![]()

1. GAZING INTO THE ABYSS

Samuel Alexander (SA): Rupert, I would like to invite you into a space of uncompromised honesty. Let us engage each other in conversation, not primarily as scholars wanting to defend a theory, or as politicians seeking to win votes or advance a public policy agenda, or even as activists fighting for a cause, but instead, just as human beings trying to understand, as clearly as possible, our situation and condition at this turbulent moment in history.

When I look at the world today, I see the vast majority of academics, scientists, activists, and politicians ‘self-censoring’ their own work and ideas, in order to share views that are socially, politically, or even personally palatable. There are times, of course—often there are times—when we must be pragmatic in our modes of communication, and shape the expression of our ideas in ways that are psychologically digestible, compassionate, or even crafted to be attractive to an intended audience. But the more we do that, the more constrained we are from saying what we really think; the less able we are to look unflinchingly at the state of things and describe what we see, no matter what we find. If we never find ourselves in spaces of unconstrained openness, we might not even know what we really think, hiding truths even from ourselves.

It seems to me that one of the first principles of intellectual integrity is not to hide from truths, however ugly or challenging they may be. Yet there are truths today which I feel many people are choosing to ignore, not because they do not see them or understand them, but because they do not want to see or understand them. Truth, as any philosopher knows, is a contested term. But perhaps in what is increasingly called a ‘post-truth’ age, time is ripe to reclaim this nebulous notion, to try to pin it down, not in theory but in practice. That is to say, I am inviting you, Rupert, to practise truthfulness with me, to share thoughts on what we really think, and to do so, as far as possible, without filtering our perspectives to make them appear anything other than what they are. This may require some bravery, of course, because if thou gaze long into an abyss, as Nietzsche once said, the abyss may also gaze into thee. Have we the courage? Will our readers have the courage to stay with us on this perilous and uncertain journey?

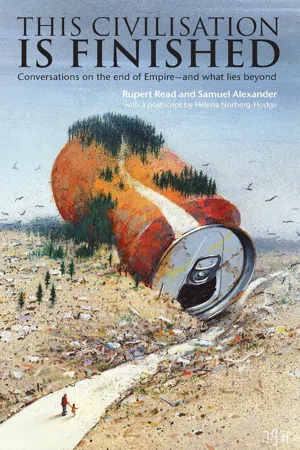

My invitation to you is not, of course, arbitrary. It seems to me that you are amongst a very small group of thinkers today who have already started the process of speaking ‘without filters’. I’ve seen you deliver lectures to your students saying things that most academics would not dare even to think, let alone say out loud in public. I’ve read articles of yours that manifest the uncompromised honesty that I hope will inform, perhaps even inspire, this dialogue. One of the articles to which I refer, and which now entitles this book, is called ‘This Civilisation is Finished.’1 Let that bold and unsettling statement initiate our conversation. No doubt it will require some unpacking. What did you mean when you declared that this civilisation is finished?

Rupert Read (RR): Thanks Sam. It is a privilege, in at least two ways, to be able to conduct this dialogue with you. First, it’s a privilege to be in dialogue on this vital matter with you, whose work on degrowth and voluntary simplicity is, in my opinion, simply the best there is. But I also mean that it’s a privilege, a wonderful luxury, to be able to have this conversation at all, because it is quite possible that in a generation’s time, or possibly much less than that even, such conversations will be an unaffordable luxury.

It is quite possible that, although we are living at a time that is already nightmarish for many humans in many ways (let alone for non-human animals), we will come to look back on these times, if we are alive to look back on them at all, as extraordinarily privileged. Right now people such as you and me don’t have to spend much of our time scrabbling for food and water or looking over our shoulders worrying about being killed. So we have a responsibility to make the most of this privilege.

What I’ve just expressed will strike some readers as exaggerated for effect. It is not. It is simply an attempt to level with everyone; to take up your invitation, Sam, and join you in a space of uncompromised honesty. Environmentalists are often accused of being doom-mongers. I think that the accusation is largely false, because I think that almost all environmentalists incline in fact to a Pollyanna-ish stance of undue optimism. This might prompt an accusation of me being a fear-monger or alarmist. I’m not an alarmist. I’m raising the alarm. When there’s a fire raging—as is the case right now, as I write, across the UK and across the world including in forests that are our planetary lungs—then that’s what one needs to do. Raise the alarm. This elementary distinction—between being an alarmist and justifiably raising the alarm—is exactly the distinction that Winston Churchill drew, under similarly challenging (though actually less dangerous) conditions, in the 1930s.

If people are feeling paralysed right now, I think it is probably because they are stuck between false hopes. On the one hand, there is the delusive lure of optimism, the hope that there will be a techno-fix that will defuse the climate emergency while life more or less goes on as usual. This is, I believe, in a desperately-dangerous way keeping us from facing up to climate reality. On the other hand, there are dark fears that people mostly don’t voice and don’t confront. My message, far from being paralysing, is liberating. One is liberated from the illusory comfort—that deep down most of us already know is illusory—of eco-complacency. One is able at last to look one’s fears full in the face. One is able at last to see the things that the other half didn’t want to see. And then to be freer of constraint in how one acts.

One of the ideas in the work of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein that most deeply inspires me is that the really difficult problems in philosophy have nothing to do with cleverness or intellectual dexterity. What’s really difficult, rather, is to be willing to see or understand what one doesn’t want to. After years of denial, and years of desperate hope, I finally reached a point where it was no longer possible for me to not see and understand the fatality that is almost surely upon us.

I have come to the conclusion in the last few years that this civilisation is going down. It will not last. It cannot, because it shows almost no sign of taking the extreme climate crisis—let alone the broader ecological crisis—for what it is: a long global emergency, an existential threat. This industrial-growthist civilisation will not achieve the Paris climate accord goals;2 and that means that we will most likely see 3–4 degrees of global over-heat at a minimum, and that is not compatible with civilisation as we know it.

The stakes of course are very, very high, because the climate crisis puts the whole of what we know as civilisation at risk. By ‘this civilisation’ I mean the hegemonic civilisation of globalised capitalism—sometimes called ‘Empire’—which today governs the vast majority of human life on Earth. Only some indigenous civilisations/societies and some peasant cultures lie outside it (although every day the integration deepens and expands). Even those societies and cultures may well be dragged down by Empire, as it fails, if it fells the very global ecosystem that is mother to us all. What I am saying, then, is that this civilisation will be transformed.3 As I see things, there are three broad possible futures that lie ahead:

(1) This civilisation could collapse utterly and terminally, as a result of climatic instability (leading for instance to catastrophic food shortages as a probable mechanism of collapse), or possibly sooner than that, through nuclear war, pandemic, or financial collapse leading to mass civil breakdown. Any of these are likely to be precipitated in part by ecological/climate instability, as Darfur and Syria were. Or

(2) This civilisation (we) will manage to seed a future successor-civilisation(s), as this one collapses. Or

(3) This civilisation will somehow manage to transform itself deliberately, radically and rapidly, in an unprecedented manner, in time to avert collapse.4

The third option is by far the least likely, though the most desirable, simply because either of the other options will involve vast suffering and death on an unprecedented scale. In the case of (1), we are talking the extinction or near-extinction of humanity. In the case of (2) we are talking at minimum multiple megadeaths.

The second option is very difficult to envisage clearly, but is, I now believe, very likely. One of the reasons I have wanted to have this dialogue with you, Sam, is so that we can talk about how we can prepare the way for it. I think that there has been criminally little of that, to date. Virtually everyone in the broader environmental movement has been fixated on the third option, unwilling to consider anything less. I feel strongly now that that stance is no longer viable. And, encouragingly, I am not quite alone in that belief.5

The first option might soon be as likely as the second. It leaves little to talk about.6

Any of these three options will involve a transformation of such extreme magnitude that what emerges will no longer in any meaningful sense be this civilisation: the change will be the kind of extreme conceptual and existential magnitude that Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher of ‘paradigm-shifts’, calls ‘revolutionary’. Thus, one way or another, this civilisation is finished. It may well run in the air, suspended over the edge of a cliff, for a while longer. But it will then either crash to complete chaos and catastrophe (Option 1); or seed something radically different from itself from within its dying body (Option 2); or somehow get back to safety on the cliff-edge (Option 3). Managing to do that miraculous thing would involve such extraordinary and utterly unprecedented change, that what came back to safety would still no longer in any meaningful sense be this civilisation.7

That, in short, is what I mean by saying that this civilisation is finished.

![]()

2. CLIMATE CHAOS: BLACK SWAN OR WHITE SWAN?

SA: The notion of a ‘black swan’ event was introduced into the cultural lexicon by Nassim Taleb to signify a radically unexpected and improbable event that has profound consequences. Something that would lead to the end of civilisation as we know it would presumably be unexpected—a black swan—because otherwise people would have done something about it. Presumably. Yet you call dangerous anthropogenic climate change a ‘white swan’. What are you getting at?

RR: Much of my work in recent years concerns the impact of improbable events that can be ‘determinative’, wiping out the effects of decades of normality or ‘progress’. For instance, there is my work alongside Nassim Taleb, arguing this case vis-à-vis genetic modification;8 that is, we argue that there is a strong precautionary case against GMOs (even if there is not a strong ‘evidence-based’ case against them), because there is a risk of ruin implicit in genetic engineering, if it goes wrong.

But there is a basic way in which the case of climate is very different from the case of GMOs. For it has been shown beyond reasonable doubt that anything remotely like a business-as-usual path puts us on course for climate Armageddon.9 The basic science of climate change is as compelling as that of tobacco causing cancer,10 and so we cannot pretend that we do not know that it would be insanity to carry on down the road we are driving.

Ever-worsening man-made climate change (ever-worsening, that is, barring a system change, a radical and swift transformation in our attitude to our living planet) is therefore not properly a potential ‘black swan’ event. It’s a white swan: an expected event. It is, quite simply, what anyone with a basic understanding of the situation should now expect. And this means that, tragically, the default expectation, barring us doing something extraordinary, must be for our future to look like (1) or at best (2) from the list I just outlined.

True, there are some significant grey-flecked feathers in the white plumage. We don’t know the exact ‘climate-sensitivity’ of the Earth system,11 and we don’t know all the feedbacks that are likely to kick in, nor just how bad most of them will be. We don’t know how long we’ve got.

Crucially, these uncertainties, properly understood, underscore the case for radical precautious action on preserving our livable climate,12 for uncertainty cuts both ways. It might end up meaning that the fearful problem one was worried about turns out to be somewhat more tractable than we’d feared. Or it might end up meaning that it turns out even worse than expected.

There is an asymmetry here, for as the worst-case scenario for something potentially ruinous gets worse, we need ever more strongly to guard against it. The possibility of a relatively tractable or even beneficial scenario (as with the possibility that anthropogenic climate change may make it feasible for the world’s best champagne to be produced in Britain) is always outweighed by the possibility of a yet more catastrophic scenario (as with the remote but non-zero possibility that...