CHAPTER 1

Sleepless Nights

‘Not for ourselves alone are we born.’

CICERO

Monday, 10 January 1921, Margate, England

The rain had stopped earlier in the night. The Revd David Railton MC put on his coat, hat, scarf and gloves, then left the vicarage through the front door. His leather-soled shoes crunched on the gravel driveway as he headed towards the road. He’d been awake for about an hour. Sleepless nights were a regular occurrence since his return from France. He found that once he was awake he couldn’t just lie there in bed waiting for sleep to return. He’d tried staring at shards of light from outside as they danced on the ceiling, or he’d listen to the metronomic ticking of the clock in the hallway, hoping it might have a hypnotic effect upon him. He’d even tried sitting by the fire, wrapped up in a blanket in front of the dying embers, staring at its ever-changing colours, praying that sleep might return. But over the past two years he’d discovered that the only thing that helped his nerves and kept his mind calm once he was awake was to walk.

In the dead of night, walking through the town, along the rail-tracks or on the promenade seemed to help. The exercise and fresh sea air cleared his mind. He spent the time thinking about sermons and speeches, even starting to compose a letter or two in his head. The more he thought of everyday tasks, the less time he had to think of the war. But try as he might, like most soldiers who had returned from the horrors of trench warfare, there was always something – a name, a place, or perhaps even a smell – something would bring it back. The air was sharp and crisp after the rain had passed; the clearing sky meant they might get a late frost before the sun rose. He pulled his scarf up over his mouth, then crossed the bridge over the rail-line and headed along St Peters Road.

By the early 1920s, expansion of Margate’s urban areas had pushed down to the rail-line next to College Road. In time, development would spill over into the countryside, eventually surrounding the vicarage with housing estates and a new hospital built in 1930. But at this time the vicarage sat on the edge of town, straddling the line between advancing urban sprawl and the Kent countryside.

Lit by white gas street lamps spaced about 50 yards apart, staggered on either side of St Peters Road, the darkened houses and narrow passageways that separated them cast a gloom that may have seemed a little forbidding to some. Street lighting had improved in the town, but because of its location on the coast during the war, restrictions had been in place. The ‘Defence of the Realm Act’ prohibited lights from the sea and bright lights in other parts of the town.1 Consequently, Margate was still badly lit after the sun went down. But David had spent many nights alone in total darkness trying to find his way back from the trenches. Margate’s darkened streets held no fear for him.

The year 1921 was a defining one for David Railton. It was the year when his pre-war life clashed with traumatic experiences in the trenches and shaped his future. In a letter to his wife, written from the harsh and bitter cold of a trench on the Ypres Salient in January 1917, he made a promise: ‘If God spares me I shall spend half my life in getting their rights for the men who fought out here.’2

Although he did this – arguably spending more than ‘half his life’ fighting for them – by the end of 1921, it looked like he was about to embark on a personal crusade to help all those in society who were not able to fend for themselves, not just those who’d fought in France.

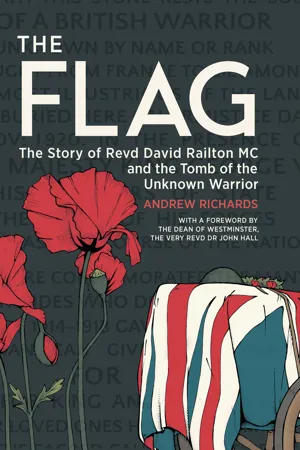

At first glance it looks like he had already achieved much. His idea to bring home an unknown comrade from France to be buried in Westminster Abbey had been achieved. The public reaction and outpouring of support was far more than he, the Dean of Westminster, the Prime Minister and even King George V could have expected. But outside the parish, despite being mentioned by The Times on 13 November 1920 as the ‘originator of the idea’,3 very few people knew of Railton or of the flag that was draped upon the coffin and now lying at the foot of the grave of the Unknown Warrior.

The year would start with a cold reality check for David and fellow Anglican clergymen up and down the country. The first Sunday service of the New Year was usually a time when congregations swelled with parishioners looking to start anew with a confirmed resolve of worship, wanting to see the New Year in with their family in their parish church. But the number of people sitting in the pews of churches up and down the length and breadth of Britain was low. Before the war, there had been a steady rise in numbers regularly attending Anglican churches. During the war, this trend continued. But after the Armistice in 1918, that rise had turned into a sharp decline. In 1914, two-parent families and their children lined up to hear a vicar’s weekly sermon, ready to sing their hearts out in praise of the Lord. Just a few years later, however, everything had changed. There were so many families with no males, the sons, husbands, and brothers all cut down in their prime. Some found solace in prayer, but for those left behind, times were hard. Without the returning men, many families had no breadwinner. Children were placed into orphanages while their mothers were forced to seek employment any way they could. Many ended up on the streets. For a soldier returning from the war who had managed to survive the slaughter, the Prime Minister’s ‘country fit for heroes to live in’ had quickly turned into a hell on Earth.

Discontent was everywhere; people seemed to no longer trust those in authority. Their generals had led them to victory, but at what cost? The government’s provision of pensions for families of soldiers killed was nowhere near adequate, and there wasn’t enough work for the hundreds of thousands of ex-servicemen who had given so much for their country. Against this backdrop David Railton was trusted, his Military Cross a testament to his dedication and bravery. His great oratorical skills meant there would ‘always be a queue when he preached’.4 But the widespread downturn in attendees across Britain was a clear sign that people had abandoned their church en masse.

Of all denominations, it seemed especially bad for Anglican Chaplains to the Forces (CF). It would be some years before the publication of Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That and Guy Chapman’s A Passionate Prodigality would leave a lasting stain on the reputation of Anglican chaplains; however, articles and controversial stories had already started to appear in local and national magazines and newspapers. Reports of churchmen in uniform doing anything to stay away from the front line, and soldiers hearing that padres had returned to England the day after their yearlong contracts ended, spread through the ranks of returning soldiers. The reputation of most Anglican clergymen – the minority who went to France and most who stayed within the safety of their parishes – had not gone untarnished.

David knew that time was a great healer, but it appeared to him that something integral which bound British society together had been lost, and it would take a great effort to get it back. The total destruction and wholesale slaughter of many hundreds of thousands of men had ripped open a wound so deep that David had found it difficult to heal – within the church, amongst his parishioners and, sometimes, even within himself. The losses brought about by war and parishioners’ unwillingness to attend church made him feel that throughout the country and within the Church of England, the country’s faith was starting to fail.

As if the war had not been bad enough, towards the end of the conflict in the spring of 1918 and throughout the first winter after the Armistice was signed, influenza killed millions of people across the globe. Now known to be the H1N1 flu virus, starting in birds then mutating through pigs kept close to the front line in Europe, it was believed to have spread from France. It eventually would claim 50–100 million lives worldwide. After losing sons in the trenches, parents were now losing their daughters at home. Many soldiers who had survived the slaughter of war were returning home to find their homes empty (repossessed by landlords) and their loved ones buried in the town’s graveyards. Even devout Christians must have wondered whether their God had forsaken them.

David had only been appointed vicar of the parish church of St John the Baptist in Margate three months earlier, so he was still very new to the job. At the end of the war, he returned as curate of St Mary and St Eanswythe Church in Folkestone in January 1919, the position he’d occupied before departing for France. But his war record, his association with the Unknown Warrior, and his previous work in Folkestone under a very influential clergyman, Canon P. F. Tindall, had brought his name into prominence within the Anglican Church.

He was inducted as vicar of Margate on 25 September 1920.5 Having previously lived in Margate on Gordon Road with his mother, younger brother and sister, he knew the town and was keen to return to it as vicar of St John’s when the Bishop offered him the position. He might have passed his mother’s three-story terraced house on one of his nocturnal wanderings, remembering his childhood there. His mother, who now lived just a short distance away in Broadstairs, left Margate when David’s youngest brother, Nathaniel, known to all as Gerry, had been ordained into the Church of England. David’s mother and sister would move back to Margate later that year, but living in Broadstairs she had already been close enough to help him through some very difficult times after he returned home. In a 1972 letter to Andrew Scott Railton, Mrs Kathleen Lockyer, a friend of the family, described what a huge support David’s mother was to him: ‘When David came back from France, his eyes damaged by gas and his mind in a turmoil, to take up the demanding parish of Margate, his mother grasped his state of mind and was able to soothe and strengthen him.’6

Apart from a string of debilitating illnesses that seemed to inflict the Railton children from time to time,7 Margate seems to have been a happy place for David as a child. He went to the Stanley House School8 and in the warmer months walked the short distance from the end of Gordon Road to the Queen’s Promenade and beach. He would spend hours playing with his younger brother and sister in the sand during the summer holidays, watching the fishing vessels come and go. These years filled him with happy memories. The only dark cloud in the blue sky of his childhood seemed to be the prolonged absence of his father.

George Scott Railton, the son of a Scottish Wesleyan Methodist minister and missionary, was one of the leading lights in the early days and first Commissioner of The Salvation Army. At the age of 15, after both of his parents died of cholera, he found himself jobless and homeless. His older brother, Lancelot, who also was a Methodist minister, found him work as a clerk at a London shipping firm. But his unwillingness to write lies on behalf of the company, even if they were just ‘white lies’, soon had him out of work again.

George’s upbringing was strict,9 so it is no surprise that at an early age teaching the gospel would run deep in his blood. After spending time in Morocco, he met William Booth and joined The Christian Mission, soon to be renamed The Salvation Army. After rising to the rank of General Secretary, then becoming The Salvation Army’s first Commissioner, he spent the rest of his life travelling around the world spreading the reach of The Salvation Army until his death in Germany in 1913 at age 64.

Even though Commissioner Railton had strongly objected to both David and his brother studying at O...