![]()

1

Picking up the pieces

In 1891 my Irish great-grandfather, James Henry Corballis, published a book called Forty-five Years of Sport. It covered hunting, shooting, fishing, falconry and, as an afterthought, golf. I recommend it to anyone who wants to know how to mount a horse with a loaded gun, or where to place the golf ball in relation to one’s feet before attempting to smite it along the fairway.

Forty-five years ago, in 1966, I took up my first position as a lecturer in psychology. Over the intervening years, I have taught at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and the University of Auckland. I stopped actually teaching a couple of years ago, but I have remained in the sport—primarily as a researcher and writer, with the occasional lecture thrown in. I don’t suppose I have learned or conveyed anything as useful as my great-grandfather did, but, well, it’s been fun, as sport is supposed to be.

In the course of those forty-five years, I have seen rather dramatic changes in the nature of academic psychology. Scientific psychology began in the nineteenth century as the study of the mind. The main technique was introspection, turning the mind inwards to examine what might be there. Not much was discovered, though, probably because the mind does not have access to most of what it actually does—just as a car engine, say, does not itself understand how it works. Introspectionism gave way to behaviourism, a movement started by John B. Watson early in the twentieth century but developed later by B. F. Skinner. And when I came to psychology in the late 1950s behaviourism still ruled. Effectively, the concept of mind was abolished, and replaced with behaviour, the things people—and animals—actually do. Behaviour is directly observable and therefore amenable to measurement and scientific analysis. Behaviourists, though, saw no essential difference between humans and other animals, and psychological laboratories were filled with rats, and later with pigeons, which were considered more acquiescent and less likely to bite. My early experiences as a junior lecturer included making sure that rats were available and suitably placid for students in their laboratory classes. Even so, the odd student was bitten by the odd rat.

Soon, though, there came a rediscovery of the mind, in another revolution that saw the rats disappear, as though inveigled away by some Pied Piper. The pigeons, too, mostly flew away—although some do remain in some departments of psychology with an attachment to the past. Nevertheless, the cognitive revolution brought people back into the laboratory, largely replacing the rats and pigeons. It was heavily influenced by the emergence of digital computing, and by the linguistic theories of Noam Chomsky. The mind was reinvented as a computational device, although it was still studied by largely objective means—such as how quickly people respond to events, and how well they remember things.

Later, psychology discovered the brain, largely through the efforts of Donald O. Hebb, a distinguished Canadian psychologist, one of my mentors and later a senior colleague during my time at McGill. It turned out that through brain imaging and studying the effects of brain injury, we could look inside that large, wrinkled organ squeezed into our skulls to work out what different parts of the brain looked after—memory in the seahorse-shaped piece called the hippocampus, emotion right next door in the amygdala and so on. And, by watching those regions in action while people looked at Jennifer Aniston or listened to Beethoven, we could begin to understand how the mind works. We humans may not have the largest brain in the animal kingdom, but we have proved to be the only animals capable of having a look inside.

The last decade or so has seen further dramatic changes—if not a revolution, then at least a vast broadening of methodology and subject matter. Some interest has again turned to animals, as we try to figure out how something as complex as the human mind could have evolved. Theories of brain function have become more elaborate, so psychology draws on brain science as well as on what people do. The Pied Piper who led the rats away, unlike his predecessor, brought children into the laboratory, so we could learn more about how their mental functions emerge. As the name implies, the cognitive revolution focused on thinking, neglecting emotion, but the new psychology is as concerned with feelings as it is with thought. Most importantly, the mind is now the focus of interdisciplinary study, the blending of information from diverse disciplines, including archaeologists, anthropologists, biologists, geneticists, linguists, neuroscientists, philosophers, as well as psychologists. It’s enough to make the mind boggle.

In these twenty-one short walks, I have tried to convey something of the mosaic of the modern science of the mind. The topics were chosen much as the whim seized me. Many of them are adapted from pieces that were published as a column in New Zealand Geographic, whose word limit restricted them to bite-sized pieces, but enough, I hope, to convey a flavour—and I have embellished some of the original pieces a little. You may find some of them opinionated, but that’s in the spirit of my great-grandfather, and of sport. I thank Margo White for suggesting the original column and James Frankham for agreeing to publish it. I am especially grateful to Sam Elworthy of Auckland University Press for his encouragement, enthusiasm and help over publication of the pieces in book form; and to Louise Belcher, Katrina Duncan and Anna Hodge for helping to make the book more attractive and readable. I also thank my wife, Barbara, for her tolerance while I wrote, but at least she had her golf, possibly inspired by Forty-five Years of Sport.

This book is especially dedicated to the three new ladies in my life: Lena, Natasha and Simone.

![]()

2

Swollen heads

We humans are a swollen-headed lot. We like to think we’re smarter than all other creatures, and perhaps uniquely blessed by some benevolent deity. Nevertheless, we need to be wary of our comfortable sense that we are at the top of the earthly hierarchy, since it provides a too-easy justification of the way we treat other animals. We eat them, kill them for sport, drink their milk, wear their skins, ride on their backs, ridicule them, house them in zoos and breed them to our own specifications.

How then do we justify our self-proclaimed superiority? One way is to appeal to our very swollen-headedness, looking to the brain itself as proof of our status on the planet. This strategy, though, has proven unexpectedly elusive. In terms of sheer brain size, for example, we have to defer to the elephant and the whale, whose brains are more than four times as big as our own. We cannot therefore claim to be the brainiest of creatures. Perhaps, though, the absolute size of the brain is not really a good measure of intelligence. Large animals need large brains simply to control those big bodies, and deal with all of the information that arrives from their large surfaces. So maybe we should consider not the absolute size of the brain, but rather the ratio of brain size to body size.

Here we come out rather better. Our brains weigh about 2.1 per cent of our body weights, while those of our closest cousins, the chimpanzee and bonobo, are about 0.61 per cent and 0.69 per cent, respectively. The figures for the Asian elephant and killer whale are 0.15 per cent and 0.094 per cent, respectively. So far so good—we can dismiss those lofty elephants and voluminous whales as large but fairly dumb. Sadly, though, the mouse comes out better than we do, with 3.2 per cent, and in small birds the ratio may be as high as 8 per cent.

One approach to this problem is to retreat into mathematics, and hope to bamboozle our creature cousins with equations. Other things being equal, smaller animals have larger ratios than bigger animals do. The psychologist Harry Jerison plotted log brain size against log body size across a wide range of species, and then used a technique called linear regression to compute the slope of the line relating one measure to the other. The slope of this line was ⅔, meaning that body size mattered less the larger the animal. This led to calculation of the expected brain size based on body size, and dividing this into the brain weight leads to what Jerison called the encephalization quotient.*

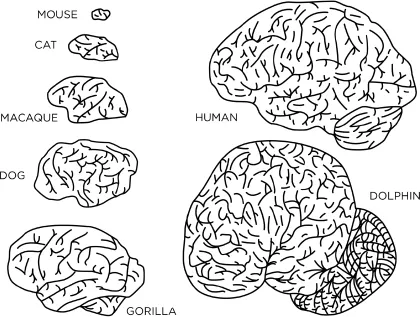

Comparison of brain sizes of various mammals

This quotient turned out to be 7.44 in humans, followed by dolphins at 5.31 and chimpanzees at 2.49. The elephant weighs in, as it were, with a quotient of 1.87 and rats have a miserly quotient of 0.4. The mouse is blessedly reduced to a quotient of about 0.5, so we can stop worrying about that. This quotient also pretty well gets rid of any serious challenge from birds, although comparison is difficult because the slope of the line is rather different for birds. We should be wary of the dolphin, though, which may be closer to us than we’d like to think, and of course there may be other creatures busily working on formulae to prove that they, after all, are top dogs.

Another approach is to examine the neocortex, the outer layer of the brain which houses higher-order functions such as language, thinking and memory. Focusing on the neocortex has the decided advantage of getting rid of birds altogether, since they possess no neocortex at all (other brain areas perform some of the same functions, but let’s not go there). Taking the ratio of neocortex to the rest of the brain places us above other primates with 4.1, closely followed by the chimpanzee at 3.2, gorilla at 2.65, orangutan at 2.99 and gibbon at 2.08.

Group size seems to increase with the ratio. Estimates based on the ratio suggest that gibbons should hang out in groups of about fifteen, orangutans in groups of about fifty, and chimpanzees in groups of about sixty five. These values are pretty close to what has been observed of the animals in the field, except for the solitary orangutan, which seems to prefer its own company. Based on what we know from the brain sizes of our hominin forebears, group size should have been roughly constant at around sixty in the australopithecines, but increased steadily with the emergence of the genus Homo from around 2.5 million years ago, culminating in Homo sapiens. According to the formula, humans should belong in groups of about 148, which is roughly the typical size of Neolithic villages. Of course, modern cities contain vastly more than that, but if you add up the people you are actually acquainted with it may be not too far off the mark. The relation of neocortical size to group size might be taken to mean that neocortical evolution, and perhaps intelligence itself, was driven by the pressures of social interaction.

If the path toward demonstrating our superior brain power has seemed tortuous, we can perhaps at least gain comfort from the thought that we are the only species working on the problem—or so it seems.

![]()

3

On being upright

Humans are unique among the primates (monkeys and apes) in being habitually bipedal. Chimpanzees can stand and even stagger around a bit on two legs, but their regular means of getting around is knuckle walking, in which the forearms serve as forelegs, with the knuckles touching the ground. Since the chimpanzee (along with the bonobo) is our closest relative, it has been commonly assumed that we too once were knuckle-walkers.

The recent discovery of a near-complete fossil called Ardipithecus ramidus, popularly known as ‘Ardi’, challenges this idea. Ardi dates from some five million years ago, close to the point at which our forebears diverged from the line leading to modern chimpanzees and bonobos. She appears not to have been a knuckle-walker, but stood upright. Her foot was nevertheless shaped for grasping, suggesting that she was still primarily a tree-dweller. Her hand was closer to that of a modern human than to that of chimpanzee or bonobo. Some have concluded that bipedalism, at least as a posture for manoeuvring in the forest canopy, may actually date from tens of millions of years ago, and that knuckle-walking in gor...