![]()

CHAPTER ONE

PRIVATIZING WAR

Al J. Venter originally wrote this report, headed “Privatizing War”, for Britain’s Jane’s Information Group. At the time he was Africa and Middle East correspondent for Jane’s International Defense Review and special correspondent for Jane’s Intelligence Review, Jane’s Terrorism and Security Monitor as well as Jane’s Islamic Affairs Analyst. For a long time the article appeared on the website of Sandline International, founded by former British Army officer Lieutenant Colonel Tim Spicer.

For more than three weeks in early 1999, a lone Mi-17 gunship – flown by a South African helicopter pilot, Neall Ellis – was all that stood between a depleted Nigerian ECOMOG force and the collapse of the Sierra Leone Government. Anarchy was a whisker way.

Alone at the controls for 12 hours a day without a break – except to refuel and gun up again – he struck at rebel units in and around the capital. During the course of it, Ellis took heavy retaliatory fire and, as he later told Jane’s Intelligence Review 1, “while the rebels had a lot of RPGs and SAMs, I suppose I had my share of luck.”

The Washington Post’s former West African correspondent James Rupert tells of an interesting insight to that period in a report from Freetown, Sierra Leone 2.

When Sierra Leone’s lone Mi-24 combat helicopter blew an engine late last year, he wrote, it meant disaster for the government. The ageing Soviet-built gunship had been the government’s most effective weapon against a rebel army that was marching on the capital.

Officials scrambled to repair the machine. But rather than rely on conventional arms dealers, they took bids from mining companies, gem brokers and mercenaries, most of whom held – or wanted – access to Sierra Leone’s diamond fields. The government finally decided to buy $3.8 million-worth of engine, parts and ammunition through a firm set up by Zeev Morgenstern, a senior executive with the Belgium-based Rex Diamond Mining Corporation.

In the end, the parts proved unsuitable and the helicopter stayed on the ground. The rebels seized Freetown, killing thousands of residents and maiming many more, Rupert said. Since then the Freetown government hired a bunch of Ethiopian technicians to work on the “antiquated” Hind and that was what Ellis flew.

The Royal Air Force sent four of its Chinook helicopters to help in the war against the rebels in Sierra Leone. Neall Ellis had been fighting a rear guard action for almost a year by then but he had gained much experience in the enemy’s abilities and tactics. All this was put to use by the British after they arrived. (Photo: Author’s collection)

This privatization of conflict has included the use of fuel-air bombs in an African war. The Angolan Air Force dropped them on UNITA positions around the strongholds of Bailundo and Andulo in the country’s Central Highlands shortly before Savimbi was forced back into the bush, in late 1999.

Luanda’s newly acquired Sukhoi Su-27s were unleashed in the attacks and the bombs used were a legacy of an earlier period when mercenaries fought for the government. Interestingly, deployment of fuel-air bombs in an African insurgency or civil war is a concept that has been around a while. Referred to as “the poor man’s atom bomb”, its use was first mooted when the South African Army was engaged in a succession of border wars in the early 1980s.

Swapo’s elaborate tunnel and trench-line systems in south Angola – a legacy of Vietcong involvement with the Marxist Luanda government – had become a feature of insurgent countermeasures, if only to avoid taking casualties from South African aircraft. These bombs were considered a means of driving the guerrillas into the open.

The South African mercenary group Executive Outcomes (EO) first used fuel-air bombs in Angola in 1994 against UNITA infantry and mechanized concentrations north of Luanda and that option was again explored after this South African group went into Sierra Leone. This writer was present when plans to bomb Foday Sankoh’s rebel headquarters near the Liberian border – using fuel-air bombs – were discussed. By then a lot of research had gone into the issue, including the fact that it would have been an ideal weapon to use in the close hillside confines where the rebels had bolstered their defenses. EO pulled out of Freetown before these plans could be implemented.

Judging from the extent of the destruction of some areas around Savimbi’s headquarters near Bailundu, reports indicated that fuel-air bombs might have been used in Angola’s war. Civilian eyewitness accounts detailed the size and shapes of canisters dropped, as well as the behavior of the explosives. Some said that from a distance it resembled napalm, something that they had seen often enough in the past.

Fuel-air bombs, while not illegal under the Geneva Convention, are regarded by international bodies as transgressing human rights. A former EO source told the Johannesburg Mail & Guardian that a cache of South African-made fuel-air bombs had been left behind in Angola in 1994 after Savimbi signed the Lusaka peace accord.

It is a gradual process, but a consequence of the spate of brush-fire conflicts throughout much of the Third World is that war is being privatized. There is good reason: Western governments are reluctant to put their boys at risk for obscure causes that might be otherwise be difficult to explain to their electorates.

Two important events underscore this development. The first, early in November 1999, was a repeat of the original Executive Outcomes operation. MPRI, a large private American military planning group with close ties to the Clinton administration, was dispatched to Angola to train the Angolan Army of President Eduardo dos Santos. According to the Mail & Guardian, Military Professional Resources Inc. (MPRI) reached an accord with Luanda to take the Angolan Army (FAA) in hand, very much as EO had done in the past.

Shortly afterwards, another private South African force became part of the UN contingent sent to Dili in East Timor, not long after that tiny former Portuguese colony had achieved independence. Consisting mainly of people of mixed blood (“Colored”, in South African racial parlance) it was intended that its men blend in with East Timor locals. The force was assembled and trained by two Durban-based security companies (Empower Loss Control Services and KZN Security). Their job – under the aegis of the UN – was to work in an undercover capacity in the territory.

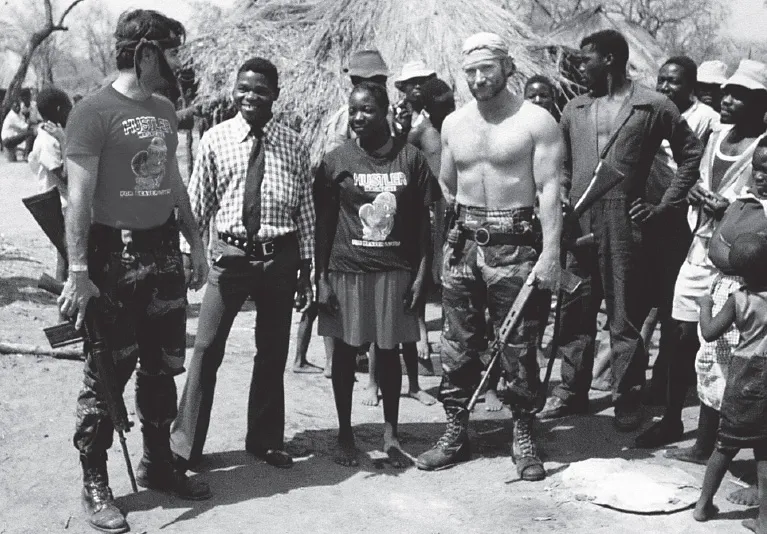

American mercenaries are always a feature of foreign wars, whether serving in the French Foreign Legion or as “freelancers” in the Rhodesian conflict. Dana Drenkowski flew 200 combat missions with the USAF in Vietnam (left) and then went to Rhodesia, this time accompanied by another veteran, shirtless Jim Bolen. (Photo: Dana Drenkowski)

Jose “Xanana” Gusmao, leader of the National Council of the East Timorese Resistance, told South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki at the time that he did not trust any of the bodyguards that the Indonesians might have provided, which is why he asked for the South Africans who would also double in that role.

With Executive Outcomes having subdued several rebel uprisings in Angola and Sierra Leone in the mid-1990s, African states have been the first to observe a proliferation of private armies.

So, too in South America and certain parts of Asia. South African helicopter gunship pilots flew as mercenaries in Sri Lanka, not long before a “force-for-hire” employed by the British company Sandline International was to have been deployed in Papua New Guinea. Australian regional politics (and PNG handouts) got in the way of that little exercise.

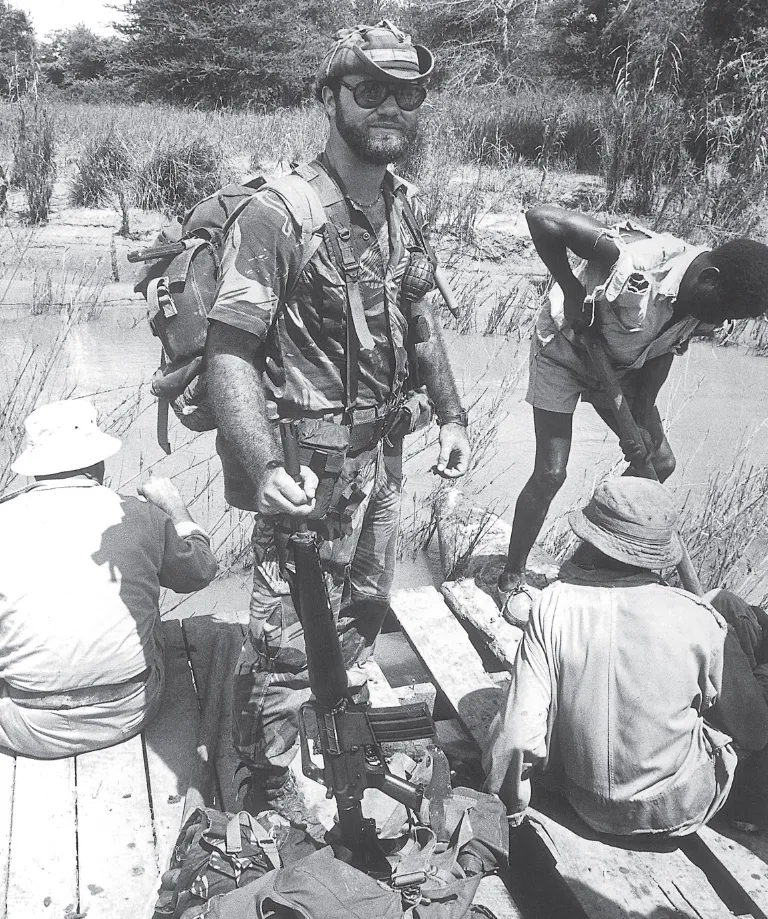

American mercenary Dave McGrady seen here during a bounty hunting operation with the author in Rhodesia’s north-west. He saw a lot of action in Africa and later, with the mainly Christian, Israeli-recruited South Lebanese Army in the Middle East. (Photo: Author)

The track record is interesting. The first time a South African mercenary force went into Sierra Leone in 1996, it took them less than three weeks to “sanitize” a region around the capital half the size of Connecticut. A week later, a small, mainly-black force comprising 85 men – led by two surplus Russian-built BMP-2 IFVs and with a couple of Mi-17s for top cover – drove Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels out of the Kono diamond fields, 120 miles into the interior.

That operation took three days and crippled the rebels: diamonds were to have funded their revolt.

At no stage did the South Africans ever have more than a couple of hundred men in Sierra Leone (it was usually only 80 or 100), supplied twice monthly from Johannesburg by Executive Outcomes’ own Boeing 727.

The war in Sierra Leone only tells part of the story, because by the 1990s there were mercenary involvements in a spate of civil wars, revolts, coups and uprisings in Africa, the Middle East, South and Central America and elsewhere. By early 1999, news agencies reported former Soviet Union pilots supporting the Angolan rebel group UNITA, though their role was more transport than combat-related.

By May 2000 there were also Russian and Ukrainian pilots flying MiG fighters on both sides of the Ethiopian-Eritrean war. Indeed, US News and World Report carried details and a photo of Colonel Vyacheslav Myzin emerging from the cockpit of one of Ethiopia’s newly acquired Su-27s after a demonstration flight 3. He was labeled one of Africa’s “new mercenaries.” Similarly, in the Congo (both before and after Kabila ousted Mobutu), Serbs, South Africans, Croats, Zimbabweans, Germans, French and other nationalities were involved, fighting both for and against the government.

Then came Angola, with former Executive Outcomes personnel – almost all exclusively Southern Africans – involved on both sides of a civil war that had been going on intermittently since 1975 (not counting the 13-year anti-colonial guerrilla war against the Portuguese, prior to that). Significantly, some of these soldiers trained and fought alongside Angolan government forces in the mid-1990s 4.

South African mercenaries attached to Executive Outcomes took the lead against the rebels in Sierra Leone early on in this horrific struggle. Their numbers rarely exceeded 150 and they took less than a year to force the opposition to the negotiating table. There were 16,000 United Nations troops in the country at the same time and they achieved absolutely nothing. British forces under then Brigadier David Richards eventually took over and within months had crushed the rebels. (Photo: Roelf van Heerden)

With EO’s demise in January 1999, following South African Government pressure to disband and an Act of Parliament in Cape Town making any kind of mercenary activity illegal, a number of old hands surreptitiously switched sides and for some time directed Savimbi’s efforts against the government. In the end, Luanda’s dominance in the air prevailed and UNITA was forced to the conference table, finally ending that civil war. Dr Jonas Savimbi was lured to attend a meeting with “friends” and murdered.

Other mercenaries (again, of African extraction) are said to have been seen in action with rebel contingents in Guiné-Bissau. In Senegal’s Cassamance Province, early reports speak of foreign veterans (possibly French) helping dissident rebels.

In the Sudan, Iraqi pilots flew some of its planes in operations against southern largely Christian Nilotic dissidents, almost exclusively black, with other reports speaking of chemical weapons being used against them. The Khartoum government also salted its ground forces with Afghan mujahedeen, Yemenis and other foreign nationals against a Christian/animist uprising in the south.

Mercenaries were also active in uprisings in Burundi, the Congo (Brazzaville), Rwanda, Uganda and in what was once termed the Northern Frontier District of Kenya where most of the insurgents are Somali, some backed by warlords, others acting on a freelance basis. As we have learned from numerous news reports, that struggle, now involving an al-Qaeda offshoot that calls itself al-Shabab, goes on.

There have been more reports of mercenary activity in the Comores Archipelago where French national Bob Denard originally overthrew an established government, following a seaborne invasion in 1978. After arresting President Ali Soilih (he was later shot), Denard – backed by his mostly French and Belgian clique that had the blessing of French Intelligence – ended up ruling the country as his private fief. Denard was finally ousted by a French naval task force, 11 years later 5.

Elsewhere, there were Russian, French, Chechnyan and other mercenaries active during the war in Kosovo (and earlier, in ...