![]()

CHAPTER 1

DEATH OF THE FIGHTING MAN – IN TIMBER AND STONE

1066–1400

KING HAROLD NEVER SHOULD HAVE LOOKED UP. The arrow in the eye may well be a myth but there is no doubt he lost the battle, his throne and his life. Not a good day however you look at it. It was once accepted that Britain had no real castles prior to those nasty, greedy Normans storming across the Channel. We assume they brought the idea with them, using their timber fortresses (brought with them, flat pack style), to give them a head start on oppressing the country. The reality is a bit more mixed – there was a form of fortress building before 1066. The materials were mostly timber with some stone but there was no motte and bailey. A ringwork was an early form of enclosure castle; it sat on top of a circular mound, a bit like a flatter kind of motte. Inside a wooden palisade were a range of buildings, possibly with a defended gateway. It was a kind of fortified manor house, maybe lacking the strict military application of the motte.

Fifteen years before the battle of Hastings, a monkish chronicler from Peterborough waxed lyrical. Today, we would describe the style as ‘tabloid’. He recounts the building of what sounds very much like a castle by a gang of King Edward the Confessor’s Norman cronies, describing it as an outrage. In fact these yobbish Norman interlopers were an outrage in general but, as Marc Morris describes in his excellent study, this clearly suggests building activity prior to Hastings.

Reconstructed wooden keep at Saint-Sylvain-d’Anjou, France. (Julien Chatelain, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

What is a motte? From the days of Charlemagne onwards, local lords in France and Normandy were building fortified dwellings/ garrison outposts. First would come the digging of a larger outer platform (the bailey) with a much steeper conical mound behind (the motte). Both were surrounded by defensible timber cordons and linked by a flying bridge or stairway. Domestic buildings and offices clustered in the bailey while a strong wooden tower was erected on the motte. The latter was not generally residential. It was a last-ditch redoubt which could be held by the few against the many if the many had already broken into and taken the bailey.

At the same time the castle, as the centre of an estate, was a base from which a lord could hold down his lands with a well-trained mini-squadron of mounted, mailed and well-armed knights. Its very strength proclaimed his status – a highly visible badge of his control. He, his family and retainers lived there, his manorial court was held there, it was where he collected his rents. In terms of pure defence, the motte would be situated to control settlements, guard river crossings and coastal estuaries. They were at once tactical; a means of both offence and defence, and strategic, in that they held down large tracts of land. Simple, relatively cheap yet highly effective, they offered a means of stamping a conqueror’s seal over subject territory. And for anyone who proves recalcitrant there was always the option of a spot of harrying.

How were motte and bailey castles actually built? Construction demanded a good and ready supply of timber, ideally oak, in which England abounded at the time of the conquest. Logs were felled and dragged by horse transport onto site where they were split, using wedges, into planking. A decent-sized oak yielded as much as a thousand square feet of cladding. The boards could be dressed down with axes to a smooth finish, something that did not require highly specialised craftsmen – village carpenters were adequate. Internal buildings were timber framed with wattle-and-daub panels, again, an undemanding and familiar technology. Roofing would require slates or timber shingles. Thatch, so easy to fire, was avoided.

While timber is very useful, it has a telling number of disadvantages. It’s cheap, plentiful, light to work by comparison with stone and quick to build. But it deteriorates very quickly – the life span may be as little as 30 years. Worst of all, it’s vulnerable to fire. Stone may be fire resistant but it is also more expensive, demands highly skilled craftsmen, takes longer and weighs more. When some early timber castles were rebuilt in stone, the ground-works intended to support timber couldn’t bear the additional load. Prudhoe in Northumberland is a prime example; the walls slid outwards because the base could not be sufficiently consolidated.

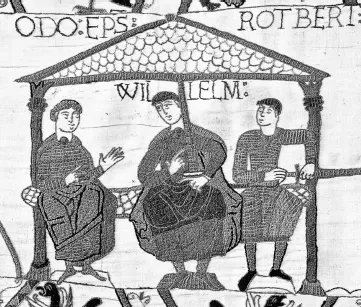

Standards of finish and decoration varied considerably. Some examples depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry indicate high levels of artistic embellishment but this was by no means universal. Motte building was ‘statist’ only insofar as the king was a guiding force. Each castle was built by an individual lord or knight who was free to exercise his own taste within his means – spartan garrison outpost or luxury gentleman’s residence. Baileys were probably more crowded than we might assume from illustrations, which tend to show just a few buildings. A castle might actually have looked more like a fortified village, rammed with jostling interior structures. Even the motte itself, origin of the shell-keep, possibly had a number of buildings crowded behind its palisade.

Castles were located with a purpose. That inevitably meant strategic priorities took precedence over existing civilian settlements. We know that at Cambridge 27 homes were flattened to clear the ground and substantially more at Lincoln. Marc Morris has looked at William of Poitiers’ claim that the Conqueror, having subdued Dover, re-fortified the place, throwing up new defences in just eight days. Ingeniously, Morris looks at Victorian pioneer statistics which show a sapper was expected to shift 15 cubic feet of earth per hour (0.75m3), or 80 cubic feet (4.0 m3) in a day. As a typical motte required 10,000 cubic metres of earth (22,000 tonnes) to be shifted and packed, it would need five hundred navvies to get the job done in just over a week. One can imagine Duke William was in a good position to summon such a workforce.

All the choicest fiefs in the south went to those closest to William and those who had stood beneath his banners by Senlac Hill. Those less well connected or who turned up after the show didn’t do as well and few were that keen on heading north. The king appointed Robert Fitz Richard as castellan at York (building a motte where Clifford’s tower now stands). Robert de Comines pushed further north to Durham. These Normans were pretty rough even by local standards and began with a looting spree. The locals took exception and struck back in an untidy running fight. De Comines and his survivors barricaded the Episcopal House but were subsequently burnt alive.

Image from the Bayeux Tapestry showing William with his half-brothers. William is in the centre, Odo is on the left with empty hands, and Robert is on the right with a sword in his hand. (Wikimedia Commons)

York was next. Fitz Richard was cut down in ambush and what was left of the garrison besieged in their new motte. Relief proved tricky, the Normans oddly timorous. It took William’s personal intervention to stem the rot and re-establish royal authority. He reinforced the defences, increased the number of knights and appointed William Fitz Osbern to lead. This replacement had learnt nothing however and continued a reign of terror. In autumn 1069, King Swein of Denmark supported the rebels with a fleet and force of assorted mercenaries. This tipped the odds again and the Normans in York were defeated in a fiery finale.

A medieval form of planning consent, a licence to crenellate, was needed to fortify, or ‘crenellate’ i.e. add battlements, to a structure and make it a fort. This system persisted from the 12th century or possibly earlier to the 16th century. The Civil Wars of Stephen and Matilda had witnessed a whole slew of illegal castles chucked up by feuding barons. Most applicants were drawn from the gentry rather than magnatial class and quite a few licences were issued to women. For a dispute over licensing, see Chapter 4.

By now King William had had quite enough of his troublesome northern subjects. He paid the Danegeld and bought the Scandinavians off. This might have been dangerous but they never came back and he sorted out the locals with a policy of fire and sword. The Harrying of the North was an exercise in terror of biblical proportions, ‘He created a desert and called it peace.’

The Bigod Earls of Norfolk joined the dissenting magnates in Stephen’s unhappy reign. Henry II confiscated four of the then earl’s fortresses and decided to build a new one: a demonstration of centralised power.

Orford, which was constructed between the years 1165 and 1173, is both remarkable and unique. It rises like some mythical enchanted tower, alone on its isolated shore and 12 miles (20 km) northeast of Ipswich. It has a circular tower rising 90 feet (27m) from the flat scrubby plain. The symmetry is compromised by three angular clasping towers projected out from the width of the core (49 feet or 15m). Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful job with light airy chambers cleverly angled to maximise the morning’s glow.

Orford is around two miles (3.2 km) from the sea – the site runs down towards the River Ore. Most of the outworks have gone but it had a curtain wall, studded with four towers, pierced by a single fortified entrance block. There’s some debate as to why Henry opted for this particular, idiosyncratic shape. Current thinking is that this was as much a political as a military statement. In fact the design partly compromises the defence and shows byzantine influences. The angular profile and masonry banding are reminiscent of the great Theodosian walls of Constantinople.

We tend to view keeps as just part of a wider defence complex involving the great tower but also a defensible courtyard with a curtain wall, possibly with additional small towers and a fortified gateway. In France the tower is called a donjon (from the Latin ‘dominus’ or lord). For our purposes the terms ‘great tower’, ‘keep’ and ‘donjon’ are interchangeable. In some instances, such as at Richmond, the tower has formed a later addition to an existing enclosure castle (here, the great tower replaced an earlier gatehouse). Most are square or rectangular but there are cylindrical keeps as well. A circular construction is better proofed against either missiles or mining.

The mighty, imposing 11th-century keep of Conisbrough, just west of Doncaster still soars impressively, rising incongruous from an industrial and suburban landscape. The curtain wall looks like it belongs somewhere else it is both crude and utilitarian. The towering beautifully ashlared keep is an odd one. Circular in plan, it has six projecting polygonal towers, set symmetrically.

Turrets can add strength and also provide additional chambers. Did lords live in their great towers? Possibly they did but not necessarily, that’s perhaps what distinguishes the keep from a hall-tower. This was the era when privacy was rarely a consideration in most homes. Those of high status might have had a solar to withdraw to when they needed confidentiality but they might well have slept somewhere far more public.

There are good examples of hall towers at Colchester and Castle Rising in Norfolk. These don’t rise above two stories and at 12th-century Colchester the tower sits squarely on the vaulted podium of the Temple of Claudius. A nice piece of flattery for the emperor but it didn’t impress Boudicca. It became one of her first, must-destroy targets.

Beautiful Castle Rising went up around 1140 with access through a fore-building then up a rather grand staircase to a first-floor vestibule and then into the great hall, which occupied one flank of the main block. Keeps, like mottes, were not built by the Romans, they are not an exercise in centralised statism so there’s no one-size-fits-all, they’re individual. They go up according to taste and the depths of the owner’s pocket.

A castle isn’t necessarily static, many evolve over time. A good example of a modest hall tower is Aydon in Northumberland, dramatically poised over the Cor Burn and close to the market town of Corbridge. This started life as essentially a civilian building but the fury of the border wars (which escalated in 1296) meant successive generations of knights, the De Reymes, had to steadily upgrade their defences, enclosing the courtyard then adding an extended curtain wall and corner tower.

Lordship is a primary function of feudalism but the individual baron or magnate enjoyed a pretty fair measure of autonomy. His castle defined his power and status, it didn’t just represent his place in the layer-cake: it was his...