- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

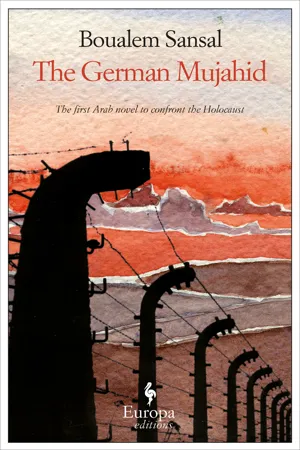

The German Mujahid

About this book

"[A] masterly investigation of evil, resistance and guilt, billed as the first Arab novel to confront the Holocaust" from the Nobel Prize–nominated author (

Publishers Weekly).

Banned in the author's native Algeria, this groundbreaking novel is based on a true story and inspired by the work of Primo Levi.

The Schiller brothers, Rachel and Malrich, couldn't be more dissimilar. They were born in a small village in Algeria to a German father and an Algerian mother and raised by an elderly uncle in one of the toughest ghettos in France. But the similarities end there. Rachel is a model immigrant—hard working, upstanding, law-abiding. Malrich has drifted. Increasingly alienated and angry, a bleak future seems inevitable for him. But when Islamic fundamentalists murder the young men's parents in Algeria the destinies of both brothers are transformed. Rachel discovers the shocking truth about his family and buckles under the weight of the sins of his father, a former SS officer. Now Malrich, the outcast, will have to face that same awful truth alone.

" The German Mujahid deals with the fine line between the destructive power wielded by Islamic fundamentalism today and the power of another movement that left an indelible mark on history: Nazism." — Haaretz (Israel)

"With extraordinary eloquence, Sansal condemns both the [Algerian] military and the Islamic fundamentalists; he decries that Algeria crippled by trafficking, religion, bureaucracy, the culture of illegality, of coups, and of clans, career apologists, the glorification of tyrants, the love of flashy materialism, and the passion for rants." — Lire (France)

" The German Mujahid, winner of the RTL-Lire Prize for fiction, is a marvelous, devilishly well-constructed novel." — L'Express (France)

Banned in the author's native Algeria, this groundbreaking novel is based on a true story and inspired by the work of Primo Levi.

The Schiller brothers, Rachel and Malrich, couldn't be more dissimilar. They were born in a small village in Algeria to a German father and an Algerian mother and raised by an elderly uncle in one of the toughest ghettos in France. But the similarities end there. Rachel is a model immigrant—hard working, upstanding, law-abiding. Malrich has drifted. Increasingly alienated and angry, a bleak future seems inevitable for him. But when Islamic fundamentalists murder the young men's parents in Algeria the destinies of both brothers are transformed. Rachel discovers the shocking truth about his family and buckles under the weight of the sins of his father, a former SS officer. Now Malrich, the outcast, will have to face that same awful truth alone.

" The German Mujahid deals with the fine line between the destructive power wielded by Islamic fundamentalism today and the power of another movement that left an indelible mark on history: Nazism." — Haaretz (Israel)

"With extraordinary eloquence, Sansal condemns both the [Algerian] military and the Islamic fundamentalists; he decries that Algeria crippled by trafficking, religion, bureaucracy, the culture of illegality, of coups, and of clans, career apologists, the glorification of tyrants, the love of flashy materialism, and the passion for rants." — Lire (France)

" The German Mujahid, winner of the RTL-Lire Prize for fiction, is a marvelous, devilishly well-constructed novel." — L'Express (France)

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

MALRICH’S DIARY

NOVEMBER 1996

It was hard for me to read Rachel’s diary. His French isn’t like mine. The dictionary wasn’t much help, every time I looked something up it just referred me to something else. French is a real minefield, every word is a whole history linked to every other. How is anyone supposed to remember it all? I remembered something Monsieur Vincent used to say to me: “Education is like tightening a wheel nut, too much is too much and not enough is not enough.” But I learned a lot, and the more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

The whole thing started with the eight o’clock news on Monday, 25 April 1994. One tragedy leading to another leading to another, the third the worst tragedy of all time. Rachel wrote:

I’ve never felt any particular attachment to Algeria, but every night, at eight o’clock on the dot, I’d sit down in front of the television waiting for news from the bled. There’s a war on there. A faceless, pitiless, endless war. So much has been said about it, so many terrible things, that I came to believe that some day or other, no matter where we were, no matter what we did, this horror was bound to touch us. I feared as much for this distant country, for my parents living there, as I did for us, here, safe from it all.

In his letters, papa only ever talked about the village, his humdrum routine, as if the village were a bubble beyond time itself. Gradually, in my mind, the whole country became reduced to that village. That was how I saw it: an ancient village from some dimly remembered folk tale; the villagers have no names, no faces, they never speak, never go anywhere; I saw them standing, crouching, lying on mats or sitting on stools in front of closed doors, cracked whitewashed walls; they move slowly, with no particular goal; the streets are narrow, the roofs low, the minarets oblique, the fountains dry; the sand extends in vertiginous waves from one end of the horizon to the other; once a year clouds pass in the blue sky like hooded pilgrims mumbling to themselves, they never stop here but march on to sacrifice themselves to the sun or hurl themselves into the sea; sometimes they expiate their sins over the heads of the villagers, and then it’s like the biblical flood; here and there I hear dogs barking at nothing, the caravans are long gone but as everywhere in these forsaken countries, skeletal buses shudder along the rutted roads like demons belching smoke; I see naked children running—like shadows swathed in dust—too fast to know what game they are playing; pursued by some djinn; laughter and tears and screams following behind, fading to a vague hum in this air suffused with light and ash, merging with the echoes. And the more I told myself that all this was just some movie playing in my head, a ragbag of nostalgia, ignorance and clichés seen on the news, the more the scene seemed real. Papa and maman, on the other hand, I could still picture quite clearly, hear their voices, still smell them, and yet I knew that this too was false, that these were inventions of my mind, sacred relics from my childhood memory making them younger with each passing year. I reminded myself that life is hard in the old country, all the more so in a godforsaken village, and then this tranquil veil would tear and I would see an old man, half-paralysed, trying to stay standing to surprise me, and a hunchbacked old woman supporting herself against the flaking wall as she struggled to her feet to greet me, and I would think, this is papa, this is maman, this is what time and hard living have done to them.

Everything I know about Algeria, I know from the media, from books, from talking to friends. Back when I lived with uncle Ali on the estate, my impressions were too real to be true. On the estate, people played at being Algerian beyond what truth could bear. Nothing forced them to, but they conformed to tradition with consummate skill. Emigrants we are and emigrants we will be for all time. The country they spoke of with such emotion, such passion, doesn’t exist, the tradition that is the North Star of their memory still less so. It’s an idol with a stamp of tradition on its brow that reads “Made in Taiwan”; it’s phony, artificial and dangerous. Algeria was other, it had its own life, everyone knew its leaders had pillaged the country and were actively preparing for the end of days. The Algerians who still live there know all too well the difference between the real country and the one we live in. They know the alpha and the omega of the horror they are forced to live through. If it were left to them, the torturers would have been the only victims of their dirty deeds.

On 25 April 1994, the bled was the lead story on the eight o’clock news: “Fresh carnage in Algeria! Last night armed men stormed the little village of Aïn Deb and cut the throats of all of its inhabitants. According to Algerian television, this new massacre is the work of Islamic fundamentalists in the Armed Islamic Group . . . ”

I jumped to my feet and screamed, “Oh God, this can’t be happening!” What I had most feared had happened, the horror had finally found us. I slumped back, shell-shocked, I was sweating, I felt cold, I was shivering. Ophélie rushed in from the kitchen shouting, “What is it? What’s the matter? Talk to me for Christ’s sake!” I pushed her away. I needed to be on my own, to take it in, to compose myself. But the truth was there before my eyes, in my heart, my parents, faces, immeasurably old, immeasurably scared, pleading with me to help them, stretching out their arms towards me as ancient shadows brutally dragged them back, threw them to the ground, shoved a knee into their frail chests and slit their throats. I could see their legs judder and twitch as terrified life fled their aged bodies.

I had thought I understood horror, we see it all over the world, we hear about it every night in the news, we know what motivates it, every day political analysts explain the terrifying logic, but the only person who truly understands horror is the victim. And now I was a victim, the victim, the son of victims, and the pain was real, deep, mysterious, unspeakable. Devastating. Pain came hand in hand with an aching doubt. First thing the next morning, I phoned the Algerian Embassy in Paris to find out if my parents had been among the victims. I was transferred from one office to another, put on hold, and I held, breathless, gasping, until finally a polite voice came on the line.

“What was the name again, monsieur?”

“Schiller . . . S,C,H,I, double L, E, R . . . Aícha and Hans Schiller.”

As I listened to the rustle of paper, I prayed to God to spare us. Then the polite voice came back and in a reassuring voice said: “Put your mind at rest, monsieur, they’re not on the list I have here . . . Although . . . ”

“Although what?”

“I do have an Aícha Majdali and a Hassan Hans, known as Sid Mourad . . . Do those names mean anything to you?”

“That’s my mother . . . and my father . . . ” I said, holding back my tears.

“Please accept my condolences, monsieur.”

“Why aren’t they listed as Aícha and Hans Schiller?”

“That, I’m afraid, I couldn’t say, monsieur, the list was sent to us by the Ministry of the Interior in Algeria.”

Rachel had told me nothing. I never watch TV and my mates don’t even know it exists. We’d never dream about sitting in a dark room watching pictures and listening to people prattling on. If I did hear about the massacre it was only in passing, and I didn’t give a toss. Aïn Deb, Algeria, didn’t mean much to me. We knew there was a war on there, but it was far away, we talked about it the same way we talked about wars in Africa or the Middle East, in Kabul, in Bosnia. All my friends are from places where there’s a war or a famine, when we talk about that shit we never go into detail. Our life is here on the estate, the boredom, the neighbours screaming, the gang wars, the latest Islamist guerrilla action, the police raids, the busts, the dealers, the grief we get from our big brothers, the demonstrations, the funerals. There are family parties sometimes, they’re cool, but they’re really for the women. The men are always downstairs, standing outside the tower blocks counting the breezes. If you go at all, it’s only to say you went. The rest of the time we’re bored shitless, we just hang around on corners waiting for it to be over.

Sometimes, we’ll get a little visit from Com’Dad—that’s what we call Commissioner Lepère. He always pretends like he didn’t know we’d be there: “Hey guys, I didn’t see you there . . . I was just passing . . . ” Then he’ll come over, lean against the wall with us and chat like we’re old friends. Meanwhile we’re standing there wondering if he’s come to phish or philosophize. Both, my brothers, both. Sometimes we’ll feed him a scrap, some bit of bogus information, sometimes we’ll make out like we’re thinking aloud about careers in the service of humanity and the environment. We have a laugh and then say our goodbyes, American style, high fives all round. Com’Dad even buys us all tea at Da Hocine or a coffee at the station bar. Poor bastard thinks it’s a good way of getting in with us. It is so lame. But at the same time we pretend to our mates that we’ve got Com’Dad right where we want him, that we’re always feeding him false information and getting him to pull strings for illegals on the estate. As for Com’Dad, he’ll turn up uninvited at whatever’s going on, he’s there at every party, wedding, circumcision, excision, he pops round to celebrate when people get on a course, get out of prison, get their papers, and he never misses the slaughtering of the sheep at Eid. He always leads the procession at funerals. He’s part of the new school of policing: to know your enemy you have to live with him, live like him.

In Rachel’s garage I found newspaper reports of the Aïn Deb massacre, some from here, some from the bled, Le Monde, Libération, El Watan, Liberté . . . There was a big pile of them. Rachel had highlighted the stuff about us. It ripped my heart out just reading it. There was something sick about it too, the journalists talking about genocide like it was just another story, but their tone was like: “We told you so, there’s something not right about this war.” What fucking war is right? This one’s just wronger than most. And you end up imagining all the horror, the shame piled up on the grief. I had a film of it playing in my head for days, it made me sick to my stomach. This sleepy old village in the middle of nowhere, a moonless sky, dogs starting to bark, mad staring eyes appearing out of the darkness, shadows darting here and there, listening at doors, shattering them with their boots, inhuman screams, orders barked in the night, terrified villagers dragged out into the village square, kids bawling, women screaming, girls scarred with fear clinging to their mothers, trying to hide their breasts, dazed old men praying to Allah, pleading with the killers, ashen-faced men parleying with the darkness. I see a towering bearded man with cartridge belts slung across his chest ranting at the crowd in the name of Allah, then cutting a man’s head off with a slash of his saber. After that, it’s chaos, carnage, crying and screaming, limbs thrashing, savage laughter. Then silence again. A few groans still, soft sounds dying away one after the other, and then a sort of heavy, viscous silence crashing down onto nothingness. The dogs aren’t barking now, they’re whimpering, heads between their paws. Night is closing in on itself, on its secret. Then the film starts up again, only more graphic this time, more screams, more silence, more darkness. The stench of death is choking me, the smell of blood as it mingles with the earth. And I throw up. Suddenly I realise I’m alone in Rachel’s house. It’s pitch black outside, the silence is crushing. Then I hear a dog bark. I imagine shadows slipping through the streets. I calm myself as best I can and I sleep like the dead.

Rachel wrote:

I’ve decided, I’m going to Aïn Deb. It is something I have to do, something I need to do. The risks don’t matter, this is my road to Damascus.

It’s not going to be easy. When I went to the Algerian consulate in Nanterre, they treated me like I was a Soviet dissident. The official stared me in the eye until it hurt, then he flicked through my passport, flicked through it again, read and reread my visa application, then, eyes half-closed, he tilted his head back and stared at a spot on the ceiling until I thought he was in a coma. I don’t know if he heard me call him, whether he realised I was worried, but suddenly, out of the blue, he leaned over to me and, just between the two of us, he muttered between clenched teeth, “Schiller, what is that . . . English . . . Jewish?”

“I think you’ll find the passport is French, monsieur.”

“Why do you want to go to Algeria?”

“My mother and father were Algerian, monsieur, they lived in Aïn Deb until 24 April, when the whole village was wiped off the map by Islamic fundamentalists. I want to visit their graves, I want to mourn, surely you can understand that?”

“Oh, yes, Aïn Deb . . . You should have said . . . But I’m afraid it’s out of the question. The consulate doesn’t issue visas to foreign nationals . . . ”

“Then who do you issue them to?”

“If you get killed out there, people blame us. More to the point, the French government prohibits you from travelling to Algeria. Maybe you didn’t know that, or maybe you’re just playing dumb?”

“So what do I do?”

“If your parents were Algerian, you can apply for an Algerian passport.”

“How do I go about that?”

“Ask at the passport office.”

After three months of running around, I finally got my hands on the precious documents I needed to apply. Getting Algerian papers is without doubt the most complicated mission in the world. Stealing the Eiffel Tower or kidnapping the queen of England is child’s play by comparison. Phone all you like, no one ever answers, paperwork gets lost somewhere over the Mediterranean or is intercepted by Big Brother to be filed away in a missile silo in the Sahara until the world crumbles. It took me five registered letters and two months of fretful waiting just to get a copy of papa’s certificate of nationality. When I finally got the papers, I felt like a hero, like I’d conquered Annapurna. I rushed back to the consulate. The passport officer proved to be every bit as intractable as his colleague at the visa desk, but, in the end, officiousness had to defer to the law. God it must be degrading and dangerous to be Algerian full time.

At the Air France office they looked at me as though I had shown up with a noose around my neck ready to hang myself in front of them. “Air France no longer flies to Algeria, monsieur,” the woman snapped, shooing me away from her desk. I went to Air Algérie, where the woman behind the desk could think of no reason to send me packing, but she tossed my brand new passport back at me and said, “The computers are down. You’ll have to come back another day. Or you could try somewhere else.”

Only when I finally got the whole trip sorted out did I tell Ophélie and, as I expected, she threw a fit.

“Are you crazy? What the hell do you want to go to Algeria for?”

“It’s business, the company is sending me to assess the market.”

“But there’s a war on!”

“Exactly . . . ”

“And you said you’d go?”

“It’s my job . . . ”

“Why are you only telling me this now?”

“It wasn’t definite until now, we needed to find someone well connected in the regime.”

“Go on then, get yourself killed, see if I care.”

If sulking was an Olympic sport, Ophélie would be a gold medalist. At dawn the next morning, while the dustmen were making their rounds, I crept out of the house like a burglar.

The journey itself proved to be much easier than the consulate, the airlines and Ophélie predicted. Getting to Algiers was as easy as sending a letter to Switzerland. Unsurprisingly, Algiers Airport was just as I left it in 1985 when I came to bring Malrich back home. It was exactly how I remembered it, the only difference was the atmosphere. In 1985, it was low-level distrust, now it is abject terror. People here are scared of their own shadows. There’s been a lot going on. The airport was bombed not long ago, there’s still a gaping hole in the arrivals hall, you can still see spatters of dried blood on the walls.

I found myself out on the street, in the milling crowds, under a pitiless sun. What was I supposed to do now, where was I supposed to go? From my clothes, it was obvious I was a foreigner, so I didn’t go unnoticed. I hardly had time to wonde...

Table of contents

- MALRICH’S DIARY OCTOBER 1996

- MALRICH’S DIARY NOVEMBER 1996

- RACHEL’S DIARY TUESDAY, 22 SEPTEMBER 1994

- Shemà

- MALRICH’S DIARY WEDNESDAY, 9 OCTOBER 1996

- RACHEL’S DIARY MARCH 1995

- RACHEL’S DIARY APRIL 1995

- MALRICH’S DIARY 31 OCTOBER 1996

- MALRICH’S DIARY SATURDAY 2 NOVEMBER 1996

- MALRICH’S DIARY DECEMBER 1996

- RACHEL’S DIARY JUNE–JULY 1995

- RACHEL’S DIARY 16 AUGUST 1995

- MALRICH’S DIARY 15 DECEMBER 1996

- MALRICH’S DIARY 16 DECEMBER 1996

- RACHEL’S DIARY ISTANBUL, 9 MARCH 1996

- RACHEL’S TRIP TO CAIRO 10-13 APRIL 1996

- MALRICH’S DIARY JANUARY 1997

- MALRICH’S DIARY FEBRUARY 1997

- RACHEL’S DIARY FEBRUARY 1996 AUSCHWITZ, THE END OF THE JOURNEY

- MALRICH’S DIARY FEBRUARY 1997

- RACHEL’S DIARY 24 APRIL 1996

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The German Mujahid by Boualem Sansal, Frank Wynne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.