![]()

Greenland

THE WILD WEST

ICE WAS SPRINKLED on the ocean like chalk crumbled over a mirror. From thirty thousand feet the monstrous icebergs were inconsequential, snapped off and drifting free from the glaciers which eased themselves through the corridors of mountains lining the coast.

The eastern coast of Greenland mocks attempts at description; it is sublime. The largest ice-cap in the world outside Antarctica flows out into the Atlantic under the pressure of its own unimaginable weight. The mountains that struggle out of the ice are dwarfed by it like pebbles in a mill-race, but from below they would have been seen to soar to over three thousand metres. Most of them are unclimbed and many are unnamed. The name given to these islands of rock in a sea of ice is nunatak, an Inuit word, reminding the West that Inuit peoples mastered these landscapes long before Europeans ever did.

The late evening sun was lowering, casting shadows from the peaks that stretched for kilometres across the ice in jagged silhouettes. The glaciers coiled and flowed between them in whorls. The same icebergs which had awed and inspired Brendan one and a half millennia before lolled together in clusters on the edge of the ocean.

The aeroplane left the coast behind and rose over the dome of the ice-cap. The ice progressively submerged even the highest mountains, leaving only an immense expanse of unblemished snow. Something in witnessing such rare beauty seems to excite and inspire, knocking down the barriers between individuals and revealing a need to share experience. All down the aeroplane people grinned and laughed, swapped seats and binoculars with one another and called upon total strangers to come to their window and look out over the ice. Though we had flown three hours in silence, by the time we landed on the western coast the passengers were chattering together about the beauty of the country, the stories they had heard of it, and where they hoped to travel in Greenland, one of the last frontier lands on earth.

If Shetland was discovered through a quest for knowledge, the Faroe Islands on a pilgrimage for God, and Iceland in a drive for expansion, then Greenland was discovered in a last-gasp bid for survival. Eirik the Red was a murderer. He had slaughtered so many people in Iceland that if he did not find another land to live in, he would be killed himself. He did not really have any choice but to find a new world.

There had been clues about lands to the west. Since Brendan there had persisted among the Irish the tradition of a great island to the west across the ocean. Called Tir-na-n-Ingen, or ‘the Land of Virgins’, the legend was reinforced by the stories of St Brendan’s Land of the Promise of the Saints. An Icelander called Are Mársson said he drifted to ‘Great Ireland’, where he had been baptised by chiefs in white garments. Though probably total fantasy, this island was said to be six days’ sail west of Iceland and to be populated by Irishmen who had been living there for centuries. More credibly, a Norseman on his way to Iceland had been blown off course and seen some barren rocks sticking up through the fields of ice to the west. Eirik was not put off by the bleak picture that was painted of the islands, being no stranger to scraping his living in harsh circumstances. He had come to Iceland from Norway only a few years before as a fugitive, and had eked out a life on the poor and ice-ridden land that was all that was left unclaimed at the end of the tenth century. The murders he had committed there had been partly in self-defence, and so he was sentenced only to ‘minor outlawry’. If he managed to stay alive for three years outside Iceland he would be safe to return.

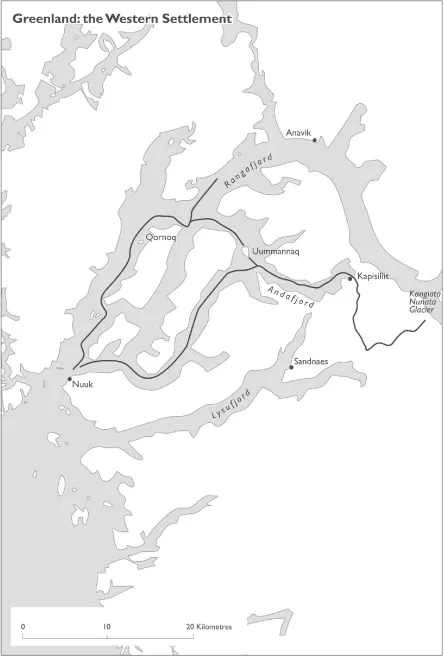

He found the ice-clogged seas and the stony islands to the west of Iceland but continued on, rounding a cape in the south and then up the western coast of a new land where he found towering mountains backed by ice-caps, and a coastline slashed with deep and lush fjords. It was colder than Iceland, but further south and so enjoyed shorter winters and a less capricious climate. Out at the mouths of the fjords, banks of fog and mist rolled down over the ice-fields, but deep inside the valleys the summers were warm and the skies were clear. There were caribou and seals to hunt and green pasture for sheep and cattle. For a man used to the barrens of Iceland it was a rich country.

After three years exploring the coastline he had found two areas that seemed verdant enough to support the Norsemen’s grazing economy. He called the whole place ‘Greenland’ and sailed for Iceland to rejoin his family and persuade others to join him in his New World.

In his absence Iceland had fallen on hard times. The soil was continuing to leach away, there had been another famine, and people gathered to hear about any opportunity to start anew. Contemporary accounts describe those lean years at the end of the tenth century: ‘There was a winter of great calamity in the heathendom in Iceland… Men ate ravens and foxes, and much ill fit to eat was eaten, while some had old folk and infants slain and cast over the cliffs. Then many men starved to death, while some took to stealing.’

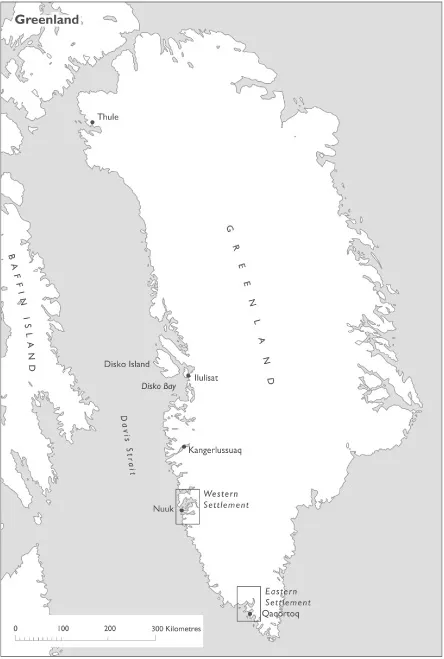

Twenty-five knörrs, carrying between six hundred and a thousand emigrants, were loaded up and sailed for Greenland in the spring of 986. Times in Iceland must have been desperate. Only fourteen made it, the others being driven back or wrecked. Eleven ship-loads settled around the southern tip of the new land where Eirik had first come ashore, and the area was named the Østerbygd or ‘the Eastern Settlement’. Three more adventurous chieftains continued on with their ships to the second area Eirik had found which lay further to the north. Its landscape was wilder, bleaker, more exposed and when settled it became the remotest outpost of European civilisation. Lying seven hundred kilometres further to the north and the west of the Østerbygd, it was called Vesterbygd or ‘the Western Settlement’.

Santa Claus was bleached by the twenty-four hour sunlight. He announced the passengers’ arrival in Greenland in Danish and English. The poster he was printed on was torn and ageing, the legacy of a tourism venture that was past its best. He looked out of place and out of season among the bare screes and scrublands of the fjord. Depending on your point of view the snows were either a few kilometres in towards the ice-cap or a few months away. Herds of caribou grazed on the far hillside in the midnight sunlight, and clouds of biting flies billowed like smoke around the heads of the runway workers. The air was very clear. Kangerlussuaq, or Søndre Strømfjord in colonial terms, is the gathering point of Greenland; all flights in and out of the country go through it. It lies about halfway down the western coast, tucked in close to the ice-cap, and was originally built as a military base. The Americans helped defend the North Atlantic from there while Denmark was occupied by Germany. They liked Greenland, and afterwards tried to buy it. Denmark refused, but in gratitude the Americans were allowed a concession: Thule Airbase, up at 77° north and only a few hundred kilometres from the North Pole.

At the turn of the twenty-first century Thule was still permanently staffed, and armed, by the Americans. Their determination to stay there is understandable; as occupiers they are only following an ancient Imperial tradition. Since the time of Pytheas the word Thule has been a symbol of the ultimate north, and the control of it has long been held to be the highest honour by those seeking domination in world affairs. In his Georgics Virgil wrote in praise of Caesar Augustus, ‘whether you come as a god of the wide sea, and sailors pay reverence to your divine presence alone, farthest Thule obeys you.’ Charles V of Spain too, when he sent his fleets to build an Empire in the New World had banners made declaring ‘tibi serviat Ultima Thule’, or ‘Let Farthest Thule Obey You’.

Pytheas’ lost book has evidently inspired the empire-builders of the world right up to the modern day. The Americans look like they are there to stay. There are other permanent settlements in the world farther north than Thule Airbase in Greenland, but none of the others have nuclear weapons. The Greenlanders want them out. The Danes allow them to stay. It is another tension in their currently unhappy relationship.

There had been a strike at Kangerlussuaq among the baggage handlers. Greenland’s population is so small and its communications so dependent on this one airport that a handful of men had held the country to ransom. Danish scout groups and tired businessmen slept on their suitcases in the small cafeteria. A smiling Greenlander reassured a bunch of yelling women that flights would soon be resumed. Outside on the terrace a few bored individuals sat leaking cigarette smoke and idly swatting mosquitoes. Children played on the swings, excited by the light and the lateness and the novelty of the place. I bought a plastic cup of coffee, sat down on my rucksack and waited.

‘Oldest rocks in the world,’ he said.

I was eavesdropping. The speaker was a tall and well-built man in his thirties with a black tangle of hair and a jaw bristling with benign self-assurance. His chequered shirt made him look like a Canadian lumberjack.

‘Sorry, could I ask what was that you said?’ I asked.

He turned round. ‘Round here are the oldest rocks in the world – well, further south, down around Nuuk. That’s where we’re heading, my wife and I. And you?’

‘I’m going to Nuuk too,’ I said.

‘We’re going off to camp for a couple of months up near the ice-cap, get some samples.’ They were geologists, he said, from St John’s in Newfoundland. They had a commission to collect samples from two different sites in the fjord system inland from Nuuk. Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, has a population of 14,000 and is the largest settlement in the country. The Danes, he told me, were trying to find mineral wealth in Greenland, some economic return for the hundreds of millions of kroner they pay annually to prop up the Greenlanders’ economy. ‘That’s where we come in,’ he grinned, revealing ivory rows of perfect teeth.

As recently as 1933 Norway was still laying claim to being Greenland’s colonial master. Iceland, the Faroes and Greenland had all originally been Norwegian colonies, and even Eirik the Red’s descendents had shown loyalty to the Norwegian throne when it suited them. But by 1387 the Norwegian, Swedish and Danish crowns had all merged in the familiar mediaeval drama of political marriages and untimely deaths. By 1450 a treaty had been ratified swearing the three countries’, ‘lasting, eternal and inviolable union.’ Before recent independence Norway had spent the five hundred years since as an appendage of either Denmark or Sweden. When it wrested itself from Swedish control for the second time at the turn of the twentieth century, it found that it had lost all of its dependencies in the process. An attempt was made to occupy the eastern coast of Greenland, but in 1933 the International Court in the Hague deemed it unlawful. Denmark were the owners, Norway the squatters.

‘I guess Denmark’s hoping that if the Greenlanders find enough wealth to support themselves, they’ll show some gratitude to the Danes for supporting them all this time,’ he said. ‘But it is a gamble. Some Greenlanders are pretty pissed off with the Danes.’

He told me that the delays were a common occurrence here and that in Greenland the local airline, Grønlandsfly, is nicknamed by the locals ‘Imigafly’, best translated as ‘Maybe Airways.’ As soon as he said it there was an announcement: the flight to Nuuk would leave shortly. We gathered up our bags and ran out across the tarmac to the small aircraft. People who had been waiting to fly north for two days groaned and turned back to sleep. When the plane took off the sun, having never set, was already beginning to climb into the north-eastern sky.

Eirik the Red and his followers were emigrants. They were men and women who were unafraid, who had a vision of a better future, who were willing to work hard and who knew no other life than one of risk. Within a decade the new settlements were thriving. It was a rich country. The Norsemen had never seen such a profusion of seals, whales and game, and further north there were walrus, narwhal, beluga, and the greatest quarry of all: the polar bear. They grew wealthy on trade in these rare commodities. Walrus tusk was a precious alternative to elephant ivory, European access to which was blocked at that time by the Islamic Caliphate. Narwhal tusk passed off as unicorn horn was a cure for all forms of pestilence, and polar bear furs were in demand for the hearths of the European super-rich.

To begin with, it was a good land to settle in, but the momentum of the migrants carried them on further across the ocean.

There are two sagas which describe the discovery of North America by the Greenlanders. One is called Grœnlendinga saga, ‘The Saga of the Greenlanders’, and the other is Eiríks saga rauđa, ‘The Saga of Eirik the Red’. Eirik’s saga is more detailed but apparently less reliable, and seems to have been a later work more concerned with Christianising the legends of the Greenlanders. But it is surprising how much they agree.

It seems that Leif Eiriksson and then his family members did travel to a new land which lay to the south west of Greenland. He found grapes growing ...