in the smaller theatres. You might fire in any position. This liberty was freely used. Some stood; some knelt in the approved Hythe posture; others sat down, and gathered up their knees as if they were going to take their place in a circle of ‘Hunt the Slipper;’ others lay flat down upon their stomachs. The mistakes made were occasionally odd enough - ’Hollo! sir, you have forgotten to cock your rifle.’ ‘You have not put up your sight.’ ‘That is the wrong butt you are aiming at.’ One fat fellow sat down with a jolt and fired right up into the air!

Close beside each target was a bullet-proof iron shed, shaped like the body of a Hansom cab off its wheels: in this the marker sat, and signalled the result of each shot. A dark-blue flag shewed that the centre was hit; a white one, that the white part of the target had been struck; a red, waved close to the ground that the ball had fallen short. Armed with a race–glass, lent to me by one of the bystanders, I sat down on the grass at the entrance of the tent, and watched the shooting. The target, I have said was 500 yards off, and the centre two feet in diameter. No one was allowed to fire from a rest. This, then, was no child’s play, though many of those present joined in it with great merriment. The party who were firing belonged to a genuine London corps; many of them, till within the last few months, never had a rifle in their hands. The shooting however, was remarkably good. One smart young fellow was telling me how he knew nothing whatever about shooting until lately. When his turn came, he laid himself flat down on the ground, and quietly drove his bullet right into the centre –that is,he would have hit a man more than a quarter of a mile off. I stood by the tent for some time; again and again the distant flag was waved, shewing that the target had been struck; and this was the skill of men who hitherto had spent their lives behind the counter or at the desk. Think of that, ye sneering martinets and swaggering French colonels!

Here were thorough-bred Cockneys, poking fun at one another, but all the while making practice that would rival or even beat the famous Chasseurs de Vincennes, without seeming to think they were doing anything out of the way. A soldier alone, who stood by me, expressed any surprise.

Presently the order came to cease firing; and the markers, waving large red flags to indicate danger, came out of their holes, and went to dinner. Most of the spectators turned into a huge refreshment marquee, furnished by Strange, the caterer at the Crystal Palace. All tastes were suited; you could dine at any figure at well-ordered tables, or be happy on the grass with a slice of bread and cheese and a pot of porter. During the armistice, I walked up to the butts. For many yards in front of them the ground was covered with flakes of lead, the bullets that struck the iron having been, not flattened - that is too gentle a word - but actually splashed about. The targets were spotted all over with hits. Those untrained, inexperienced Londoners would have utterly cut up a body of horse or foot half a mile off!

When the firing began again, I went to see the conclusion of the contest for the Queen’s Prize - the highest honour of the week. The competitors had already been shooting at the 800 and 900 yard ranges; and when I walked up, a party of the Scots Fusilier Guards; in undress, were fixing up the tent to fire from at the final distance of 1000 yard. The target was also in this case white, with a centre two feet in diameter. It looked hopelessly distant. Imagine yourself standing at the Oxford Street circus, and expected to hit a tea-tray in Tottenham Court Road. There was quite a purple haze, that made the butt look like a distant hill, the target shewing like a white cottage at its foot with one small window.

Thousands of spectators had now assembled to watch the progress, or rather final struggle, of the match. The signal-flags were so distant, that many would not trust their naked eyes, but used a telescope.

In a very short time, the strife became exceedingly interesting. Mr. Ross and another gentleman were ahead of the rest, and equal. It was Mr. Ross’s turn. He knelt down, aimed deliberately, and pulled the trigger. Alas! his rifle was only at half-cock. This threw him out for a minute. Several voices sympathetically enough, said: ‘Ah, now he will miss.’ A shade of nervousness crossed his mind. His close competitor, strung up to the tightest strain of excitement, lay down flat upon the grass, and hid his face. Ross, having now cocked his rifle, missed as was predicted. The other gentleman picked himself up from the ground, and came forward. See! he kneels down, steadies himself upon his heel, and puts his rifle to his shoulder. No -not yet - something dazzles him. He takes it down for a moment, and passes his hand over his eyes. Another aim - crack! Yes - up goes the white flag; the target is hit - he is one ahead. Now, Mr. Ross, this is the crisis of your fame: miss, and you lose the prize; hit the centre, and you win - that will count two, and leave you victor by one point. It is a trying moment. The little dot on the white target seems to move further off; you can barely see it; but to hit it, with that small candle-end of lead you have just pushed into your rifle, shade of Robin Hood, behold! Now for nerves of steel, and a pulseless heart. All hold their breath. The marker’s ...